[ID:4084] Less can be More: Towards an Architecture of HopeIndia A City / This is Delhi, My Friend

The sky was a cloudless grey, and morning mists were floating thick. The trees were bare, with their few leaves a shrivelled olive. It was a chilly winter morning in Delhi. I was on my way to what used to be the stout and stately Delhi residence of the Maharajah of Travancore, now a disused mansion. I was less than a hundred metres away, when I sighted three men ahead engaged in a spirited conversation over a sack-like object. They were drawing stares from all around. As I neared them, their voices cleared. The sack was a homeless man who had frozen to death in his sleep. One of them remarked in Hindi, ‘ye Dilli hai, mere yaar’. This is Delhi, my friend.

Delhi’s head-roasting summers and soul-sucking winters are responsible for hundreds of deaths every year, and there appears to be no end in sight. Every year, more migrants march to this city than perhaps any other city in the world, while temperatures dip and soar today more than they ever have. The city cannot sustain so many even under favourable circumstances. What happens now?

Enter air pollution. In the November of 2019, the city disappeared in an acrid haze. We had been accustomed to distant monuments disappearing for a few hours. But now, that familiar grey melancholy had consumed the entire city. Vehicles were crashing into each other, jamming roads with rows of wreck. Our eyes were burning. We were coughing like our throats were being hammered. A public health emergency was declared, and everyone was asked to stay indoors.

As if everyone had an indoors!

And last year, of course, the pandemic took hold. Through most of the year, Delhi was leading the country in infection and death rates. Thankfully, we were well-prepared on one front: the city’s chronic pollution problem had already groomed us into living behind masks.

But once again, everyone was asked to stay indoors. This was almost a joke now.

Delhi’s homeless and poorly sheltered are exposed to sun and rain, but that is just the beginning of their problems. They do not have access to basic servies such as water and sanitation, compromising their health. When anything goes wrong in the city, whether it is because of the annual pollution spike or a global pandemic, these people are the worst hit – physiologically, emotionally, and economically. For all these reasons, children born in such environments cannot expect much to do well in school, which is generally their only way out. Finally, such conditions also markedly accentuate prejudiced priorities, causing particular distress to women and girls, as a 2015 essay (ID 1451) notes. Then there are even more disadvantaged people, such as the differently abled and the LGBTQ.

This situation is a cornucopia of problems. But it is also symptomatic of deeper issues such as urban poverty, rural unemployment, and social and political deprivation. Such is the extent and complexity of this web that it is no wonder Anthony Schuman writes in his introductory essay for the 2015 Essay Prize competition that architecture alone is incapable of transforming lives in low-income communities.

Nevertheless, the architect can confront and grapple with these issues. They must, because if not, the city becomes an unjust place, hospitable only to a few. If an architect does not contest this, they are essentially renouncing their agency to aid society’s elite in their consolidation and assertion of wealth and power, perhaps in the hope that they too can be a part of this elite. I know which kind of architect I wish to be.

How do I undertake this mission? How could I, an architect to-be in Delhi, confront homelessness, inadequate shelter, poverty, and deprivation? This is what the essay sets out to answer.

A Colony / The Constraints in Delhi

In his 2016 essay (ID 1641), Ayushman Kedia writes about his visit to Delhi’s infamous Kathputli Colony. Over the past 50 years, this locality has become home to close to a thousand painters, sculptors, puppeteers, and musicians. However, not everyone considers it their home. It is what some refer to as a ‘squatter settlement’, where people are condemned to live with the sword of demolition constantly hanging over their necks. Making his way through it, Kedia describes it as a ‘hellish sight’.

Thirty years before him, a young architect by the name of Revathi Kamath had wanted to change this. She carefully documented the entire settlement, including every unit, and sat down with the residents to design a new masterplan that catered their various specific spatial and social needs. The project was called Anandgram, Hindi for ‘village of joy’.

Kamath had involved the Colony’s residents in her design process and put forth what Kedia finds to be a sensitively thought-out proposal. However, ‘participatory planning’ was yet to become a buzzword. The proposal conflicted with the interests of local authorities, who were occupied with dreams of flyovers and metro stations. The village of joy could wait.

Since then, the Colony’s resident population has grown. Kedia notes that when the government has responded to their plight, they have chosen to do so by deploying developers to build faceless multi-storeyed blocks that pay no heed to the residents’ social, cultural, or individual needs – a housing response that has repeatedly proven to not work.

Consequently, it is quite likely that the children of Ghanshyamji Bhopa – the Colony resident whom Kedia had met in his cold, damp house – are worse off than he was. What those conditions must be, I cannot imagine.

This story illustrates only one of the many possible ends an architect’s proposal could meet in Delhi. Alternatively, a public body could be most sympathetic, but lack the financial resources required. It is even possible that the concerned authorities are able and willing to help, but a nearby community decides to raise objections. Whatever be the case, this is what Delhi is like – resources are tight, problems many, and interests conflicted.

A House / The Architect’s Place in Society

The Architect, of course, seems particularly disadvantaged here. After all, in the words of Nathan Koren, winner of the 2000 Essay Prize, the architect is at the bottom of the food chain, constrained by developers, planners, and society’s many institutional and infrastructural systems. So much so, that this has compelled Koren to move away from architectural practice over the years.

However, I believe there is another way to look at this. In his recent address to the School of Planning and Architecture at Bhopal, Benjamin Clavan recounts his experience of retrofitting a house for a young, struggling lawyer who had been partially blinded by a surgical accident and could only differentiate between shapes and bold colours. He remarks that as an architect, he would have loved to pull down the entire house and rebuild a perfectly accessible one. But neither did she have the budget for it, nor did she want a radically new design. She just wanted a ‘normal’ place that she could use without running into walls.

In response, Clavan used his interest in colour to sign and pattern the walls so that the lawyer could read the spaces of her house. He recollects that when she finally saw the results, she was overcome with emotion. At last, she could see her home.

Clavan’s work was of a truly small scale. Not only did he work with an individual house, but he also altered it only minimally. But all the same, his work made a profound difference in the life of an individual. It might not have transformed a community, but did it not make a worthy contribution?

Having spent all my life in India, I have often found myself urged by the scale of its populace and problems to imagine grandiose solutions. Therefore, I sympathise with those who wish architects were top-down agents of change, capable of rebuilding entire cities.

At the same time, I do not think that that is the architect’s role in society. A House for Someone Unlike Me is a 1984 film about the Universal Design course then developed at the University of California, Berkeley. In the film, we see students discussing their design of a house – or having a ‘crit’ session, as we call it – with studio faculty and visiting disability consultants. While the film itself is about the pedagogy of Universal Design, something else about it struck me – the student was, at once, working with the individuality of the imagined residents of the house and that of the disability consultants. Beyond this, they were perhaps working with the individuality of the studio faculty too. The Universal Design course was, in fact, purposely designed so that students grapple with the uniqueness of disabled users, rather than work with them through generic abstractions.

It seems to me that the spirit of the architect’s education and training – of the college studio, boutique practice, and beyond – is deeply individual. It is grounded in one-to-one interactions. In a good architect, this must cultivate a special sensitivity to individuality and uniqueness. A sensitivity that society needs, because no matter how mountainous its problems are, they are ultimately experienced by individuals.

I do not argue that architects must limit themselves to working with individuals or at small scales. On the contrary. But I think whatever scale an architect works at, their unique capacity lies in their ability to cherish the individuality of those they work for. To the planner and the bureaucrat, communities and people are generally abstractions – figures and graphs. To operate at their scales, perhaps one needs to work with abstractions. The architect could, in turn, be the professional with their ear to the ground, understanding and working with communities directly and tacitly.

Half a House / Working with Constraints

This defines a unique scope for the architect – one with both opportunities and constraints. How could an architectural practice dedicated to improving local communities operate within the constraints of both Delhi and the profession itself?

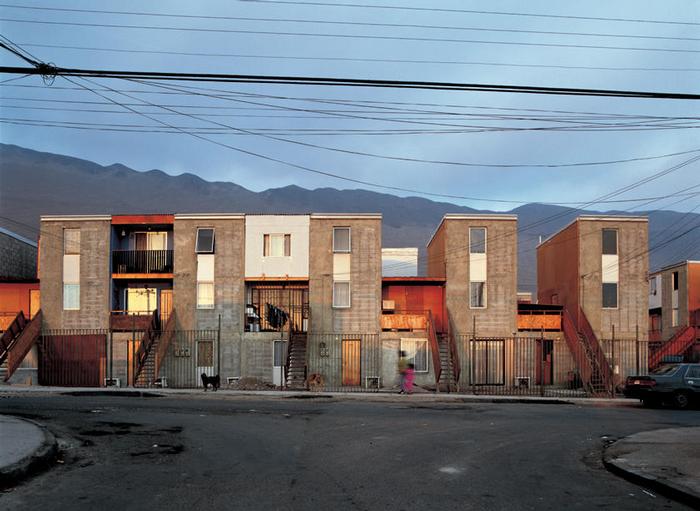

The work of architectural firm Elemental in Chile suggests a possibility. Consider the Quinta Monroy Housing in Iquique, for example, where the firm designed a variation of the traditional row house which was half unbuilt and barely fitted. Doing so enabled them to make a larger area available to each household within the project’s miniscule budget. The idea was that these houses could be expanded gradually and customised according to the needs of individual households, rendering them more liveable in the long term.

Elemental’s approach to social housing was fundamentally different from that of Revathi Kamath’s. For the former, feasibility seems to have been a key constraint right from the beginning of the design process. Kamath seems to have put aside the question of execution while designing, while Elemental considered it imperative that something be constructed. To quote Small Scale, Big Change, a 2011 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Quinta Monroy Housing was ‘radically pragmatic’.

The exhibition presented, along with this project, 10 other projects representative of a new wave of architects contributing to society. It remarked that these projects, in their spirit, were similar to the grand utopian visions of the twentieth century. But unlike the latter, they did not seek to disrupt from the top-down. Rather, they sought to contribute from the bottom-up. They were ‘acupunctural’, working at small scales but having positive effects at a much larger level.

If the architect is understood to be a professional working directly and intimately with individuals and communities, I cannot imagine a more meaningful way in which they could contribute to society.

A Platform / Towards an Architecture of Hope

Through the eyes of an architect seeking to do good, this makes clear sense. But how much could society benefit from modest architectural interventions?

To answer this, we will turn to Dhaka, Delhi’s friendly neighbourhood capital. Karail is Dhaka’s largest slum, and in the words of a 2015 essay (ID 1417), it is ‘shamelessly’ separated from the posh area of Gulshan by a lake. The essay traces the work of an architect called Hasibul Kabir, who decided to engage with the community by shifting his life there.

Kabir believed that as a settlement, Karail had all the social and community amenities an urban environment needs to have. However, it was physically in despair. In response, he began growing flowering plants and vegetables around his house. These plants attracted the neighbourhood’s children, who picked up their seeds and playfully sprinkled them across the settlement. Soon, flowers in pink and yellow began to blossom in a settlement where perhaps life’s complex concerns had long overridden desires of simpler pleasures.

As more children started to appear, Kabir realised that they needed a better space to meet and play in. He took the help of a few others to build a deck-like platform from reused bamboo that partly floated on the lake. A small portion of the platform was covered with a thatched roof, while the rest of it was open to sky. Close by, Kabir also started a small library, where children could gather to read and learn.

By all measures, this was a modest architectural intervention. But it made an extraordinary difference in the lives of the people of Karail. It beautifully fulfilled their need for a space where their children could play and learn. Simultaneously, it also injected positivity into the entire community. That they were deprived of some things did not have to mean that they had to resign to a life of lack. Tithi, a thirteen-year-old girl, aptly named the space ‘Ashar Macha’, or ‘Platform of Hope’.

The platform did not overhaul living conditions in the slum. But it made a real difference in a way that perhaps only sensitive architecture could have. Shelter might have been architecture’s primordial purpose, but today, architecture is much more than that. As thinking beings, the conceptual is as real to us as the physical. Therefore, this is perhaps architecture’s most meaningful and profound capacity today – the ability to fulfil tangible needs to the extent feasible, while fortifying and inspiring its community to have faith in a better tomorrow. This is the kind of architecture I wish to dedicate myself to.

Delhi is a city where homelessness and poverty are as everyday as decadence and ostentatious displays of wealth. Here, an architectural practice must operate within the constraints of the city’s power structures and the profession itself. Therefore, if physical conditions can be transformed to elevate a community, then as architects, we could zealously undertake this endeavour. But if not, let us ameliorate life in the community to the extent possible, and give unto them something they can hold on to – a promise that things will change for the better. Someday, even if not today. Into the dark waters of despair, let us shine a beacon of hope.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |