[ID:1969] Addressing homelessness-for the people, of the people, by the peopleIndia While on a family holiday in Madrid, towards the end of September, I was quite astonished to see a large number of homeless refugees camped at Plaza Cibeles, right in the heart of the bustling city. Back home in India, the site of homeless people on the streets is quite commonplace, but on the stately streets of the Spanish capital, something seemed so amiss. Although, I had heard news of the refugee crisis, seeing the consequences firsthand led to a deep sense of dejection. Dejection about how fellow human beings for countless reasons may be forced out of their homes, their places of comfort, to camp on the footpaths of unwelcoming, alien neighbourhoods.

UNDERSTANDING WHAT CAUSES HOMELESSNESS

No one is homeless of their own choosing. It always is an outcome of circumstance. Homelessness is not the root of the problem. It is symptomatic of a larger malaise, which may either be poverty, natural disaster, epidemics, wars or economic upheaval. Homelessness is not just a mere lack of physical shelter. It is an extreme lack of social support, a failing of the system, making pariahs of those most in need of a support system. Martin Kämpchen writes that “poverty is not just a state of material deprivation. It is far more complex than just a lack of clothes, shelter, food.” He also states that “material poverty creates an emotional and mental environment of poverty. The mental horizon of the poor is marked by existential uncertainty and constant fear of change in the precarious balance of their life. They want stability, but most of them lack the intellectual, practical and technological skills needed to find a way to achieve it.” This is particularly true when it comes to homelessness. A sense of helplessness and stifled needs propagates homelessness. In Mumbai, the financial capital of India,according to the 2011 census, the number of people living without shelter (excluding slum dwellers) is 57,416. However, according to the Indian Express, activists claim that the actual number of homeless people may be anywhere between three to four lakh, almost 8 times the official figures. Such apparent institutional apathy for the homeless populace shows just how marginalized they are. A factor common to homelessness across societies is our indifference towards it, and moreover, the stigma faced by the homeless.

THE BHUJ EARTHQUAKE

On the 26th of January 2001, a catastrophic earthquake struck the western Indian state of Gujarat. It is still considered one of the worst natural disasters to have ever struck India. In its disastrous aftermath it left 1,79,000 people homeless (according to a OCHA report). Apart from homes, the social infrastructure - medicinal facilities, schools, telecommunication and power lines, sanitation networks, water supply - was completely disrupted.

A friend and fellow architecture student, Sunil Patel, was residing in Bhuj, very close to the epicenter of the quake when it struck. When the earthquake struck he was in school attending a Republic Day celebration. He recounts the days immediately after the catastrophe, when missing neighbours and going hungry for days were their immediate concerns. Thankfully no one from his family was hurt. They were some of the few lucky ones to escape unscathed, physically at least. But they lost everything tangible, their ancestral property, their belongings, their livelihood, everything. It was a traumatizing time. Sunil’s family had distant relatives in Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu. Consequently, they decided to migrate and start anew there. “I don’t know what would have happened if I stayed back. Most likely I wouldn’t have been educated and I definitely would not have been in college.” He has mixed feelings about Bhuj now. Although he does want to go back and see what has become of it, he is happy his family got out when they did. Their extended family helped them through the few years immediately after the quake. But for many other survivors in Bhuj, the lack of an effective support system meant facing hardship for so much longer. This was especially true for the numerous villages in the Kachchh district. Many of the villagers in far-flung villages, being illiterate and unaware of compensation schemes, were unable to assert their claims. These were some of the worst affected victims of the quake. Subject to the extreme weather conditions of the Kachchh desert, with no resources of their own, no social infrastructure to bank on, and virtually no compensation coming their way, their situation was bleak.

REHABILITATION RESPONSE

Responding to massive public outcry, the Gujarat government, in its eagerness to find a fix, embarked on a large-scale rehabilitation programme which included relocation and village-adoption as strategies for the affected villages. This model was similar to that employed by the Maharashtra state government for the rehabilitation process of the Marathwada earthquake (1993), which was financed by the World Bank. It entailed complete relocation of villagers to other localities while reconstruction work was carried out by hired contractors and masons. This also meant that non-local stakeholders became the majority in the rehabilitation process, lending an overly outside perspective to the outcome of rehabilitation. For long term rehabilitation though, reestablishing community life may be adversely affected by the over-reliance on outsiders during the course of reconstruction.

However, unlike in Marathwada, the local people in Kachchh strongly opposed the government’s plans for village relocation. Owing to this, the government decided to switch from plans of relocation and “contractor-driven” reconstruction to “owner-driven” reconstruction. The latter places the onus of rehabilitation on owners, with outside players acting as facilitators. Under this approach the government offered financial and technical assistance to all those who were against relocation. The different recourses offered to the people gave them the option to be completely independent and build for themselves, or engage with an organisation which would help facilitate the building process by providing technical expertise and guidance. Financial compensation by the government was given to affected families commensurate to their entitlement. Compensation for destroyed houses ranged from a minimum of Rs.40,000 to a maximum of Rs.90,000. Assistance in the case of damaged houses ranged from Rs.3,000 to Rs.30,000. To ensure that funds were not misused, the government released compensation in three installments parallel to house construction. Subsequently, to ensure that seismically sound construction was adopted, the second and third installments would only be handed over, after verification and certification by government engineers.

Given the choice, almost three quarters (72 percent) of the 272 affected villages chose to rebuild their own homes. Under the “owner-driven” reconstruction programme over 1,97,000 homes, corresponding to 87 percent of all destroyed homes were rebuilt. Decentralizing the process, and empowering individual stakeholders effectively ensured its long term success. Such owner driven reconstruction received unprecedented support in the form NGOs and international and national organisations coming forward to help with recommendations for design and technology of earthquake resistant structures. The implementation techniques and policies adopted made it a pioneering endeavor in post disaster rehabilitation in India.

Hunnarshala is one such pioneering non-profit organisation, set up in the wake of the earthquake. The precursor to Hunnarshala was a shelter cell started under the aegis of the Kutch Nav Nirman Abhiyan, a network of development NGOs in the Kachchh region. The founders were a consortium of architects, engineers and environmental advocates like Neelkanth Chayya, Tushar Dayal, Sandeep Virmani, Kiran Vaghela, Kantisen Shroff, Kirit Dave, Durgalaxmi Venkatswamy among others.. One of the factors that caused such massive loss of life and property during the earthquake was the poor construction quality of buildings. Recognizing the need for better construction technology, in 2003 Hunnarshala was founded as a non-profit company with the participation of Kutch Nav Nirman Abhiyan and contributions from educational and scientific institutions like CEPT, IIS, CSR Auroville and companies like HDFC, Gruh Finance and Transmetal Industries.

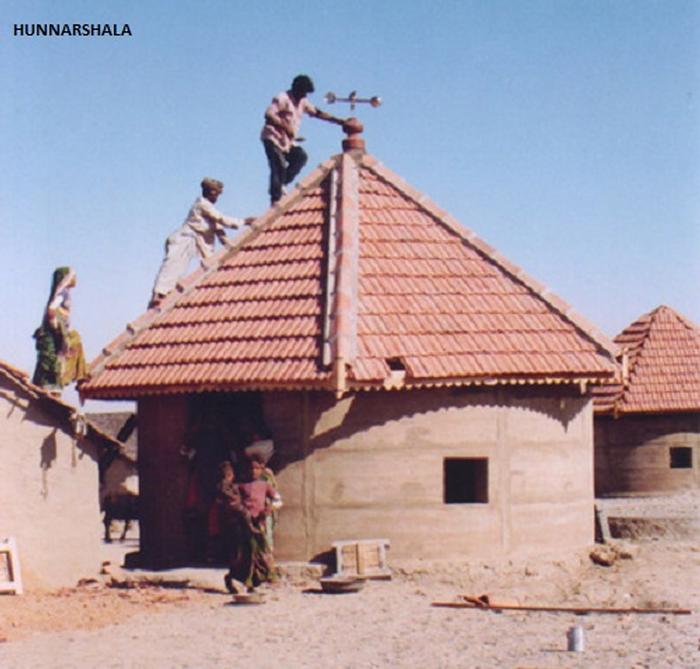

Right from its outset the cornerstone of Hunnarshala’s work has been community led implementation of vernacular building knowledge. Hunnarshala seeks to inform itself from the communities it works with. Working with locals in a symbiotic process, Hunnarshala revives and propagates traditional building practices that are best suited for the region. Hunnarshala also encourages villagers to take their newly acquired building knowledge forward and set-up entrepreneurial enterprises of their own. A prime example of this is the implementation of the traditional ‘bhunga’ construction for the post-earthquake rehabilitation of numerous villages.

In post disaster reconnaissance, it was found that the ‘bhunga’ (a circular hut made of thick mud walls), a traditional housing typology, survived the tremors unscathed. According to Hunnarshala, community elders claim that the ‘bhunga’ form was developed as a response to the 1819 earthquake, when building craftsmen from Kachchh and the neighbouring Sindh region got together and collectively devised an earthquake resistant building form. Subsequently, activists aiding with rehabilitation work in the shelter cell realized that such time tested building techniques could serve as a better repository for rebuilding efforts, rather than employing mass scale pre-fab technologies. As the rehabilitation work progressed, an urgent need for research regarding traditional building practices was felt. Since then, Hunnarshala has been involved with reconstruction efforts in the numerous villages in Kachchh.

Hodka, a sleepy village in the salt plains of the Kachchh desert, is one such village where the reconstruction process was facilitated by Hunnarshala. Unlike other organisations which, with a more hands-on approach, are actively involved right from the planning and design to the construction management stage, Hunnarshala trains the local community in traditional artisanal construction methods. Further, these community-backed artisans in conjunction with individual owners would build bhungas as per the owner’s requirement. Aid in the form of technical know-how and construction material was provided by Hunnarshala. Nurabhai Koli and his family reside in a bhunga home in Hodka. He proudly recalls how fellow villagers Ramaben Vela and her husband Bhimabhai had helped in constructing his home. The construction of bhungas on such a scale was only possible because it was a largely community driven effort. Such collective action towards a common goal aided in reestablishing social and communal ties after the shock of the quake. He explains how the bhunga being a small hut of 3-6 m span, is used as an individual room; a group of such bhungas built on a rammed earth plinth functions as a family home called a vaas. This plinth usually covers the future expansion of the vaas. While planning a vaas, initially an earthen stove for cooking and two bhungas for living/ sleeping are constructed. Additionally bhungas are added as when the family expands, thus this typology is ideal from the incremental housing perspective.

The bhungas are characterized by thick stabilized rammed earth walls which are reinforced with steel rings at regular vertical intervals. Alternatively, sometimes the bhunga walls are made of stabilized earth bricks. The advantages of using local earth are manifold: not only is dry earth easily available, thus reducing dependence on external agencies to deliver construction material, but, earth, also successfully resists the large diurnal temperature variations, where another material like concrete would have cracked. The thick mud walls act as insulators, keeping the interiors of the hut cool in the sweltering 45-50? C summer heat and conversely warm in the winter months. Due to their circular configuration, thick mud plaster and their conical roofs, the bhungas are able to withstand the frequent desert winds and also the not so frequent, ever present danger of seismic activity. The circular form works as an arch in the lateral movements of an earthquake, strongly holding the walls together.Bhungas generally have only three openings (though variations do exist),the entrance door and two small and partially or completely latticed windows. The conical roof of the bhunga is supported at its apex by a vertical wooden post supported on a horizontal wooden joist. The base of the roof and the wooden joist are supported by the bhunga wall. Sometimes to reduce the load on the walls, two diametrically opposite wooden poles, anchored outside the bhunga wall take the load of the wooden joist. Traditionally, thatch was the roofing material of choice, and this continues to this day. In some instances though, owing to reduced fire hazard, lower maintenance and better performance in cyclones, villagers have switched over to octagonal framed roofs with clay tiles as roofing. In the years since the earthquake the widespread adoption of the bhunga has made it something of a cultural symbol of resistance. It has become closely linked to the image of life in the Kachchh dessert. It is almost poetic, I think, that the craftsmen and artisans of the culturally rich Kachchh region are fittingly housed in well-crafted houses.

Seeking to replicate “owner driven” construction in the case of urban slums, Hunnarshala with support from the government is working on slum rehabilitation projects in the city of Bhuj, under the Rajiv Gandhi Awas Yojana scheme. This undertaking seeks to empower the slum dwellers by taking their inputs into consideration during the design stage. The project is still in the implementation stage.

CLOSING NOTE: COMPARISON TO THE CASE OF LAKHNU

Lakhnu, is a quiet, little, forgotten village in the hinterland of Uttar Pradesh, not unlike Hodka. A joint workshop with Curtin University, Australia, in February 2015, opened my eyes to a facet of India that, quite honestly, hitherto, I was unaware of. The workshop involved documenting the region, its people, constructing community toilets and making non-intrusive changes in dwellings to improve the quality of life. This particular exercise is the fifth consecutive year that Curtin university has been working with the people of Lakhnu. The activities are partly funded by Curtin university and partly by an Australian NGO in Perth, Indian Rural Education And Development (IREAD) which was set up by a Mrs. Sharma, whose grandfather was the Sarpanch (village head) of Lakhnu. The majority of breadwinners in Lakhnu are young men either employed as farmhands or construction workers, while women take care of the household (a very small minority of women work as farmhands). Their meager earnings are spent on basic necessities -food, clothes,medicines- for themselves and their families, leaving very little money for other essential requirements such as home improvement, sanitation etc. Homes of the villagers are very often health hazards in themselves. The poorly ventilated homes mean that smoke from indoor wood-fire stoves (chulhas) stifle the residents of the shanties. In some houses, dry bramble and asbestos sheets (despite their use being banned in India) are used as roofing material, leading to further health complications when water leaks into the houses.

Learning and adopting from the “owner construction” model of Hunnarshala’s, which focuses on spreading knowledge to the locals and empowering them to build their own homes, I hope that someday, the plight of Lakhnu’s houses may be elevated. The building technologies would have to be altered to cater to Lakhnu, where clay bricks are the material of choice. Through research and collaboration with the locals, innovative roofing materials could be developed using locally available raw material. Maybe, sometime in the not so distant future the villagers of Lakhnu will explain to us how their newly devised clay tiles have to be fitted.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |