[ID:3452] What are changes are for? Stories and realities in Ecuador that architecture revealsEcuador Nothing has greater potential to reshape our lives as the huge challenges, today, our generation will have to transform itself to overcome climate change.

Nevertheless, in developing countries as Ecuador our socio-economic conditions have limited our governments to only focus on overcoming the most visible issues like poverty, violence and the lack of social services, then, problems like climate change are something that they leave the developed countries to solve. We still don’t possess a true knowledge -in scientific terms- of how our environments and societies work and how they are affected, research has just started to have significance in the last decade and it still lacks support. Moreover, the indifference to our culture -profoundly related to indigenous civilizations- is drifting us away from our collective identity. Sadly, we need external validation to appreciate our culture. This has produced a scarcity of confidence to believe in the potential of our ideas to propose solutions for ourselves.

Since architecture is the tangible expression of our society, in Ecuador it expresses those issues. Hence, it is not common yet to have local examples of recent architecture built under sustainable and resilient terms that responds to our own realities and necessities. Our conditions have limited architects just to fulfill functional and economic needs but leaving the climatic comfort and ecological requirements behind even when they are strongly linked to the community welfare. So, I will state my beliefs through the stories of two edifications: the museum of Agua Blanca (Machalilla) and the Seymour de Baltra Ecological Airport (Galápagos).

The museum of Agua Blanca

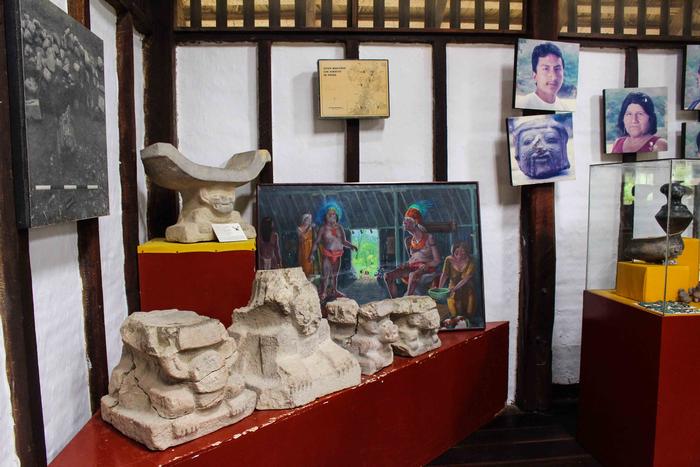

This building represents the history of a small community located in the northwestern Ecuadorian coasts, saved when its members awarded that the protection of its culture and environment were the key to its survival. The ancestors of Agua Blanca are millenary cultures: Valdivia, Machalilla, and Manteña, that disappeared after colonization. In 1970, after many years of culture and history loss, the government declared their territory a National Park due to the presence of tropical dry forests -considered as endangered ecosystems- and forced them to leave since their presence was considered as a threat for the ecosystem. However, in 1978, the Scottish archeologist, Colin McEwan, found rests of the ancient cultures and started a project. As he explains, his team made an effort to pioneer an integrated approach to culture, ecology, and subsistence, he beleived that local communities have a vital role to play in protecting the environment and managing cultural resources wisely (McEwan, Hudson & Silva, 2000). The starting point to make this real was to build a museum in-site, a structure that would not only store archeological artifacts but would serve as a reference for the community to see differently.

McEwan, Silva, and Hudson encouraged the community to build the communal museum and soon they gained collective support and commitment. In 1990, under the direction of the foreign architect, Chris Hudson, they built the structure using local materials and traditional construction techniques creating a structure suitable for the village landscape and the dry tropical climate that characterizes this zone. Furthermore, by using local materials and teamwork they accommodated the construction to the economic limitations. The building is composed of timber, split bamboo, palm thatch, cobbles and quincha (a bamboo and earth wall structure) that were extracted from the woods and the close river. The structure rises on piles that help to avoid humidity in certain months, it also counts on cross ventilation that assures the entrance of fresh air, jointly to the quincha walls and the thatch palm roof, they keep interior thermal comfort. The structure´s lightness and flexibility make the building resistant to the frequent seismic movements in this region.

After the museum construction, Agua Blanca realized their potential as the heirs of a millenary culture to protect their territory that was about to get lost. They reclaimed its land- that today is completely shared- and started to practice community-based tourism, which reactivated the community´s economy. They became the woods guardians. Today, they use its resources only for the benefit of community improvements. Agua Blanca is an example for other communities and maybe the only one that represents the traditional coastal regions in Ecuador.

McEwan and Hudson explain that the museum helped to validate building skills and techniques that were on the edge of being lost. In fact, the next public buildings such as a communal restaurant and a church were built with the same traditional techniques, which were the most appropriate ways to build to keep the local natural and cultural landscape and to protect people from the high temperatures, as well as the earthquakes threats. Indeed, these structures proved its resistance to the earthquake that Ecuador faced in 2016. The touristic guides, Plinion and Stalin -who spend long journeys in the museum- feel protected from the heat, they have never used a fan, air conditioning or any other expensive technology to have a comfortable experience there. They also reveal that it is not easy to maintain traditional structures under the climate conditions they deal with but since this museum contributes to everyone´s economy is possible to do it collectively.

However, the community has been facing new challenges in the last years. One of them is the restriction of the use of local materials by the governmental authorities in charge of the park; yet, without proposing any project that allows the community to have a reforestation plan to use part of the resources responsibly. Besides, the changes that the globalized world has brought, many people in Agua Blanca has started to build with industrialized materials, whose ecological footprint may be dangerous in these environments.

The Galápagos airport

Galápagos, an archipelago conformed by 19 isles is a unique place; its volcanic origin, geographical isolation, and climate conditions have brought to life endemic species and beautiful landscapes. Over the years, these islands have been a home for pirates, scientists, American military bases, prisoners, and an Ecuadorian community since it was officially added to the country in 1832; yet, it started to populate significantly in the ´80s. The UNESCO declared these islands a Natural World Heritage Site in 1978, a Biosphere Reserve in 1985 and an endangered Natural Heritage Site from 2007 to 2010. The main economic activity in Galápagos is tourism and today, animals, plants, and humans depend on the conservation of the island’s fragile conditions.

After many years of exhaustive tourism, Galápagos needed a bigger airport; consequently, in 2012 a new terminal was built to improve the tourists and the community experience. It was imperative for the authorities to invest in a sustainable structure with low environmental impact. A foreign enterprise was contracted, Corporación America together with the AFS Arquitectos studio. The initial purpose was to build a structure capable to get international certifications that guarantee its sustainability. They built the first ecological airport in South America and the Caribbean.

The building materials were reused from the old airport and the rests of an old oil-rich located in Ecuadorian coasts which reduced the waste that causes degradation of natural atmospheres. This airport counts on natural ventilation and illumination. The energy that the airport requires comes from 360 solar panels and three Eolic turbines. In respect of the water consumption, the airport counts on a system that recovers the gray water and reuses, so that, they reduce 80% the use of potable water. In addition, the builders planted the endemic flora and take care of the fauna, for instance, the workers are prepared to hold iguanas from its tails and take them away from the landing strips every time they see one crossing when a plane is circulating.

All those characteristics made possible for this building to obtain a golden LEED certification, granted by the US Green Building Council, that awards to highly efficient green buildings. Wendy, a member of the staff affirms that the major goal is to keep its position as a carbon neutral building every year. The people in charge of the construction assumes it was possible to accomplish an energy efficient project despite it was executed 1000km away from the continent; therefore, it is irresponsible not to do it in more accessible locations. Sadly, the investments for projects like this would be only possible in places with global attention as Galápagos.

Regarding the perceptions of the dwellers, when I asked them about the airport, they showed disappointment. Even though Galápagos doesn’t count on native civilizations, the population who live there for decades feel an enormous ecological responsibility. People like Giovanna and Cesar, a touristic guide and a taxi driver, believe that the airport was built under interests that were not necessarily linked to the community welfare. They think that a project like this could have been an opportunity to enhance the local economy by giving the locals chances to participate but this never happened. Furthermore, despite the high airport charge that visitors pay, few portions are invested in the community. Galápagos count on an ecological airport that got international recognition with users who whiteness thermal comfort, but such an investment could have had such a bigger impact. For instance, the locals could have learned techniques to build their future buildings in a more sustainable way. Moreover, some of the money that they collected from airport taxes could be used to projects that supply houses of any kind of clean energy systems because that could benefit enormously to reduce the impact that populations living in these environments cause, as the local Institute of Efficient and Renewable energy discusses.

The lessons

As it was explained, both communities have similar conditions, they develop in very fragile environments where its social and economic survival depends on its conservation. In both cases, the negative consequences of climate change would be devastating. Each of them has important buildings that reveal their realities. On the one side, Galápagos, a place internationally recognized where any kind of public investment would be visible and claimed. On the other side, Agua Blanca, a community that takes charge of its territory with their own resources, a lack of government support and environmental solutions. Both buildings, the museum, and the airport leave very clear lessons on how to reach resilience and what the obstacles are.

The Agua Blanca museum is a result of architecture based on traditional Knowledge, I consider it as evidence of what the architects of the past, ancient communities, have done to cope with the climate changes they have experienced. Their legacy is a laboratory of centuries of responses to environmental change explicit in their architecture, agriculture systems, and lifestyles. One of the most important lessons they showed us is how to truly belong to nature and to a culture. Almost every ancient civilization on Earth possessed deep bonds between nature and humanity -a oneness- through that connection and collective identity, the adaptation to natural and inevitable changes comes instinctively.

However, the traditional structures in Ecuador are in decay. They tend to represent the housing of the poor. As soon as the economic situation of a family improves, they change their houses to industrialized materials. Despite the benefits of building with natural and local materials, many communities have other perspectives on development, they want their houses to look like the ones they see on the internet and TV. We lack real examples that show new architecture that fits our current realities based on the local. In Agua Blanca, they experienced something different and that’s why they were able to preserve some of their traditional values. But since the construction of the museum -and the way that it was built- was promoted by foreign people, it raises a question: In developing countries, do we need only external validation to value what we have as a culture?

On the other hand, the Seymour de Baltra Ecological Airport is a great example of a building that reduces the negative impacts that such a big structure would cause by recycling and using clean energy systems. Yet, one of the pillars of sustainable development was neglected, the social one. Here is where I highlight that the link between architecture and climate resilience lays on building under environmental and socio-cultural requirements because to overcome the negative effects of climate change it is essential an empowered community willing to work collectively and capable of self-organization. Architecture can endure these values just like happened in Agua Blanca, by making the community part of the project and by enhancing cultural roots. This is the first rule for a resilient design that I have identified.

The problem in my country is that instead of understanding ourselves we focus on copying and adapting other realities to our nation. In order to reach an integral project is important to understand deeply our contexts, how the environment performs, what people really need, how it could impact their lifestyles. Hence, the second rule I have recognized is that design should go hand in hand with science, not only of technological advances but also of the sciences that help us understand our societies and environments. In Ecuador, is important to start researching our reality. Many of the new technologies were not intended for our socioeconomic limitations, but through cooperative research, we can think how to make them work for ourselves, how to make them reachable for everyone, and maybe we can find simpler solutions, more suitable for us.

Final thoughts

What is to be resilient? Is to be unchangeable? Is to feel powerful that the biggest changes wouldn’t affect us? Somehow resilient architecture is ironic because the term itself means to be adaptable but we build edifications that are supposed to remain the same after the change. But the answer is to evolve, that is what changes are for. To overcome this huge challenge called climate change, we need to transform the way we act, the way we do things every day, the way we feel about our surroundings -nature- and ourselves. As future designers, we have a key role because we can transform the way others inhabit to make them feel and do differently, to consume less. to share more and to change habits. That is the third designing rule I propose. Malafouris states “Humans… build to shelter and protect but… they also build to define the ontological conditions and limits of selfhood. In many ways, then, the boundaries of the forms we built become the limits of our consciousness. And if we also accept that a being’s mental states can never extend beyond those boundaries, then setting the right kind of limits is essential for who we are” Perhaps climate change is a stage that demands us to become more human beings than human doers.

References

Bené, C., Godfrey, W., Newsham, A., Davies, M. (2012). Resilience: New Utopia or New Tyranny? Reflection about the Potentials and Limits of the Concept of Resilience in Relation to Vulnerability Reduction Programmes. IDS Working Papers, 2012(405), 1-61. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.2040-0209.2012.00405.x

Braw, E. (2016, March 27). Climate change is transforming the way we build. Retrieved from https://www.raconteur.net/business-innovation/climate-change-is-transforming-the-way-we-build

Gómez-Baggethun, E., Reyes-García, V., Olsson, P., & Montes, C. (2012). Traditional ecological knowledge and community resilience to environmental extremes: a case study in Doñana, SW Spain. Global Environmental Change, 22(3), 640 650.

Malafouris, L. (2013). How things shape the mind. MIT Press.

McEwan, C., Silva, M. I., & Hudson, C. (2000). Usando el pasado para forjar el futuro: génesis del museo y centro cultural de la comunidad de Agua Blanca. Espacios en disputa: el turismo en Ecuador, 99.

Climate change: resilience and adaptability. Promoting open dialogue and best practice on climate change. Retrieved from https://www.arup.com/perspectives/climate-change-resilience-and-adaptability

Ecogal S.A. Primer Aeropuerto ecológico del mundo. Retrieved from https://www.ecogal.aero/construccion-sustentable

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |