[ID:2183] Culture | The DeterminantIndia THE UNINTENTIONAL UTOPIA

AUGUST 2016, BHOPAL : “A week more and the relocation process begins... - echoed the sound of the BMC (Bhopal Municipal Corporation) officials. The ruthless machines snapped and shattered our humble construct at the roadside. The demolition shrills pierced through the feeble mud walls. The walls roared from the strike of bulldozer. Dust from the wreckage and the cries of pain seemed to be choking all of us.”

Five months have passed, but the whole situation is still on tenterhooks.

“The glimmer of the morning sun broke through the cracks on the tinned roof, illuminating the room. The mother’s scream ferried Kamal from the utopian world of desires to the ghastly reality - a reality full of despondency and uncertainty. Springing off the cot, he hoped to shield himself from those strident noises and hid behind a door curtain”, Kamal’s grandfather, Biharilal narrated dismally, gasping for air more than once in between. [*1] I could not help but listen to his anguish, sitting motionless on the charpai (traditional Indian woven bed), at the entrance of his 25 square metre dwelling. The gut wrenching sound of his life’s work being torn apart reminded him how helpless he was. All he could do was witness the ruthless machines dismantle everything he had banked on throughout his life. This wasn’t the first time Biharilal and his family had been forced to fight an impregnable battle against the ones in power - the ones who mattered. This horrific feeling of displacement was neither new to him, nor to the remaining 300 plus members of the community.

Biharilal, 70, is among the first generation of people from the potters’ community who were displaced from their original place of livelihood, the main marketplace, over three decades ago. They were forced to settle in, Shastri Nagar, what was then, a remote part of South-Western Bhopal, the capital city of the Indian state, Madhya Pradesh.

In 1984, the then Prime Minister of the country, Indira Gandhi, just a few months prior to her assassination, passed the ‘Patta’ Act, (The Madhya Pradesh Act #15, 1984) entitling any landless person, like many in the potters' community, with a leasehold right on a 25 square metre ‘patta’ (a piece of land) each. It has sheltered thousands of such people ever since. Once the ‘Patta Act’ was passed, these potters were shifted from the main marketplace to Shastri Nagar; re-establishing their business from scratch was the only option they were left with. Against the grain, the potters’ began the new settlement process. They were joined in by migrants who wished to earn a crust, working as construction laborers in the city. Bhopal had been flexible enough to realize the distinct fragrances of cultures emanating from the relics, making the city architecturally affluent. To this caboodle of diversity of the city, another unique architectural style, revealing the potters’ community, was about to be integrated.

Shastri Nagar, ironically named after the second Prime Minister of India, Lal Bahadur Shastri (,a popular proponent of Self-Reliance), has changed a lot over the years, not just in terms of structures but also mindsets. This area, which is now as urbanized as the rest of the city, is home to some of the city’s most posh residential colonies. But, somewhere amidst the glare of these colonies lies the overlooked settlement of the potters’ community. The settlement, which through a common man’s eye, in terms of typology of buildings, resembles a slum.

“It’s no more the roosters’ crowing which wakes us up at the dawn, it’s the honking of the school buses, which do so! The time has changed. The mornings which begin with the prayers, that the next time we wake up - we do so in this same home of our’s. It’s the same piece of land, the land which has nurtured us all this while…”continued Biharilal in our solemn conversation. He was kind enough to serve us tea in a ‘Kulhad’ (terracotta cup), which exuded the soothing, earthy aroma.

A piece of land which was supposed to house just a man and his wife, back in 1984, now after three decades, serves 16 other members of the same family as well. The family has grown, so have the needs. Biharilal, lives and earns with two of his successive generations, in the same, a mere 25 square metre ‘patta’. To make this feasible, his dwelling, like many others’ in his community, has gone through a never ending series of alterations. It’s the tremendous evolution of the spaces, that has made it possible for such a meager piece of land to serve the vital purposes, which are a prerequisite for keeping their body and soul together.

THE ARCHITECTURE WITHOUT ARCHITECTS

“Back in 1980’s, with whatever financial resources we had with us, we began with the construction of an enclosed space by erecting, one-and-half feet stone walls and provided a roof covering with just a sheet of cloth. The main aim was to create some enclosure from the wild, because it was more of their dominance than ours' - the new occupants of the land." The presence of an open sewage canal adjoining the land made it even worse. The land with it’s three metre front towards the main road extends eight metre deep inside. The total level difference of about two and-a-half to three metres between the two ends was put to use, as a segregational element. With time, new working spaces were created at the mezzanine floor. “As the days passed by, we began getting acclimatized to the hardships, the place presented us with. The whole settlement enhanced and expanded with the gradual passage of time, so did my family. Good times seemed to roll, when the muffled stone walls exalted with the cheerful laughters of my four sons and a daughter…”, continued Biharilal, with a tinge of smile. The smile which was a revelation of his joy, that has been burdened beneath the weight of misery. [*2]

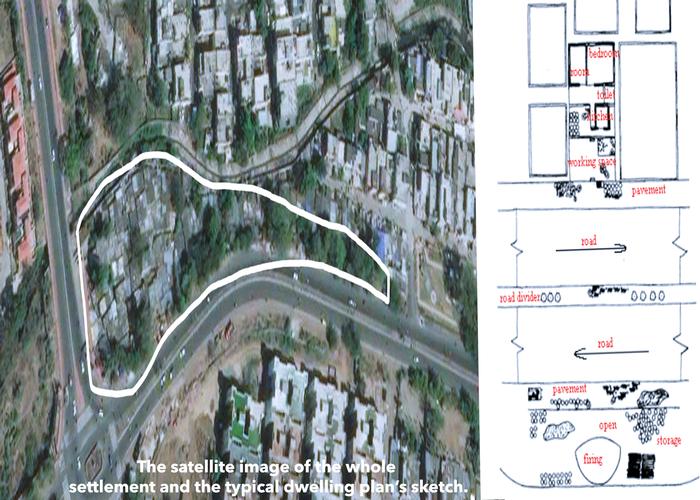

Structurally, the architectural form, specially the spatial arrangements in each of the dwellings of the whole potters’ community, speaks aloud the unique community it belongs to, demonstrating their presence in the urban fabric of the city. In a stretch of about 500 metres, running along the main road, these dwellings share a lot of common features. A dead ringer to most of the dwellings, Biharilal’s dwelling begins with a 10-15 centimetre raised mud platform, where the final pots are kept on display, for sale. To counteract the level gradation of about three metres from the beginning to the end, the whole dwelling has been divided into three different levels, finished floor level of each being a metre below the previous.

Moving inwards from the selling space, mud steps have been provided to cover for a level difference of about a metre, down the finished road level. This opens up at a seven-eight square metre ‘working and storage space’, where the potter’s wheel and several other tools required by them are installed. This space also stores the raw material like clay, and half burnt pots. Moving further below, narrow steps lead to the mezzanine floor. Being a tradition among the families of the community to have their meals together, with all the family members sitting on floor, majority of the dwellings have a small space adjoining the kitchen at this mezzanine floor. This, being placed centrally in the plan of the dwelling, makes it easily accessible for all the members. Further, creating a void separating the working space from the low lying private space. This lowest portion acted as a nucleus, through which the whole dwelling expanded upwards towards the entrance.This is the part, where Biharilal constructed his first stone enclosure - the one he talked about, previously in our conversation. This part of the dwelling now comprises few more bedrooms, one for each of his sons’ families, separated from each other by unplastered, clay brick walls. Apart from these bedrooms, the dwellings even have proper wash areas at this lowest level. These are intentionally placed adjacent to the sewage canal so that the waste soil and water generated can be provided a direct outlet, without investing much on the sewage piping systems. Due to the space crunch they are bound to, each and every available space has been put to use. Even the road divider, because of an all-day exposure to direct sunlight has been put to an advantage, which, acts more like a verandah, frequently used for drying pots.

As and when the business flourished, the additional storage spaces for the imported pots and other products also came up, either inside or outside the dwelling. As a result, some of the good profit making potters’ families in the community have even expanded their dwellings up to two storeys, which further reflects the endless evolution in the spatial organization of the structure. The dwellings of this potters' community, which were built by the potters themselves fulfill the basic livable requirements with just the use of locally available, sustainable construction materials. To bring into light, clay bricks and mud have been used for the internal partition walls ,clay being in abundance in this part of the country. Mud on the other hand, being an effective heat insulator, lowers down the net absorption of heat, in turn keeping the whole structure relatively cooler in the blistering summer heat of the city, vice versa during winters.

Ecologically, these dwellings are much more climate responsive than their modern counterparts, which rely ruthlessly upon the mechanical means to reach the optimal comfort levels. These dwellings profess the emerging, ‘Green Architecture’, by using sustainable construction materials and Intricate spatial placements. Extracting the most from whatever has been made available to them, they have found their feet without banking on the mechanical means.

Economically, the mean monthly income of a typical potter here, is a mere seven thousand rupees (approximately 105 USD), that too, has gone up as a result of some relatively high earning festive seasons like ‘Navratri’ [*3] and ‘Ganesh Chaturthi’, wherein the monthly income reaches to about fifteen thousands (220 USD) itself. With these meagre income levels, managing to achieve what they have in terms of architecture, is a tough row to hoe. Unlike the upscale constructions happening on the name of ‘modern living’, the architectural form here, is rich in revealing it’s identity. Their form doesn't need a name plate at the door step or a towel hanging in the balcony of a 15th floor apartment to act as a reference for recognition.

The self-developed form of the whole settlement has been able to serve the socio-cultural needs and endeavors of the community to excellence. Nevertheless, they are still deprived of the basic services like electric supply, proper sewerage connections, access to potable water, to name a few, which are imperative to a comfortable living. This is, neither in the hands of occupants, nor has the state been adept to provide.

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE COIN

What was the government’s motive and thought process behind the proposed relocation? This question haunted me every time i came across the grief-stricken potters’ families. Not being able to comprehend the reason behind it, a visit to the Bhopal Municipal Corporation (BMC) office, a few metres away from the potters’ settlements, made me come across Mr. Alam Gir, one of the urban planners there. Hardly to my surprise, it was all under another scheme. The ‘Make Bhopal Slum-free’ scheme, launched under the Chief Minister of the state, Mr. Shivraj Singh Chauhaan. This wasn’t the first attempt for this cause. As under JNNURM (Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission), a massive city-modernization scheme launched by the Government of India under Ministry of Urban Development in December 2005, a multi-storied housing just in front of these potters’ settlement has already been constructed. The designing of these housing under JNNURM, got off the wrong foot. It seems as if, the work culture and other major restraints with the aged members of the community, weren’t given a thought.

“How can they expect a 70 year old heart patient to climb the stairs to the third floor everyday? ”, complained, Biharilal’s feeble wife, Shantikumari, while shaping the mud ‘chulha’ (stove) to perfection. These, three-storeyed residential apartments are good for the office-going people, but for these potters, the various spaces they needed for the whole process of pottery were missing. There was no provision for the making and selling space of the pots, which meant either they had to find another place for the selling pots or switch to some other occupation. As a result, some of the potters who were willing to switch to some other work, shifted to these apartments. This comprised not even one-thirds of the total potters’ community. Rest of the apartments are now being occupied by the construction laborers and the clerks. Jean Nouvel once said, “Each new situation, requires a new architecture”. This falls apt for the situation faced by the government, while designing the housing for the potters’ community. A different architectural style, with design elements exclusive to the potters’ requirements, was what they couldn’t come up with.

Back in 2012, during my schooldays, I, volunteered for an international environmental organization, ’350.Org’, in an awareness program for the slum dwellers, regarding the benefits of switching to the renewable sources of energy, solar panels in particular. That was my first interaction with the slum dwellers, which left a clear imprint on my mind about their perception. They are deeply attached to their traditions! But, on the contrary, if provided with a suitable substitute, they do not hesitate to incorporate it in their lifestyle. This is similar to the case with the potters’ community, here in Bhopal.

At our end, there is no particular planning for a specific craft as per their work culture and lifestyle. As global becomes local, the international style of architecture dominates every skyline, irrespective of the climate and culture of the place. This new genre of architecture is very much cut off from the traditions and dismisses the traditional knowledge base developed over generations, threatening traditional and cultural values by the forces of economic, cultural and architectural homogenization. This has brought disregard for traditional environment and often considered as a symbol of poverty and backwardness.

“Vernacular architecture doesn't go through fashion cycles. It is nearly immutable, since it serves it’s purpose to perfection.” - Bernard Rudofsky, in his book, ‘Architecture without Architects’.

Now, an aspiring architect, I believe, one has to look into the intricate peculiarities in the distribution of the spatial elements inhabiting the space, which are a direct consequence of the culture, climate, topography and the requirements of the occupant. Its the amalgamation of these distinctive spatial elements, that leads to a viable form. The vernacular architecture of this potters’ community ratifies ‘Culture’ as the form determinant - a form which demonstrates the community’s presence in the city’s fabric and at the same time minister to its socio-cultural needs and endeavors.

— [*1], [*2] Manuscripts of the conversation translated and edited by the author. — [*3] A festival dedicated to the worship of the Hindu deity Durga, which goes on for nine nights.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |