Saavi Natekar and Ayesha de Sousa - EssayTHE ARCHITECTURE OF THE PEOPLE: CONTEMPORARY INDIA’S QUIET REBELLIONURBAN INEQUALITIES

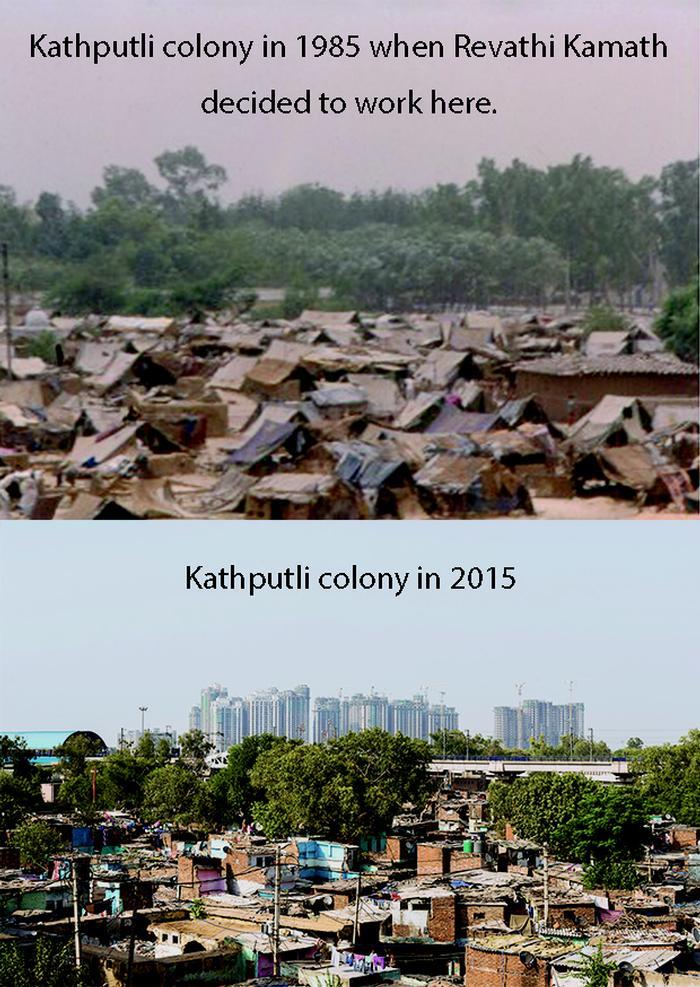

As one views the streets of the great Indian metropolis, one is awestruck by the soaring skyscrapers with their glass facades, gleaming in the sun like the promises of modernity. Less noticeable are the scattered settlements of migrant labourers all over the city – a collage of cancerous asbestos propped up with poles, with a sheet over their heads if they are lucky. The settlements of construction labourers flank the soaring skyscrapers that taunt them – built by their hands, but far from their reach. The daily exposure to this sight has rendered the juxtaposition a collective blind spot, with the slums fading into the shadows, unaddressed and unaccounted for. Urban India exists as a jarring confluence of the privileged who run the city and those invisibles who keep the city running.

While the country has experienced positive economic growth at the state and district levels since the liberalisation of the economy in 1991, the experience on the ground tells a different story. India’s growth has been biased; its development fraught with inequality - both, in quality and in quantity of per capita space. This distinction has reinforced the mentality that money predetermines the right to adequate, healthy space.

Animated by the spirit of burgeoning development, architects are thrust into a model of aspiration- driven by the need to be known, to be seen and to leave a visible legacy. In such a socio-economic climate, few projects dare to confront the ordinary. In a country of rampant spatial inequality, addressing the ordinary worker or the child in the slum assumes the proportions of an act of rebellion. The projects that truly embody the social art of architecture are those that are intrinsic to, and inextricable from the community that they serve- those that leave the user empowered and uplifted.

The architect chooses to be anonymous by sacrificing their own identity and visibility for those of the community. Their eyes see the city’s ‘invisibles’, carving out a space for their social identification and belonging in a society that profits from division. They work with limited resources, moulding and rearranging the fabric of the existing landscape, by treating every decision with dignity. The intentions of the architect encompass understanding and upliftment from the start of the process to its end; from the arms that build, to the eyes that see, to the tiny feet that play.

OUT OF THE SHADOWS

“Gujarat: At least 15 migrant workers crushed to death by truck in Surat”

This accident took place on January 19, 2021 when workers, looking for a place to sleep, saw no alternative but a footpath. Such workers flock to cities in search of employment, and most end up living hand to mouth with little financial security. In 1979, the Inter-State Migrant Workmen Act enforced the provision of basic infrastructure to improve the standard of living of the migrant workforce. The predicament of workers, particularly in the construction industry is perilous, as no employer would invest in infrastructure that is demolished on the completion of every project. Policies have continued to push for better living conditions, yet four decades following the legitimization of the migrant workforce, about a third of the Indian population continues to remain vulnerable.

A house implies belonging, but what houses those who do not ‘belong’? Migrant labourers not only suffer from financial vulnerability but also from ill-health and poor living conditions. In 2016, Nebula Infraspace LLP, a real estate developer in Ahmedabad, pledged to provide affordable housing for its workforce through the Avaas project. The project sought to meet the holistic needs of every employee and their family, including healthcare, schooling, and skill development.

The architectural team behind this project was New Zealand-based Hatch Workshop. Principal architect, Hannah Broatch had conducted a detailed study of Ahmedabad’s squatter settlements as part of her Masters thesis. Through her study, she observed that every wall, partition, and stone laid in a squatter colony was backed by conscious thought, and every piece of land and material was carefully used. In a typical settlement, most household activities, from cooking to bathing, take place outside the envelope of the home, which is often too small and heated to be inhabited during the day. This results in extremely vibrant and multifaceted semi-private niches between the units where the community interacts. However, these can be hazardous as they pose a major fire hazard, and breed disease in the absence of any drainage system.

The original settlement of metal sheet sheds formed the basis of the design of the housing units. Respecting the workers’ natural way of life, the architects proposed a module of 3m x 3m, derived from the dimensions of the sheds. Wall panels were fixed between bamboo poles, and raised roofs were inclined to facilitate natural light and ventilation. Each unit was linked to an otla or semi-open space, for functions such as cooking and drying clothes. Various combinations of these units form clusters, each enveloping a larger otla. This retention of unbuilt space allows for personalization of the space, while retaining a sense of community. Multiple clusters surround a community creche and a playground,providing natural surveillance while parents work. The ground is gently sloped to facilitate the drainage with toilet blocks placed at the periphery.

It was a challenge to build a sense of home for a community that led a nomadic life, shifting base at the end of every project. This transience was reflected in the design of Aavas, which could be dismantled in its entirety, and moved to a new site, leaving a plinth as the only evidence of its habitation.

BUILDING FUTURES

“From little things, big things grow.”

This philosophy rings true for The Anganwadi Project (TAP) in more ways than one. Since 2007, the organization, in partnership with Manav Sadhana, an NGO, has built eighteen anganwadis for underprivileged children living in slums in Ahmedabad and Andhra Pradesh.The anganwadis, which are all low-cost sustainable spaces, are built in consultation with the community and in part, by them. They provide a safe and nurturing pre-school environment, as well as daily meals to children belonging to underprivileged communities. Anganwadis often double as community centres after hours for the education of teenage girls whose schooling is largely neglected.

For most architects, a room of 3m x 4m would not be the subject of intense debate, but for Harshil Parekh, the story was far different. An alumnus of CEPT University, Ahmedabad, Harshil was pursuing his final year research thesis when he volunteered for the project - a decision which would significantly impact his relationship with the profession.

The anganwadi in question, Bholu 14, is a humble bamboo structure located in the Gandhi Vas area of Sabarmati. This anganwadi was built following intense discussion and community involvement- a process that has been honed by TAP over time. According to Harshil, the most fundamental part of the six-month process was the first few weeks, during which the volunteer architects sought to build a relationship with, and develop a clear understanding of the community. While working with experts foreign to the less privileged context, there was always a measure of distrust that had to be overcome due to the discrimination faced by the community in the past. In this respect, the teacher of the anganwadi acted as a mediator, and cleared the way for the design process.

The uniqueness of TAP is that it throws the architect out of their comfort zone, forcing them to confront the ground reality of construction with limited resources. In the case of Bholu 14, the site came with its own challenges. Open on three sides with a neem tree at the north end, the site was filled with construction debris. Bearing this in mind, the architects proposed a lightweight bamboo structure, a material that was locally available in Ahmedabad. This choice of material allowed for the entire anganwadi to be dismantled and relocated in the event of the land being reclaimed by the government.

To start with, the volunteer architects conducted a thorough site analysis and discussed the needs and spatial requirements of the anganwadi with the community. Soon enough, the question arose– how would an architect communicate a design to a community to which architectural drawings were alien? Here, the architects relied on physical models of the proposal- creating multiple iterations, all with an emphasis on natural light and ventilation. Only with the feedback of the community did the construction of the anganwadi begin.

The final result speaks volumes of the architects’ dedication to the participatory process. Bholu 14 is a room of 3m x 4m, but it has all that a child could ask for. In the dry heat of Ahmedabad, the structure ventilates through porous walls and a roof slant that brings light into the space. Its bamboo envelope provides the students with a balance of privacy and outdoor connection.Through floor-to-ceiling doors, the anganwadi effects a seamless transition into the courtyard, which enables classes to spill over into the shade of the existing neem tree. The blackboard, too, was designed to be portable to facilitate outdoor learning. On the Southern side, the design incorporates a brick wall with a kitchenette and built-in cabinets. This wall provides the requisite thermal mass to counteract the harsh southern sun and gives the interior privacy from the street.

The success of Bholu 14, though, lies in the attention to detail. Every design element was the subject of community discussion and arose from engaging with issues at the human scale. Once the shell had been built, the floor was finished in a mosaic of broken tiles-by tying together the broken pieces into playful patterns for the children to enjoy. The courtyard was finished in kota stone, donated by the community, and the boundary walls were made out of a series of connected mesh cylinders, filled with brickbats and recycled stones collected near the site. Since the demand for additional water did not support adding planters, the courtyard was instead painted with colorful plants and animals, to create an engaging environment.

“When working with TAP, there is no concept of authorship of the architect- the author is the community itself and it is they who own the space by inhabiting it.” For someone in a profession obsessed with a legacy, Harshil’s candour is refreshing. In his own words, “The difference is in the approach. When most projects place the architect as the centre of the process as the expert, in TAP the goal is to break that hierarchy. We say to the community, ‘I know some things, and you know others-let us share our knowledge and do it together.’ That is what truly empowers the community and encourages their enthusiastic participation in the building process.” With this, he touches upon a key element of the social design process, painting the architect as a mediator of technical expertise rather than as an author of their own concept. In TAP, the architect’s role is to enable and to work with the community to build for themselves through discussion and understanding. In this way, the act of co-creation becomes an act of healing, sowing the seed for a brighter future.

TAP is also a remarkable example for the architectural community as the triumphs and pitfalls of every anganwadi are openly acknowledged and studied post-completion. Thus, each project, rich with its own nuance becomes a precedent for the next - both in terms of the process and of the end product. As Harshil says, “When intervening in such contexts, even with the best intentions, one can make mistakes. TAP’s model ensures that no one makes a mistake that has been made before. We only make new mistakes.”

BRIDGING THE GAP

Buildings are often described as ‘works of an architect’, inherently tied to their own identity. For an impressionable aspirant, it is easy to confuse the expression of the architect with the merit of the design and its appropriateness to its purpose. The education system plays an essential role - guiding the student to make this distinction. While the system of architectural education in India lays emphasis on technical expertise and critical thinking, it belies a disconnect with the common people. Over the course of five years, the student develops ideas and interests, albeit rarely questioning their own intentions. While students participate in basic design tasks and build observational skills, more time could be devoted to interaction with those outside the architectural fraternity. This would effectively broaden the horizons of students, acquainting them with the ground realities of dealing with communities, especially those with limited resources.

Architecture ought to be introduced to students not merely as a creative, but as a collaborative act. Schools of architecture would do well to capitalize on the open-source movement. Like the work of Aravena’s Elemental and the sequential learning of TAP, there lies an opportunity for students to engage with the work of their peers beyond mere social interaction. A feedback mechanism could be promoted through forums, exhibitions and debates which involve students as well as the community at large. The goal of this model would be to break the existing hierarchy between the profession and the society beyond the top ten percent. The integration of feedback and user interaction would be a valuable addition to students’ projects, sensitizing them to the needs of the common people as they navigate the art of relationship-building, and develop an intrinsic sense of social sensibility.

In a system that glamorizes the architect as an artist, the desire to stand out among fellow students exaggerates personal identity and voice. Within this framework, the social implications of student projects often fall beyond the purview of discussion.

The past year has exposed the stark inequalities that characterize our landscape. The celebration of self-expression within the profession has put the architect on a pedestal overshadowing the people, much like the skyscraper with the slum at its feet. The architecture of the people launches a quiet rebellion against this gigantism in an efficient yet playful way, questioning it, “How much achieved, how many impacted, how many less harmed with so much less?”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Broatch, H (2015) Housing For Construction Workers in Ahmedabad, India. retrieved from https://unitec.researchbank.ac.nz/handle/10652/2899

‘Housing for Construction Workers in Ahmedabad’ Archiprix International, 2007. retrieved from https://vimeo.com/210280955

Parekh, H. (2021, October 26), Personal interview

Rothschild J. (2020, 21 Dec), The Anganwadi Project, Glass Half Full. retrieved from

https://www.designdotstory.com/post/glass-half-full-jane-rothschild-the-anganwadi-project

The Anganwadi Project,Bholu 14 (2017), Project Details. retrieved from https://www.anganwadiproject.com/bholu-14

‘Truck Runs Over 15 Migrant Workers Near Surat While They Were Asleep’,The Outlook 19 January 2021. retrieved from https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/gujarat-accident-truck-runs-over-15-migrant-workers-killing-while-they-were-asleep-at-roadside/371060

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |