[ID:1409] Incremental Changes Bring Immense Happiness to the Urban PoorIndia In her 1989 semi-autobiographical movie, In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones, Arundhati Roy plays the role of a final year student of architecture, Radha. The city, Radha says in her final thesis presentation, consists of a number of institutions – houses, shops, roads, sewage systems et al. – institutions that are built by the architects and the engineers. These institutions are meant for the citizens. The non-citizen, the poor of the nation, “...has no institutions. He lives and works in the gaps between these institutions – he defecates on top of the sewage system…”. Sanitation is, indeed, one of the biggest challenges that India still faces. India accounts for around 600 million out of the total 1 billion people who don’t have access to proper toilets. Many people defecate in public areas which leads to serious health problems. The fact that about 1000 children, under the age of 5, in India, die every day because of diarrhea – one of the numerous diseases caused due to poor sanitation- is a stark pointer. The problem is exacerbated in the urban slums dotting the Indian landscape because of the highly congested living conditions of the urban poor.

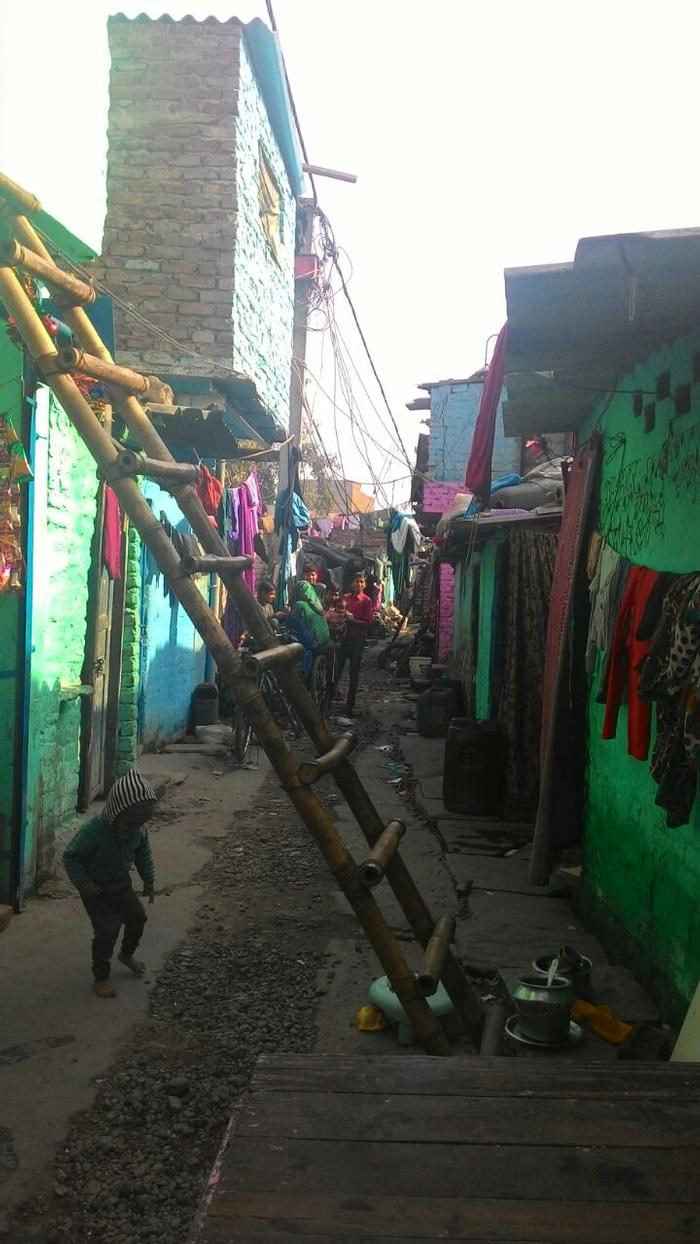

SafedaBasti is one such example - an illegal slum settlement of 650 families in east Delhi. The cluster sits on 1 hectare land belonging to Delhi Development Authority (DDA) near the banks of the Yamuna River, bordered by 30 m wide Pushta road which links the commercial areas of Laxminagar and Gandhinagar. The settlement is predominantly populated by migrants from other states of India who arrived in Delhi 30 years ago in search of livelihood. The average size of each household is five. The children go to a state run school in the vicinity. The growth of a slum is incremental in nature. The slum dweller starts with building a hut for himself consisting only of a multipurpose room which is usually not larger than 9sqm. This functions as the living room, kitchen and the bedroom for the entire family. As the family grows, he might add a room on the first floor. SafedaBasti has a range of dwellings in various stages of growth. What strikes us as we enter the Basti (settlement) is the bright color of the brick walls of the settlement (see Picture 1). The narrow streets are cemented but dirty. Two stormwater drains, clogged with solid waste, run parallel to the streets which are labyrinths formed by little jhopdis (hutments). The architecture of the slum is truly vernacular as the jhopdis are constructed by the dwellers themselves. Each jhopdi is a simple four-walled room capped with a temporary roof. We observe the details- the absence of finishes, the irregularity of the pointing, and protruding wooden beams indicate their primitive quality. Due to the absence of windows and the narrowness of the street, the jhopdis receive very little daylight and ventilation. We look around the settlement from the terrace of a jhopdi; a concoction of various materials- torn car covers, plastic gunny bags, old vinyl banners (functioning as the damp proof layer) pinned in place by stones atop asbestos sheets- make the roofscape of SafedaBasti. These structures remind us of the last minute assembling of models for architecture studio assignments which comprised of materials procured from waste in our dormitories painted with bright colors to hide the untidy joints. The skyline is cut across by crisscrossing rope lines, with clothes hung for drying, and electric lines entangled with each other. The streets provide the valuable additional space for activities which overflow from the cramped dwellings- we see ladies washing clothes and vessels on the streets. In contrast to the absent street life of the wide motorized roads of Delhi, the streets of SafedaBasti are thriving with activity- kids, cows, goats, women, old men are in harmony with the sharing of spaces.

For around three decades the people of this settlement have lived without a sewage system. The sewer lines pass parallel to the boundaries of the slum into the vicinal middle class locality of Geeta Colony. The authorities had deemed it fit to not acknowledge the existence of the slum. The inhabitants had been left with no choice but to defecate in the open - either in the overflowing open drains or on the banks of Yamuna River. A few years ago the government had constructed a community toilet complex inside the settlement. The CTC is the most spacious place inside the cramped settlement but it, too, faces problems. The complex is sublet to a private contractor who charges a nominal fee for using the facility and is responsible for its upkeep. However, the toilet complex was in a very bad state. Many of the WCs had broken down, some with their doors missing. Water, presumably sewage water, was flowing on the floor of complex. One could not set foot inside without getting the footwear dirty. Furthermore, the complex closes down every day from 10pm to 5am in addition to being closed for weeks altogether whenever there is a need for immediate repair which, we are told, happens frequently. This forces the inhabitants to fall back on the original mode of defecating. Going to the banks of the Yamuna is a graver problem for the women and children who, as a result, have been victims of sexual assaults especially during the nighttime.

Centre for Urban and Regional Excellence (CURE) is a Delhi-based NGO that is doing remarkable work in such areas to enable dignified living environments for the underserved urban poor. The institutions of the State, on the other hand, have a complicated relationship with the slums of the city. In one judgment by a bench of the Supreme Court headed by Justice Ruma Pal, the Court had been downright hostile ( “If you can’t afford to stay in Delhi, go elsewhere!”) comparing the provision of services to the slum-dwellers to rewarding of thieves. This was in 2006; there has been some improvement since. In 2010, the government of Delhi passed the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board Act which established DUSIB as an autonomous organization tasked with the role of looking after urban slums either by provision of civic amenities or their resettlement. It is in association with organizations like DUSIB that CURE has been able to make way for the improvement in the living conditions of the urban poor.

For SafedaBasti, CURE has come up with a simple solution of laying a sewer line through the Basti and connecting it to the City’s sewage system. But this required years of advocacy with various government bodies. The slum dwellers are supposed to construct a toilet in their dwellings by themselves. The greatest impediment to the betterment of living conditions in the slums is the fact that most of them are deemed to be ‘illegal’ by the State and thus fear imminent forced evictions. The slum dwellers do not want to invest their hard earned money at a place which they are not sure of retaining beyond a few years. It was this attitude- believes Yashomito, a humble shopkeeper living in the Basti for 17 years, who was the first to extend his support to the project- that was hardest to tackle. He believes that for however long people stay at a place they should do so in a dignified manner. Dignity, more than anything else, is important to him.

In the eyes of the middle class residents of the vicinal Geeta Colony, the slum-dwellers have no dignity at all. One of the residents, a property dealer in the area, compared them to vermin who will be thrown out as soon as the elections are over (The state elections are due on Feb 7). Most did not even know the name of the Basti – only when we said JhuggiJhopdis, the local word for slums, did they realize what we were talking about. They see the slum as a nuisance that is a breeding ground for criminals in the area. The property dealer affirmed that some of the women from the Basti work as domestic help in Geeta Colony but quickly shrugged it off as being insignificant. No one had any idea about the laying of sewer lines in the Basti. They do not venture into the Basti, some even gave us unsolicited advice, “Do not go in there; it is a dangerous place!” The incidence of crimes ascribed to the slum-dwellers, the residents of Geeta Colony acknowledged, had gone down in the past few months but they did not know the reason.

The reason for the reduction in the crime rate is that the youth of the Basti have been involved in the project by CURE. Sensing that they had a chance to enter the mainstream of the society, those who had earlier been involved in crimes like thieveries in the area started working enthusiastically to ensure that they have a dignified life. Many of them became members of the resident welfare association (RWA) that was set up with the help of CURE. The RWA has been instrumental in enabling the dwellers to assert their rights. It also helped in outlining the whole project for the benefit of the slum dwellers who, after repeated betrayals by the politicians about provision of civic amenities, were skeptical about the project. The mechanism of the sewage system was made understandable to the slum dwellers by painting the streets showing how the household sewage will be connected to the sewers all the way to the City’s sewage system (see Picture 2). This helped the slum dwellers ward off their skepticism. Work on the project was in progress when we visited the slum. The enthusiasm in the Basti for the project can be gauged from the fact that some of households have already constructed a toilet in their jhopdis (see Picture 3) and eagerly await the completion of the project. It will take about two months, says Manoj who is the project manager appointed by CURE in SafedaBasti. Poonam, who is a member of the RWA, is looking forward to it. She says it will be a blessing as they would not have to compromise their dignity or safety by venturing out in the night to defecate. She is also hopeful that the incidence of diseases, especially among children, will be reduced after the project has been completed.

To see how such a project works out we went to Prem Nagar in South Delhi which houses a settlement of around 150 jhopdis. A sewer line has recently been laid in the slum and connected to the main sewage system – on similar lines as is being done in SafedaBasti. Prem Nagar slum is remarkably cleaner than SafedaBasti (see Picture 4). Krishna, who has been a resident of Prem Nagar for more than 20 years, says that the sewer line has been a blessing. She is visibly happy that her children no longer fall ill as frequently as they used to and can now focus on their studies. Is there anything else you want from the society, we ask her. “We have lived as a community for so many years and developed emotional bonds. Please do not throw us out and scatter us”, she pleads.

We had good news for Krishna but we didn’t want to raise her hopes yet. SK Mahajan, who is a senior engineer at DUSIB, had told us, earlier in the day, that there has been a gradual change in the official policy towards slums: from resettlement to in-situ development of slums. The urban poor have been found to run away from many resettlement colonies as these are usually located in the peripheries of the city and those areas lack opportunities of livelihood. The poor migrate to Delhi primarily to find means of livelihood; comforts like proper housing that the resettlement projects offer don’t mean much without the guarantee of a source of livelihood, says Dr. Renu Khosla – the Director of CURE. The successes of the projects at Prem Nagar and the enthusiasm shown by the residents of SafedaBasti to play their part in ensuring a cleaner environment in the slum can be instrumental in the total realignment of the government policy, acknowledges Mahajan.

Safeda Basti has had scant media attention, not all of it positive. A supplement of a national newspaper, Hindustan Times, has done a feature on the CURE project at SafedaBasti. Renu is unfazed. The media in the country works like this, it takes time for them to pick up such stories but when they do, especially if it is a success story, they usually come in flocks. A similar thing happened in case of Savda Ghevra, a slum resettlement project done by CURE on the western periphery of Delhi which ended up getting a lot of, even international, media attention.

The biggest takeaway from the project has been the power of participatory planning approach and social engineering that can be achieved through this. The residents of SafedaBasti have agreed to invest in the laying of the sewer line and actually participate in the construction work as labourers and managers. This makes the project truly theirs and this sense of belongingness within the larger community is important in projects that seek inclusiveness of the marginalised. As an addition to that, the vicinal community of Geeta Colony could also have been taken on board - with the architects playing the role of interlocutors- which could have acted as a starting point for the end of hostilities towards the slum dwellers.The provision of a sewer line is a necessary first step, the entry point to better the lives of the underserved, but by no means exhaustive. A sewer is indeed a better choice than a CTC in economic terms as the cost of laying a sewer pipe is about one third the cost of constructing a CTC with negligible maintenance in comparison to the high maintenance cost of a CTC; it also upholds the privacy and the safety of the users. The safety of the residents, we believe, deserves attention on other fronts too. Many jhopdis are far too dilapidated and can crumble down any time. The mobilisation achieved in the settlement on account of the project could be used to inspect the dwellings and to buttress the structures wherever need be.In the future, once the CTC becomes redundant, the comparatively expansive space can be adapted into some other use - a children's park for the community, say. This will provide the residents a necessary breathing space.

There are about a thousand similar slums in Delhi. Renu says that they had decided to do the project at SafedaBasti to prove to the State that this is something that can be done; they may already have been successful in achieving that. "Easily 40-50 % of the city slums can be linked to the City's system at lower costs till such time that you create proper housing for them", she adds.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |