[ID:4847] Widows of Varanasi: The Ganga, the gallis and the grizzledIndia “Benaras is older than tradition, older even than legend and twice as old as both of them put together.” - Mark Twain

Along the banks of the holy Ganga, breathes the ancient city of Benaras, full of mysticism and spirituality. Legend has it that it is here that Lord Shiva's distressed mind attained peace after he had mistakenly beheaded Lord Brahma in a fight. Watching the setting sun against the rippling waters of the Ganga, it is hard to not believe the legend to be true.

Most of my dusks in the city were spent sitting by my window, watching life ebb by along with the holy waters of the river. On that particular day, however, I was more taken up by the banyan tree that grew alongside my lodge, right at the junction where the narrow gallli (alley) met the god-forsaken ghat. I sat there intently watching the sun’s rays play with the rugged dreadlocks of the tree, and that’s when I saw her. She was clad in a white shabby weave, head shaved, back bent like a bow from age, or maybe circumstances, who can tell. With a cane in her left hand and a bowl of alms in the right, she sat under the banyan tree shooing a swarm of flies that attacked her.

As she sat there fighting the swarm with her feeble hands, she was joined by another woman, no different than her. Together they launched a fiery battle on the flies, and finally managed to mark their own sweet spot under the tree. Only the sun, the tree and I were a witness to the indomitable spirit of the two women. What they could never defeat however, along with millions of others who shared their fate, were the stigmas of widowhood.

The two elderly women stayed there long after the sun went down, staring at my lodge and exchanging occasional words amongst themselves. I caught their phrases over the usual noises of the galli. Their story went thus.

The Laxmi Lodge wasn’t always this immaculately decorated cocoon that housed foreign guests. In fact a month back, it was just a nameless shelter for over a dozen aged widows who had come to Varanasi after their husband’s demise. Ostracized by society and abandoned by their families, these widows found shelter in the holy land of Shiva. It is here that they lived for more than fifty odd years, begging and chanting the lord’s name. But they know that they are a cursed lot. At seventy, these women have again been rendered homeless as the tourist population takes over the city. The dilapidated ashrams of the widows across the city are now being gradually converted to guest houses for the sake of profiteering. The aged have been rehabilitated to shabbier areas where the Ganga can no longer find them.

Widowhood in India has its own confounding history. The experience of a widow varies across cultures and time periods. There is no single idea of a widow; being a widow means diverse subjective experiences, varied inter personal and social implications and multiple changes in the life of women across diverse cultural settings. From pyre to poverty, the widows of Varanasi have faced it all.

In the dying light of the day and over the increasing galli noises, I could still hear the longing desires of the two women, loud and clear. What if we had continued to live here alongside the tourists, they wondered in silence. We could have offered them the love of a long-lost grandmother, made them delicacies, told them rare stories. Are those no longer sought after? We could have shown them our handiworks, catered to all their needs, pampered them with love. They too would have found a home away from home, would have got a glimpse of the sorrow in the city. We could have sung kirtans to drive away the gloom of morose evenings, sent them home with aachar for loved ones. We too could have relished a touch of the familial. Their stay could have funded our remaining days without the need to beg, or would that have been too much happiness than our fates can take? Are we too old now to dream again, too lost to ever be found, too invisible to ever be seen? Can the land of moksha not gift us a safe haven?

A safe haven. When faced with the most tumultuous storm, what more can a person ask for? But what does safe mean to the widows of Varanasi? It’s not surprising that after all these years, safe still means the same to these women : a family. A life of gloomy austerity could not kill their intense longing of being the mother of the house once again. If life had ever given a chance to these women, they would have asked for nothing more than a ball of wool and a pair of knitting needles to weave a sweater for their grandchildren.

An extended family has forever been a symbol of strength and security in Indian society. For adults and children alike, it’s the only space they yearn to come back to after the day’s battle is over. Whatever it might be, poverty, hunger or hopelessness, as long as you have your family, you can fight it all. It is a sociological structure that capitalizes on the strength of human bonds to guarantee people social security in all its forms. It’s not surprising at all that despite being shunned and ill-treated by their families, they still crave for nothing more than a touch of the familial.

For all these years the widows have lived as a community, supported each other and were supported by the people of Varanasi. There is strength in community, a sense of resilience. But it is only in a family setup that one gets the safe space to be truly vulnerable. Varanasi had given the widows a shelter when they were shunned, a place they could call home. The home thus far housed a community. Maybe now it can open its doors to that of a family.

May there now be no shabby ashrams for widows, but vibrant dharamshalas where they can reside alongside travelers from far flung regions. May it be a space where the widows get a peek into the great wide world outside, and in turn those who come to Varanasi, get a glimpse of India through the eyes of the aged. It can become a space where strangers cross boundaries of religion, region, age, gender and sect to form bonds that may never break. They may come and go, but return they shall. And that should be the essence of this place.

This place needs no ostentatious architecture. Just like a traditional Indian house with interconnected courtyards, it should be chaotic and share the same zing of the convoluted gallis. Each courtyard is perceived independently to house a unique experience that strives to breed intimacy through shared experiences. In an Indian household, rooms are but for furniture. Life, here, plays out under the open sky of the courtyards.

Imagine yourself to be a long lost traveler. As you reach the end of the narrow galli after carefully dodging through cow dung and frenzied hawkers, you chance upon the blue wooden door of the shabby chic haveli. The breeze over the Ganga, carrying the sharp sweetness of incense hits you, and that’s when you know you are back home.

Courtyard of Sweet Beginnings

As you push your way through the characteristic blue door, you chance upon the first courtyard of the household, the entrance courtyard. With a khatia in a corner, it is in the shade of this courtyard that the travelers will get the space to rest after tirelessly meandering through the never-ending gallis of Varanasi. It is here where the widows will first meet their new members. It is here where they will greet the travelers with a pail of water to clean up, and maybe later with a cup of piping hot Banarasi chai. This courtyard will bear witness to the blossoming of new family ties.

Courtyard of Cultures

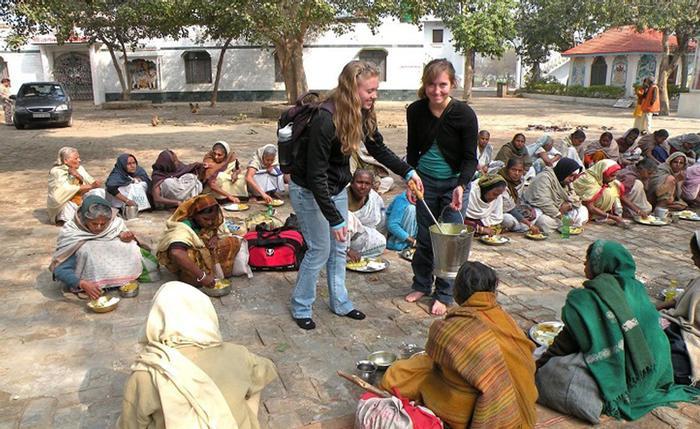

This courtyard will be but a melting pot for cultures, where traditions exchange hands. On one side you get to spot a widowed Amma with a toothless grin, as she learns how to play the banjo from a seemingly Caucasian cowboy. At the same time on the other side of the courtyard, a group of giggly Asian girls are learning from the widows how to drape the saree the Bengali way or the Maharashtrian style, whatever may be the mood of the day.

Courtyard of Cuisines

An offshoot from here, maybe lead you to the Courtyard of Cuisines, as where gourmet secrets from around the world get entangled with the traditional recipes of the land to create unheard of flavor combinations. As the afternoon dwindles, you watch this extended family gather up for a meal. You can’t help but smile as you watch the elderly coax the younger ones to eat up an extra morsel.

Courtyard of Storytelling

Here again will be a courtyard designed as the storehouse of myriad stories. Seated in the center of the courtyard on a rugged mat, you will chance upon two groups in deep conversation. One group clad in white, the other dressed in eclectic colors. Drenched in the mellow light of dusk, they will take turns to share their life stories, some joyful, some humorous, some simply silly at heart. It is in this courtyard that you will get to experience the lucid blissfulness of storytelling.

Courtyard of Melody

Then a courtyard to drive away the ghost of gloomy evenings. With a shrine adjacent to it, it is here that one can join the widows as they sing soulful kirtans, chant prayers and perform the evening aarti.

The River and the Ghat

All journeys in Varanasi lead to that one place - the river and the ghat. It doesn’t matter how labyrinthine the gallis become, the traveler here knows it will only end on the banks of the Ganga. As the evening gives way to darker nights, the family will emerge from the narrow backside doorway leading to the ghat. It is here that the weary travelers and the widows share moments of silence, experiencing their sorrows diminish and their joys double as the Ganga ebbs by. With songs of boatmen playing in the background, it is this one moment of serenity that holds the power to tie them as one in an unbreakable family bond.

You say it is hard for two strangers to become family in an instance? Well, I have always believed that magic happens and sometimes architecture too can be the magician. It is often the simplest most lucid design that holds the greatest power to foster such magic.

Architects have proved that time and again. When Ar. Madhav Naik was asked to design a rehabilitation center for the elders who were rendered homeless by the tsunami, he knew the challenge in front of him was to architecturally recreate the ethos and social milieu of their earlier life. It is only in such a setting that the elders will truly be able to revive from the trauma and the loss. He then set out to design an exemplary elder’s village with interactive open spaces and hutments clustered around a courtyard. Built in true vernacular style with local materials, intermittent livestock shelters, herbal gardens, and dairy farms, the elders never feel out of place here. They spend their day rearing cattle, growing crops, creating decorative floral pieces, everything they would do back home.Their evenings end by the lotus pond or the Tamaraikulum, as the village is called. Ar. Naik showed that as we design for the elderly, we should strive to understand the essence of the life the elders have lost and then consciously incorporate that in our design. That in itself will ensure that the elders never experience a sense of uprootedness in a supposedly new setting. The success of his design is apparent as one watches the elders engage in the various activities and move around the village as if it were their own. One can feel the sense of freedom they experience from their each stride.

With aging comes diverse needs. As the body deteriorates, one needs greater assistance to get through life. But in essence, what the elders really yearn for is to hold on to the life that is fast fleeing, to hang on to older times. As architects, that is the bare sensibility with which we need to design for the elder’s of our community. At each step our design should strive to eradicate the constant fear of loss that lingers in their psyche - loss of health, loss of family, loss of livelihood, loss of life.

And what can be said of those who had lost it all eons ago in the flaming blaze of their husband's pyre? It’s high time the land of moksha gifts them a safe haven.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |