Travel Fellowship Report: Diana MihaiArchitects Sans Frontieres-UK Workshop in Leh, Jammu and Kashmir, IndiaAugust 9-25, 2011  On a scorching morning in mid July, I embarked on a three weeks journey for my Berkeley Travel Fellowship in India. I took advantage of a long lay-over in Istanbul to visit Basilica Cistern, a subterranean structure that dates back to the Byzantine age, and after changing three planes, I arrived in Leh where I joined the other workshop participants. As Leh is situated at an altitude over 3500 meters, we had to take complete rest for three days in order to avoid altitude sickness. On a scorching morning in mid July, I embarked on a three weeks journey for my Berkeley Travel Fellowship in India. I took advantage of a long lay-over in Istanbul to visit Basilica Cistern, a subterranean structure that dates back to the Byzantine age, and after changing three planes, I arrived in Leh where I joined the other workshop participants. As Leh is situated at an altitude over 3500 meters, we had to take complete rest for three days in order to avoid altitude sickness.

The workshop began with an introduction of Architects Sans Frontieres-UK’s philosophy, the NGO responsible for facilitating the workshop in Leh. We learned that the organization aims to help Building professionals develop their skills of working with people by setting up multidisciplinary teams and exposing them to challenging contexts. Our group consisted of 17 members with backgrounds ranging from Architecture to Building Surveying. Later, the introduction was followed by a screening of ‘Ancient Futures: Learning from Ladakh’, a film based on the eponymous book written by Helena Norberg-Hodge. Founder of the International Society for Ecology and Culture, Norberg-Hodge was one of the first people to arrive in Ladakh after it opened for tourists in 1975. The film depicts the traditional culture of Ladakh that remained unchanged for centuries until modernization took its toll. Previously a self-sustaining and strong culture living off the goods of the land, Ladakhis are now dependent on external resources and violence is on the rise. Nothing spells globalization quite like the all-too-familiar T-shirt with a frowning Che Guevara available for purchase at the foothills of the Himalayas.

Subsequently, the first week’s activities were divided between participatory design work at the Government School for Girls in Leh and field trips to the surrounding villages, where we focused on four thematic areas: Culture and Heritage, Learning Environments, Safety and Sustainability. To facilitate our interaction with the students, Sarah Ernst, one of the workshop coordinators, presented the idea of Participatory Rural Appraisal, an approach meant to involve the local community in the design process by sharing information through mapping of ideas and collaborative discussions. This way we were able to find out details of the students’ life in and outside the school. Tsering Tashi, the Physical Education teacher, explained that most of the students come from faraway villages in Ladakh and they stay with relatives while studying in Leh. We were surprised to find out that during winter, the school is closed for two and a half months, due to the harsh weather. Subsequently, the first week’s activities were divided between participatory design work at the Government School for Girls in Leh and field trips to the surrounding villages, where we focused on four thematic areas: Culture and Heritage, Learning Environments, Safety and Sustainability. To facilitate our interaction with the students, Sarah Ernst, one of the workshop coordinators, presented the idea of Participatory Rural Appraisal, an approach meant to involve the local community in the design process by sharing information through mapping of ideas and collaborative discussions. This way we were able to find out details of the students’ life in and outside the school. Tsering Tashi, the Physical Education teacher, explained that most of the students come from faraway villages in Ladakh and they stay with relatives while studying in Leh. We were surprised to find out that during winter, the school is closed for two and a half months, due to the harsh weather.

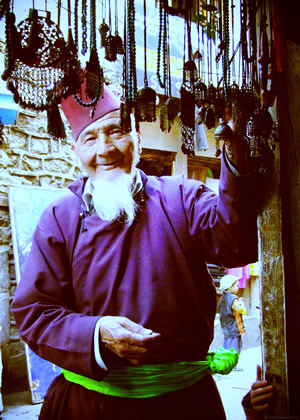

Soon after meeting the girls, we went on a tour of the old town of Leh with Andre Alexander, a specialist in Ladakhi architecture. He gave insight into local traditional building techniques and materials, explaining that Leh has been classified by the Indian Government as a slum due to its lack of a sewage system. Bypassing textile dyeing workshops and shoemakers’ ateliers on the narrow streets of the old town, I was struck by the similarities between the façade of traditional Ladakhi houses and the façade of a cula, a type of fortified house found in the Southern regions of Romania. Even the layout is similar, with the windowless ground floor reserved for storage and keeping animals, and the upper floors with their progressively enlarged windows used as living quarters. However, the construction materials are different. Poplar wood is the main building material in Ladakh, while granite is being used for the foundations and the ground floor, and mud bricks or rammed earth are used for the upper floors. Now, most houses are hybrids as concrete has become an increasingly popular material since the 1970s.

The middle of the week marked my first trip to an Indian hospital. Even though I was in Leh for several days at this point, my body wasn’t dealing with the high altitude very well. Nevertheless, after a jab and a prescription for pills, I was anxious not to miss the trip to the Druk White Lotus School in Shey. Founded at the initiative of His Holiness Gyalwang Drukpa, the school provides education for children from remote areas of Ladakh. Some of the school facilities were damaged during the flash floods that hit the region in August 2010; meanwhile, everything was cleaned up and a retaining wall was erected. The tour around the school grounds was led by Suria Ismail, an engineer from Arup Associates. She explained how the layout of the school – set-up in courtyards – was inspired by the mandala. While walking around the various blocks, we became aware of the major role played by the orientation of the buildings in making the most of the natural light and heat. I was particularly impressed by the modern reinterpretation of the trombe wall incorporated into the residences block. The sun-facing wall was painted black to improve the absorption of solar energy, while the addition of vents to the top and the bottom of the inner wall improved the flow of air into the building.

Despite being set in a high altitude desert, the school strives to be self-sufficient by having solar panels that supply energy and a solar panel water pump. Another impressive feature was the toilets block. Drawing on the traditional compost toilet, suitable for a harsh climate where year-round functioning flush toilets are virtually impossible, the back wall of the composting space is made out of a large sheet of steel painted black. This helps create an updraft that draws the smells out through horizontal vents at the roof level.

While the Druk White Lotus School was a great lesson in sustainability based on traditional and modern solutions, we discovered similar principles implemented at a fraction of the cost at an experimental campus called SECMOL (The Student’s Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh). Located in the Indus valley near Phey, this school admits around 40 students and aims to prepare them for adult life by making them responsible for their surroundings (they take turns preparing meals in the kitchen, maintaining the school grounds and taking care of animals). Moreover, sustainability is taught through playful experiments like the solar cooker (a simple structure made out of mirrors, that can be used to boil water), as well as through a scheme of recycling the waste material produced on site. A low-cost passive solar system has been applied successfully - plastic sheets are used to soak up the sun, only to be rolled over the windows during the winter to keep the buildings warm. While the Druk White Lotus School was a great lesson in sustainability based on traditional and modern solutions, we discovered similar principles implemented at a fraction of the cost at an experimental campus called SECMOL (The Student’s Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh). Located in the Indus valley near Phey, this school admits around 40 students and aims to prepare them for adult life by making them responsible for their surroundings (they take turns preparing meals in the kitchen, maintaining the school grounds and taking care of animals). Moreover, sustainability is taught through playful experiments like the solar cooker (a simple structure made out of mirrors, that can be used to boil water), as well as through a scheme of recycling the waste material produced on site. A low-cost passive solar system has been applied successfully - plastic sheets are used to soak up the sun, only to be rolled over the windows during the winter to keep the buildings warm.

Subsequently, we visited two different types of post-disaster shelters built for the families affected by the August 2010 flash floods. First we stopped at Solar Colony. Despite its whimsical title, the settlement was erected in a barren valley devoid of any type of public facility. Some of the residents were building traditional homes at the time of our visit, complaining about the shortcomings in the design of the shelters provided by the Leh District Administration. Built out of sandwich panels, these shelters were uninhabitable during the harsh winters and showcased a disregard towards the residents’ customs and needs. What we saw at Solar Colony didn’t come as a surprise in light of the presentation on disaster management given by Tara Sharma from INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Culture). Local authorities generated a so-called “disaster economy” by taking advantage of the aid and disregarded the need for a disaster management strategy. Moreover, most of the NGOs that built shelters did not employ architects.

In contrast to Solar Colony, the shelters designed by SEEDS (ASF-UK’s local partner) integrated traditional building materials (mud bricks and wood) and featured trombe walls to keep the buildings warm during the winter. What I liked most about these shelters was the ability given to the residents to expand them in time, according to their needs and resources, as well as the integration of Ladakhi architectural motifs. Overall, these shelters seemed effective in helping the residents overcome the consequences of the floods. In contrast to Solar Colony, the shelters designed by SEEDS (ASF-UK’s local partner) integrated traditional building materials (mud bricks and wood) and featured trombe walls to keep the buildings warm during the winter. What I liked most about these shelters was the ability given to the residents to expand them in time, according to their needs and resources, as well as the integration of Ladakhi architectural motifs. Overall, these shelters seemed effective in helping the residents overcome the consequences of the floods.

Week 2: Design & build

On the second week of the workshop, we started to work effectively at the Government School for Girls in Leh. First, we were divided into three groups. Drawing on what we learned in the previous week, each group had to develop proposals for the school with different time frames for implementation:

As part of the short term group, me and my team mates started work by selecting a site on the school’s grounds for our proposal. We decided on a site in the proximity of the library, considering the request of the students for a reading space in the courtyard. Equally important in deciding on this site was its perspective towards the playing field and the presence of a small bed of flowers, a rarity in the school’s courtyard.

After a series of intense charrettes, we based our design proposal around a central wall of varying heights with incorporated seats, meant to offer privacy to the girls. An important feature of the seating area was the canopy built out of willow sticks, a reference to the roof structure of traditional Ladakhi houses. Our choice of materials was driven by the desire to make a sustainable project. Thus, we employed harvest mapping to identify local materials and resources in the area surrounding the site. The procurement of materials took a couple of days and one of the most exciting moments was when all the participants formed a chain to help unload 220 mud bricks from a truck. Simultaneously, we did rammed-earth tests, but this technique has proven its inefficiency due to a lack of proper materials, as well as our limited construction schedule. Another goal of our project was to show students how various objects can be reused, by incorporating recycled glass bottles into the mud brick wall. After a series of intense charrettes, we based our design proposal around a central wall of varying heights with incorporated seats, meant to offer privacy to the girls. An important feature of the seating area was the canopy built out of willow sticks, a reference to the roof structure of traditional Ladakhi houses. Our choice of materials was driven by the desire to make a sustainable project. Thus, we employed harvest mapping to identify local materials and resources in the area surrounding the site. The procurement of materials took a couple of days and one of the most exciting moments was when all the participants formed a chain to help unload 220 mud bricks from a truck. Simultaneously, we did rammed-earth tests, but this technique has proven its inefficiency due to a lack of proper materials, as well as our limited construction schedule. Another goal of our project was to show students how various objects can be reused, by incorporating recycled glass bottles into the mud brick wall.  During the last three days of the workshop, everybody contributed to the construction process by helping with cutting and nailing the willow sticks for the canopy or laying bricks. The workshop concluded with a presentation of all the projects developed by the three teams in front of an audience comprised of students, the local community and our collaborators. During the last three days of the workshop, everybody contributed to the construction process by helping with cutting and nailing the willow sticks for the canopy or laying bricks. The workshop concluded with a presentation of all the projects developed by the three teams in front of an audience comprised of students, the local community and our collaborators.

Exploring Chandigarh, Jaipur and New Delhi

After the workshop in Leh, my Berkeley Travel Fellowship continued with visits to three important Indian cities: Chandigarh, Jaipur and New Delhi.

I reached Chandigarh after a four hours train ride on the Kalka Express from New Delhi. Once I stepped out of the train station, my preconceived idea of what a city should look like was dismantled while facing a seemingly endless mass of vegetation, with no buildings in sight. The contrast with the bare landscape surrounding Leh couldn’t have been bigger. My first impression of the city as a sprawling forest with tarmac covered roads increased on the taxi ride to the Chandigarh College of Architecture. Despite the heavy car traffic, there was hardly anyone on the sidewalks and the buildings were concealed by greenery and fences. At the college, I had the privilege of meeting Mr. J. P. Singh, the dean of the school, who led me on a tour of the studios and advised me on how to make the most of my short time in the city. Despite being met with knowledgeable smiles when I expressed the desire to explore the city on foot to get a better sense of its atmosphere, I walked from the college to the Chandigarh City Museum.

Following the grid comprised of fast traffic roads that separates the city’s 56 sectors, orientation for pedestrians can be confusing at times as there are no visible landmarks (except for signs when you pass from one sector to the next). The visit to the museum was an opportunity to learn more about the city’s history and to see original drawings and photographs documenting the different planning stages of Chandigarh. Built as a consequence of India’s Partition in 1947 as an administrative capital for the states of Punjab and Haryana, the city was meant to embody the country’s shift towards progressive development. The ground floor of the museum is dedicated to the initial planning processes, displaying the drawings of the American urban planner Albert Mayer and Matthew Nowicki, the chief architect of the city. In his master plan proposal for Chandigarh, Mayer drew on the principles of the Garden City Movement, dividing the city into superblocks (units with basic amenities) and devising a circulation system sensitive to the gentle slope of the site. The upper floors exhibit the work of the team led by Le Corbusier, who was employed as Architectural Adviser in 1950, after the death of Nowicki. Even though he was hired to design the Capitol buildings and assist the implementation of Mayer’s plan, Le Corbusier took the opportunity to see his ideas of segregation between living, working, circulation and leisure areas materialized. He revised Mayer’s plan by laying an orthogonal grid on top of the circulation scheme and transforming the superblock into 800x1200 meters sectors. Nevertheless, Le Corbusier’s greatest mark on the city is represented by the Capitol Complex, a series of government buildings. Following the grid comprised of fast traffic roads that separates the city’s 56 sectors, orientation for pedestrians can be confusing at times as there are no visible landmarks (except for signs when you pass from one sector to the next). The visit to the museum was an opportunity to learn more about the city’s history and to see original drawings and photographs documenting the different planning stages of Chandigarh. Built as a consequence of India’s Partition in 1947 as an administrative capital for the states of Punjab and Haryana, the city was meant to embody the country’s shift towards progressive development. The ground floor of the museum is dedicated to the initial planning processes, displaying the drawings of the American urban planner Albert Mayer and Matthew Nowicki, the chief architect of the city. In his master plan proposal for Chandigarh, Mayer drew on the principles of the Garden City Movement, dividing the city into superblocks (units with basic amenities) and devising a circulation system sensitive to the gentle slope of the site. The upper floors exhibit the work of the team led by Le Corbusier, who was employed as Architectural Adviser in 1950, after the death of Nowicki. Even though he was hired to design the Capitol buildings and assist the implementation of Mayer’s plan, Le Corbusier took the opportunity to see his ideas of segregation between living, working, circulation and leisure areas materialized. He revised Mayer’s plan by laying an orthogonal grid on top of the circulation scheme and transforming the superblock into 800x1200 meters sectors. Nevertheless, Le Corbusier’s greatest mark on the city is represented by the Capitol Complex, a series of government buildings.  I spent the second day in the city attempting to visit the Capitol Complex, an endeavor which proved difficult at times due to the strict security regulations. Escorted by a soldier, I was allowed to spend 15 minutes on the terrace atop the Secretariat building. From this point of the view, the introverted nature of the Capitol Complex became apparent, as an all-engulfing mass of vegetation separated it from the city. William Curtis’s observation of the Capitol’s appearance as a “grave and dignified ruin” rang true. To the left of the Secretariat, the imposing tower atop the Assembly was projected against the Shivalik Hills. On my way back, I had the opportunity to experience for a short while the atmosphere of the building. Le Corbusier’s architectural approach to India’s climate has been put into question over the years. Inside the Secretariat, the humidity brought by the monsoon was unbearable and I noticed what looked like a recent addition: fans attached to the walls to help remove heat. I spent the second day in the city attempting to visit the Capitol Complex, an endeavor which proved difficult at times due to the strict security regulations. Escorted by a soldier, I was allowed to spend 15 minutes on the terrace atop the Secretariat building. From this point of the view, the introverted nature of the Capitol Complex became apparent, as an all-engulfing mass of vegetation separated it from the city. William Curtis’s observation of the Capitol’s appearance as a “grave and dignified ruin” rang true. To the left of the Secretariat, the imposing tower atop the Assembly was projected against the Shivalik Hills. On my way back, I had the opportunity to experience for a short while the atmosphere of the building. Le Corbusier’s architectural approach to India’s climate has been put into question over the years. Inside the Secretariat, the humidity brought by the monsoon was unbearable and I noticed what looked like a recent addition: fans attached to the walls to help remove heat.  Next, I visited the High Court after being denied access to the Assembly. Preceded by a vast esplanade punctuated with wisps of grass, the High Court’s proportions seemed less intimidating in comparison to the Secretariat’s monumentality. Nevertheless, the sculptural character of the double roof was impressive, as well as the concrete brise-soleil on the main façade. My favorite architectural feature was the open ramp leading to the top level of the floor, wrapped around a perforated wall that allows glimpses towards the Assembly Hall and the Secretariat. Next, I visited the High Court after being denied access to the Assembly. Preceded by a vast esplanade punctuated with wisps of grass, the High Court’s proportions seemed less intimidating in comparison to the Secretariat’s monumentality. Nevertheless, the sculptural character of the double roof was impressive, as well as the concrete brise-soleil on the main façade. My favorite architectural feature was the open ramp leading to the top level of the floor, wrapped around a perforated wall that allows glimpses towards the Assembly Hall and the Secretariat.

In contrast to the stilted atmosphere of the Capitol, the commercial area in Sector 17 seemed lively. People were shopping, talking walks or relaxing. Nevertheless, as the evening approached, some of the open plazas were barely lit and became quickly deserted.

Chandigarh intrigued me, but the time that I spent in the city was too short to judge its urban qualities. I would like to come back to explore its limits and the way the city accommodates its increasing population, beyond the initial planned scheme and Le Corbusier’s prescriptions.

Subsequently, I visited Jaipur, the 18th century walled city built by Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II. As the historical city’s layout was inspired by a nine-part mandala, a grid of avenues divides the city into nine sectors. It was interesting to notice how, in contrast to Chandigarh’s typical sector, the commercial areas are disposed along the main streets, protecting the residential areas nestled in the middle of the block. From the main streets, alleyways provide access to multistoried residences called havelis, typically organized around one or multiple courtyards. Consequently, this has generated a vibrant urban atmosphere, as well as a gradual transition from the public areas towards private space.

Jaipur’s center is dominated by the presence of maharaja’s residence, City Palace, occupying two of the city’s blocks. While the palace can be visited only by tourists, a network of public spaces placed at strategic points plays an important part in the city’s dynamic. On the whole, despite being overcrowded and lacking Chandigarh’s detailed landscaping, Jaipur’s mix of functions seemed to foster and generate a better urban life. Jaipur’s center is dominated by the presence of maharaja’s residence, City Palace, occupying two of the city’s blocks. While the palace can be visited only by tourists, a network of public spaces placed at strategic points plays an important part in the city’s dynamic. On the whole, despite being overcrowded and lacking Chandigarh’s detailed landscaping, Jaipur’s mix of functions seemed to foster and generate a better urban life.

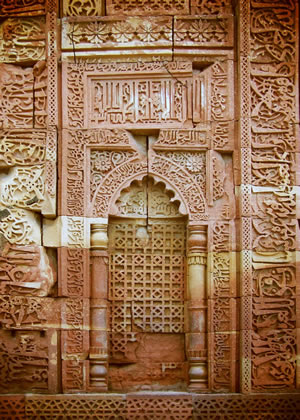

Finally, my last stop was in New Delhi. After having to change my plans of visiting the part of the city designed by Edward Lutyens, I visited Qutb Complex, a group of Islamic monuments located in Mehrauli, one of the seven ancient cities comprised in contemporary Delhi. The oldest monuments of the complex date back to the 12th century, marking the beginning of Muslim rule in India. One of these monuments is Qutb Minar, a five stories-high tower showcasing Indo-Islamic architectural motifs. The different stages of construction are highlighted by the use of different type of materials, with red and buff sandstone being used for the first three stories, while the last two were built out of marble. In fact, red sandstone was the preferred building material for the rest of the complex’s monuments.

Being a Berkeley Travel Fellow was an extraordinary experience as it gave me the opportunity to experience and observe the social dimensions of architecture in a variety of settings. I am particularly grateful for what I learned during the workshop in Leh, which I hope to apply successfully for the betterment of the communities in my country.

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|