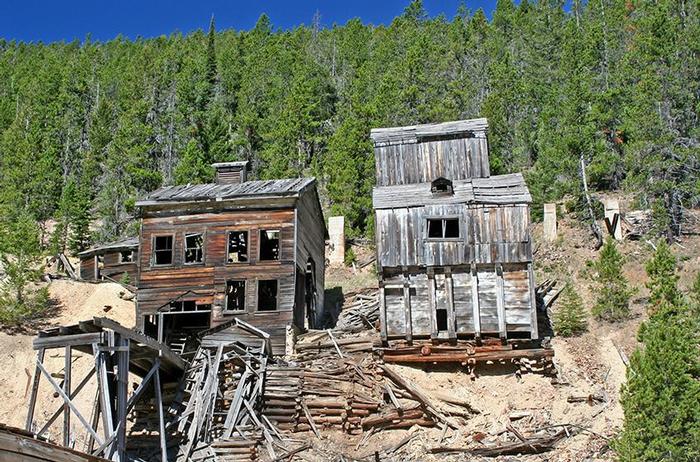

[ID:176] Remnants of a Mining TownUnited States The rundown road is overgrown with weeds and crisscrossed with streams; the four-wheel drive vehicle can hardly traverse it. At the road’s end stands a collection of derelict buildings, the mining ghost town of Hughesville, buried in the Little Belt Mountains of Montana. Hughesville is one of the few mining ghost towns in Montana that stands without any preservation efforts. Once one of the leading lead and silver mines in the state of Montana, Hughesville now deserves historical documentation. In this unique setting, the viewer can, by simply looking around, clearly envision what a Montana mining town at the turn of the twentieth century looked like.

Step out of the vehicle at the end of your bumpy ride. The sound of singing birds fills the air; as you breathe, the cool mountain breeze brings the scent of forest to your nose; close your eyes for a brief second and hear the creek gently flowing past the weathered wood of a building. Open your eyes to find yourself standing in the middle of an aged town, surrounded by houses extending off the side of the mountain, encompassing a large building with the creek running through it at the base. Peeking inside, you see remnants of old smelters and boilers. The mining shafts are still present; do not venture down into them, however, since they are flooded and unstable. Though some lean from structural degradation, many buildings remain standing despite the punishment decades of harsh mountainous climate affords: beating rain, strong winter winds, creeks running through them, and foliage rooting in their timbers. The wilderness’s reclamation of this landscape from the physical marks left by man yields a spiritual link to the past.

“…as music of sweet sounds, or painting of fair colors, but of inert substance, -- depend, for their dignity and pleasurableness in the utmost degree, upon the vivid expression of the intellectual life which has been concerned in their production.” John Ruskin

Any visitor can perceive the presence of an undefined past, but the significance of this ghost town’s story is partly found within knowledge of its history. Knowing a place’s history transforms it in the imagination; a path in the trees becomes the rail line that was torn up many years ago, gatherings of depressions in the ground becomes a tent camp for miners, and an expanded bank on the creek becomes a gathering place for women washing clothes and miners relaxing on break. Knowing the ghost town’s history is not necessary for feeling its past, but it does greatly enrich the experience.

In the spring of 1879 two gold prospectors by the names of Patrick Hughes and E. “Buck” Barker discovered silver and lead deposits in the area, and mining camps sprang up almost immediately. Hughesville was formed when the mining camps of Hughes City, Galena City, and Leadville combined to create the mining town in the summer of 1879. The lead and silver that was found in the mines was then placed in wagons and taken north to Fort Benton, MT.

“A convention is not to be valued primarily for its novelty, beauty, or internal consistency, or for its autonomy, or for the law and order it brings to practice, but rather for its true or liberating relations to other conventions of practice.” Stanford Anderson

The path taken by wagons to Fort Benton was eighty-three miles long and would have taken roughly a week and a half in one direction. The path would have been treacherous yet beautiful since it led through the majestic mountains, standing mostly untouched by man at the time. Today this stretch of road has its twists and turns but as you follow the riverbed the view as the canyon walls open up is still breathtaking: one sees the mountains rolling out into the massive hay fields. After the journey to Fort Benton, the lead and silver ore would be placed on steamboats, then sent to England to go through the smelting process. A smelter was built in 1881 by Colonel G. Clendenin in Barker, another mining town not two miles away, increasing the profits for the mining company which no longer had to sell raw ore for shipment. The life of the smelter was cut short in 1895, however, when it was destroyed by arson; the mining town had to ship their ore for smelting once again.

The transportation of ore became less strenuous after the installation of a Montana Central Railroad depot in Barker. This outlet allowed the ore to travel to smelters in Helena (one hundred thirty-three miles), Great Falls (sixty-one miles) and Neihart (seventeen miles). The miners must have been relieved to use the train instead of relying on wagon transportation.

Hughesville survived hard times in the Panic of 1883, considered the worst depression the United States experienced before the Great Depression. Mining towns were hit especially hard and many did not survive because this depression was closely tied to silver prices and railroad overbuilding. Hughesville did not fare well in this silver crash and dwindled to a population of forty by 1889. Market changes continued to affect the mine; it and its surrounding properties switched hands over a dozen times during its active lifespan. Hughesville, once the largest lead producer in Montana, remained a sporadically active mining town until 1943, when it closed with finality.

Looking at the ruins of a mining town that was once so industrious makes the viewer wonder what it looked like during its prime. The layout of a typical mining town would depend on the location of the site. The site would determine whether the buildings would be positioned on a grid system, placed randomly, or situated along one single road running through town, a popular choice at the time. Due to the tumultuous terrain of Hughesville’s location, a scattered layout was chosen for the town. Before any mining could commence in 1879, the mines and operational buildings needed to be constructed. The company would set up tent cities to house the workers during this period. These tent cities would be left up in case a housing need developed. Since this was a mining town, the single men of the mines needed sources of entertainment; at one point this resulted in fifteen saloons and one brothel. Of course, with a peak population of fifteen hundred, housing dominated the town’s landscape. Bunk houses, built to accommodate the large numbers of miners, prevailed over single residences. In addition to the housing, there was also the general store and a church. Most of the houses are gone, except for the handful that still cling to the side of the mountain.

"The trace left behind is substituted for the practice. It exhibits the (voracious) property that the geographical system has of being able to transform action into legibility, but in doing so it causes a way of being in the world to be forgotten." Michel de Certeau

The buildings did not meet the three basic points of architectural design, but they did meet the one of the most basic needs humans have, shelter. Their construction was practical and did not intellectually challenge the residents, or (with exception of the chapel) uplift their spirits. The natural surroundings, however, provided the grace and beauty the buildings were lacking. The townsfolk were provided with this pristine space, and left their mark by being present, building, and simply dwelling there. Now the ground here is hallowed by their absence, the residual cathexis of its residents left behind for present day visitors to sense. Even though Hughesville started off as one of many typical, workaday mining towns lacking any kind of numinous, it achieved it over time from the imprints lives past left on the remaining buildings, and by the aging buildings in turn telling their story.

“…this is especially true of all objects which bear upon them the impress of the highest order of creative life, that is to say, of the mind of man: they become noble or ignoble in proportion to the amount of the energy of that mind which has visibly been employed upon them.” John Ruskin

In the aftermath, the town has become spiritual, the lives and experiences spent in Hughesville have created a spiritual fingerprint of sorts. While the buildings, inhabited and given purpose by the miners, might enhance the site’s sense of transcendence, without the lives that passed through it Hughesville would be merely dry timber and played-out tailings. The mining activity is dead but enduring traces of the breath and the heart of the community remain. Even though Hughesville’s remains are present, that doesn’t mean it should be preserved. Hughesville should be cherished and remembered, its buildings allowed to carry out the remainder of their lives.

“Organic buildings are the strength and lightness of the spiders' spinning, buildings qualified by light, bred by native character to environment, married to the ground.” Frank Lloyd Wright

The main characteristic of this site is how long it has been untouched by construction. Nature has been slowly reclaiming the area as its own. For almost seventy years the town has lain dormant, absent of the miners and their industry. But it stands yet, a proud reminder of Montana's rich mining history. Documenting the site would be appropriate while it is still in relatively good condition because it is such a valuable piece of history. Few abandoned mining towns have detailed documentation of their final years before they collapsed into ruins. Additionally, it would be wise to have a designated individual check on the site twice a year to ensure the buildings are safe for those visitors who do stumble upon the town. Although fallen trees and similar obstructions should be removed from the road for safety reasons, it should not be groomed because its primitive state is such a key part of the experience. However, I would not advise extensive intervention in the site or restoration of the buildings. The examples of the side-by-side mining towns of Virginia and Nevada City in Montana, which were restored to serve as tourist attractions, illustrate what Hughesville stands to lose through restoration. Virginia and Nevada City’s old buildings have been repurposed to house shops selling souvenir baubles and delis serving designer sandwiches. They are presented as historical learning experiences, which is true to some degree, but those towns have been stripped of their spirit for the sake of modern consumerism.

Like an old man sitting in his easy chair telling stories of years past, the decaying buildings tell their own stories as they settle into the earth. To alter this site for heavy tourist traffic would take away part of its poetic story, erase its numinous qualities. Instead it should be documented and allowed to live out its remaining years. By allowing the buildings of Hughesville to complete their full life spans unaltered, not only can we watch their story unfold, we can also allow the spiritual fingerprint of lives past to gracefully become a part of the earth yet once again.

References

McClanahan, M.S. (2008). Hughesville – Montana Ghost Town. Retrieved January 5, 2011, from http://www.ghosttowns.com/states/mt/hughesville.html

Weiser, Kathy (2008, August). Barker & Hughesville - Ghost Camps in the Little Belt Mountains. Retrieved January 5, 2011, from http://www.legendsofamerica.com/mt-barkerhughesville.html

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |