[ID:2447] Blurring boundariesIndia Mumbai. Years before it became what it is today, up until the 16th century, it was fragments of land scattered in the Arabian sea, inhabited by the indigenous koli fishing colonies. A handful of people living simple lives unaware of the prospect of the land they were sitting on. For Mumbai’s unique geographical location and also having one of the best natural harbors in the world, slowly attracted traders from all across the world and India, and Mumbai became a port.

The city achieved a new identity, that of a trade town and trade became a gateway to the subsequent developments in the city which have now led to the emergence of Mumbai as financial capital of the country.

Trade, Commerce, Industry, Finance. One may think that is all that defines this city. A look at the recently developing architecture ascertains this picture. The skyline of the city is framed with buildings only going higher and higher. But this picture is incomplete.

These opportunities, also brought to Mumbai in enormous magnitudes its most valuable commodity, people. Waves of migration brought different communities and classes of people to the city. Some came to dominate the financial potential, some came for a small share – to make a comfortable living, some came attracted by the dizzying big city lights, and some came to earn two meals a day.

They brought with them their cultures, their habits, all adjusted to make place for the other, in a city already scarce for space. India is a diverse country with more than a hundred indigenous identities and only one city has them all coexisting with each other. Not marked and separate but rather interwoven and indispensable to each other, making Mumbai a melting pot of culture and unique in a way no other city in the country can imitate.

Every stage of development in the city in linked with many communities and stakeholders, but their presence is vanishing in the single minded approach to development. Apart from being a koli fishing community, to a colonized city, to an industrial city and now a city of skycrapers; Mumbai also has manifold distinctions and a highly diverse population.

“The thing about Mumbai is you go five yards and all of human existence is revealed. It's an incredible cavalcade of life, and I love that.” - Julian Sands

Let us begin our discovery of Mumbai’s hidden identities by going back to the very beginning. The time before it all began, a simple time. When Mumbai was an archipelago of seven islands, inhabited by koli fishing colonies. The invaders came and converted these native people to Christianity, and were henceforth called the East Indians.

That layer of the city only exists in fragments, one of them being Khotachiwadi, a heritage village now located in the midst of Girgaon, a prime residential land. I get off the main road and continue in the alley, I can see many buildings and skyscrapers in their various stages of completion around me and in the distance. It is strange to me how it seems sensible to people to keep densifying an already dense old city area.

As I take the narrow winding lane to the village, the buzzing traffic noises hush down, the construction noises are lulled and without a warning I have travelled back 200 years. Khotachiwadi literally means Khot’s village and the history is that a man named Khot sold these homes to the East Indian Catholic families.

The houses are two and three storied wooden structures of old Konkan and Portugese style architecture. Some with chipped old paint, some freshly painted but all are brightly colored. If not, then it would be difficult to recognize where one house ended and the other began. The doors, windows, edgings are intricate wooden carvings and designs. Every house has a distinct character, over the years the additions and renovations have been thoughtfully done. The old and the new merge as one.

The ordinary Koli house comprises a verandah (oli) used for repairing nets or the reception of visitors, a sitting-room (angan) used by the women for their household work, a kitchen, a central apartment, a bed-room, a god’s room (devaghar), and a detached bath-room.

The houses have large open front verandah, a back courtyard and an external staircase to the above storey. Some elderly citizens are sipping tea in their verandah or reading the newspaper, children are playing football in the streets – there is no ground. There is a Catholic chapel with stone benches and the walls are covered in street art. The pace is leisurely, the people are relaxed, most of them are descendants of the original inhabitants of Bombay.

The homes are close together, the streets are narrow, it seems as though the whole village is huddling together, trying to stay united in the face of some impending danger. And the danger we greeted before reaching the village, the conversion of these areas into concrete jungles. The village originally had 65 homes and have now dwindled to a measly 28. As I try to capture the essence of the place I realize I am standing at the precipice of the earliest fishing villages and colonization. The future of the village looks to be uncertain and carrying the fear in my heart, I leave Khotachiwadi.

Travelling from the South of Mumbai to the central part of Mumbai, I also travelled in time to the era which came post colonization in the history of the city, the time of Industrial revolution. In the nineteenth century, cotton textile mills were set up in an area called Girangaon which literally means mill village. Bombay was called Manchester of the East and the cotton textile industry contributed significantly to the prosperity and growth of Bombay and the conversion of the city to a major Industrial metropolis.

The mills brought in masses of people to the city, looking for jobs. Synonymous with the mills are the mill workers housing called as chawls. Cost effective housing for the poor mill workers, they were built close to the industries. Half a century ago, with over 52 mills in less than a three mile radius, Girangaon was a crowded, lively and dynamic hub.

Today the Industries are shut but homes of the mill workers still remain standing and their lives go on. Located in the heart of the city, Girangaon, now has a skyline of the tallest and most luxurious residential development in Mumbai; yet if one turns their gaze a little below, one will realize it is built on the ashes of the bygone mill lands.

A ghost town, the air of Girangaon is buzzing with mixed energies. Earlier it housed the poorest and most depraved sections of society, the working class and now it houses the wealthiest sections of society. The chawls sit at the edges of the mammoth buildings and are few and far in between.

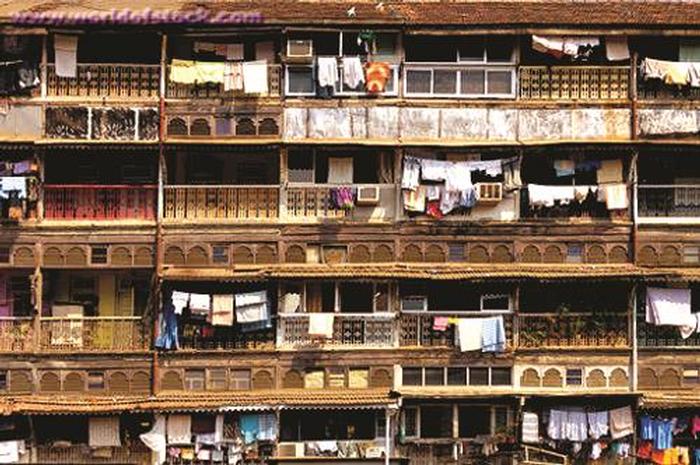

Chawls have a characteristic layout plan. They are typically 4 to 5 stories tall, with between 8 and 16 tenements on each floor. Each tenement is a single multi-purpose room. A central staircase services the building and gives access to a long passage which runs the length of each floor. The defining feature of chawl architecture is that all the tenements are ranged on one side of the passage, leaving the other side open to the sky and serves as a balcony.

Chawls are simple, plain buildings, they are not distinct from one another. They are social housing and hence are dense and compact. They even lack basic facilities and sometimes are unsanitary. The people have no privacy and families have barely sufficient space for living in their one room tenement. Yet it is the building type most fascinating to me out of any other in Mumbai. We keep believing that good architecture has the power to change the lives of people. Yet the chawls are a remarkable example of how people make a dynamic life for themselves not because of their architecture but in spite of it.

While chawls do not allow for a comfortable life in the miniscule one room tenements, people have a made a life for themselves out of any and every space possible. The central courtyard where 3 to 4 chawls are built around is the venue for celebrations, weddings, sports, festivals, fairs and meetings; the balconies adjacent to the rooms are where people spill out and engage with one another from morning to night; the staircases are where people from different floors interact; the common toilets, sidewalks, benches under trees, boundary edges, shop fronts and street corners became social gathering spaces.

The population of the mill workers is diverse and includes people from all castes and religion. But this unique living situation has fostered strong ties and bond between families. Each family is knit to the other like its very own. Their happiness, difficulties, celebrations are shared and their hearts beat as one. Girangaon is poor, dense and illiterate, yet it is filled with talent in arts, laughter, love and an unparalleled community life.

Uncovering each layer of the city, exploring the architecture of different communities, I am transported to another century, another world. Every community I went to see, I had the modern buildings looming over me and their future. And now I turn my attention to the only predominant community which shapes the architecture of the city, the community of the wealthy. This kind of architecture is the very antithesis of what I believe to be for community and culture.

The massive high rises are a dazzling and exciting affair. The average Mumbaikar sucked into believing that the cityscape is changing for the better. The intimidating towers are a symbol of proof that indeed we are on our way away from the poor, developing nation that we once were. Or are we?

India is urbanizing at an unprecedented pace, the cities are where the future of the country is. While this is not ideal, it is the truth. Due to massive bouts of migration the cities have become terribly congested places to live. And the builders in cities like Mumbai are looking towards only one solution, to go upwards. They are not entirely wrong. With urbanization and rise in population density this becomes the most practical way to deal with the crisis and with time the pros for high rises are going to outweigh the cons.

Architecture is not a rigid discipline; the best thing about it is that it evolves itself to suit the changing conditions. So maybe the answer is the increasing skyline. But that does not mean the basic fundamentals, which constitute good architecture, need to be compromised.

Most of Mumbai lives in squatter settlements scattered all over the city and comprise of different communities that have migrated to Mumbai in successive waves. They include the poorest sections of the society and their living conditions are pitiful. However any slum in the city is bustling and diverse, with a flare of its own. The people interact with each other in whatever community space they can find and have set aside their differences and their hearts beat as one; their entrepreneurial spirit and pulsing pace is what defines Mumbai.

This thriving community life is what sets Mumbai apart from the rest of India and what needs to be extended to the high rises, the luxurious abodes of the rich, rather than just aping the west. A city’s architecture can change to meet the demands as a world city, reflect the century’s advancement in technology and still be termed as good architecture. But is this ideology being employed? Or are the high rises just a tool for the short-term gains of the builders?

The towers today have all the amenities one requires to live a luxurious lifestyle. But has the quality of life now being reduced to quantity rather than quality? A tower absorbs more people on a smaller area, one may exclaim that so many families at one place must provide an interesting community. People there must have multiple platforms for social interactions. But the truth is different. In the corridors and lobbies of these buildings, a sense of loneliness prevails. Due to lack of open and community spaces, there is social disharmony. People live in their own cocoons and do not socialize.

Human beings are social animals. We are not supposed to live like rabbits in our own hutches. India is a country where everything begins and ends at community. And residential towers take that away from us. A residential tower, which meets our requirements of street culture, open spaces and verandas, is what would bridge the gap between the different classes and communities, which these tall towers have created.

“All architecture is shelter, all great architecture is the design of space that contains, cuddles, exalts, or stimulates the persons in that space.”

These words, spoken by Phillip Johnson, state as to how a space must respond to us and we to it in order to it being called a home. Apartments today have all possible luxuries but no scope of dynamic life. No continuous activity among the dwellers of different apartments. Just an apathetic placement of modules, with no sense of belonging.

The new architecture of Mumbai, and other megacities of India, is creating a world, which is repetitive, unnatural and harmful to the planet we live on. Unfortunately, Mumbai’s architects and urban planners are obsessed with building taller and faster, not with the footprint of cities, or open spaces and partnerships between classes and communities. The concrete jungles are just a competition between the builders and between the rich, and a preoccupation with size to display power, strength and stability. They could not be more wrong. This ideology is just an extension of the superficiality of this century.

Architecture is not about exterior facades or the dynamic presence a structure exudes. The external play is only the ego of the architect speaking. But good architecture is more humane than that. If what we build changes the life of other people for the better, then we are on the path to revolution.

“To touch the soul of another human being is to walk on holy ground.” -Stephen Covey.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |