[ID:78] Archie Bray: Sacred Creation of Past and PresentUnited States I am far enough away from the main structure that I see the Archie Bray in its entirety. The first shapes to catch my eye are the high towers, rectilinear brick forms like chimneys left standing after the rest of the house has fallen away. They rise intermittently, each a replica of the last scattered among the various buildings. As I move closer, the essence of the Archie Bray begins to reveal itself. Breaking through the curtain of snow are the warm reds and browns of weathered bricks, the frayed whitewash of old wood and the patina of rust against the cloudless Montana sky. In the recesses of a brick wall, tiny ceramic cups have been placed like blue specks on a terra cotta canvas. The earth in front of me is uneven as if wind pushed the snow around depositing it unevenly to rest in mounds. Where the peak of each bulge breaks through the crust of snow, what is revealed is not earth. It is not tufts of grass or mounds of dirt but a garden of pottery. The lips of vessels and edges of sculptures erupt through the blanket of white as the first shoots of newly planted seeds. In the space between these gardens, the pathway is intimated, a simple crust of snow broken by footsteps. Today there is no one. I am alone to amble and discover the infinite moments of creation peppered throughout the grounds.

The Archie Bray Foundation for the Ceramic Arts in Helena, Montana is a sacred space where the past and present exist simultaneously inviting reflection, inspiration, and creativity. The Bray started as a brick foundry but for fifty-eight years it has seen new life as a ceramic institution where resident artists can further explore their craft. In addition, the Archie Bray is a place of public significance. The grounds are open to the public, classes are offered to the community, artists create flower pots for mother’s day, exhibitions open and close throughout the year and at the annual Brickyard Bash lovers, supporters and the curious come to celebrate the place and the people who care for it. The Archie Bray Foundation is especially sacred to me because I was married on the grounds, surrounded by structures of the past and present and the ceramics left by artists; echoes of what this place has meant to those who have come before me.

A sacred space is a place where individuals sense history, see the beauty of the present, and are inspired towards the future. Sacred spaces are alive and transformative. Beauty reveals itself as the cycles of simultaneous decay and rebirth move through and around them. The sanctity of the Archie Bray is multi-faceted. The story of Helena is alive in the grounds of the Bray and the grounds encompass the history of ceramic arts and the power of the craft. Materials reference the beginnings of the West and the agricultural history of the region that is slowly fading away. Intertwined is a more recent history in which the production of fired ceramics evolved from a strictly utilitarian endeavor to a fine art. This unique place has drawn gifted ceramicists from around the globe who by their very presence in this place participate both in the in the history of the West and of their craft.

The community of Helena has the unique opportunity to experience this sacred space, learn from world-class ceramicists, and be exposed to the power and the diversity of art. The Archie Bray is set apart from other foundations because it combines so many quintessential elements and offers a unique experience for both the artists and the community.

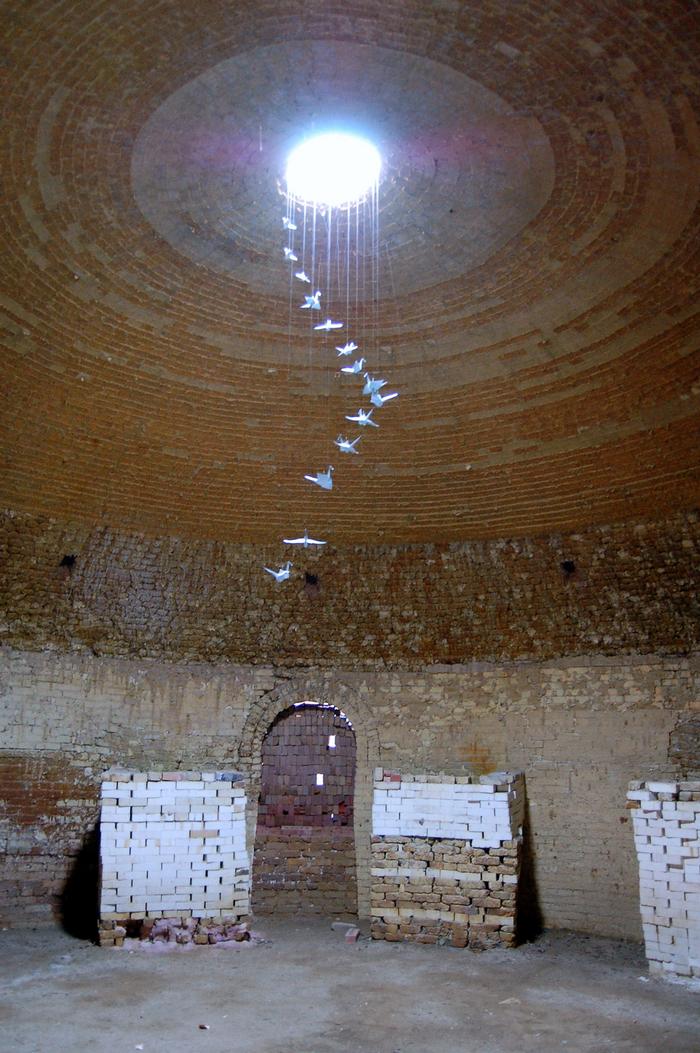

The earliest creations still present on the ground are not pieces of artistic expression but components created for a utilitarian purpose: bricks. The Archie Bray started as a brickyard named the Western Clay Manufacturing Company. In fields beyond its structures lie piles of old bricks, siblings of those used to build the town and line the streets of Helena. Often they are incorporated into new works in the ongoing cycle of renewed life at the Archie Bray. Among the ceramics, remnants lie beside newly crafted pieces. The entire spectrum of life is present here. Aging pieces, their cracks collecting moisture and earth stand beside others that weathered the seasons more gracefully but whose age is apparent in their subdued tones, their glazes mellowed by years of sunlight. There remains a strong connection between clay arts and the architecture around it. Kilns are used for firing both utilitarian ceramics such as bricks as well as cups, pots, and sculptures. These large ovens that fire the clay for hours become part of the architecture surrounding this craft and an essential element in finalizing the product. Among the buildings on the grounds of the Bray are the beehive kilns, a series of brick domes used for firing bricks when the Western Clay Manufacturing Company was still in business. Entering the beehive kilns, it is apparent that they are no longer in use. Tufts of grass push through the packed earth and the scars from old fires are still visible on the faces of the bricks. An oculus, a circular opening in the dome, looms overhead and harkens images of the pantheon in Rome on a small scale. From it, a flock of ceramic origami swans descend. The old and the new mix again.

This evolution is also present in the architecture of the Bray. The aging beehive kilns blur the line between art and architecture. They stand beside a new structure. The clean edges of newly laid brick stand against the crumbled corner of a tower. The corrugated metal roof of the new studio picks up where the roofline of the foundry falls away. Its steel still corrugated, though now it is rich dark brown, contrasts beautifully with the glint of the new steel. They stand as neighbors, pieces of the same system yet the purpose of each structure evokes a unique feeling. The old structures create context for the new ones and completion of the new structures free the old to become beautiful in their age and form. Fallen towers rest upon the remaining fibers of one roof as massive balancing sculptures. The bubble-like ceilings of the domes contrast the angular form of a new building, a studio space, as it rises beside a structure from the days of the brick foundry. Still, the new buildings acknowledge the history of the space through their use of wood, brick and steel. Their forms reflect the form of the original structure now transformed with age. The graceful transformation challenges the barrier between structure and sculpture but secures the connection between art and architecture.

There are currently limited educational facilities at the Archie Bray. A number of small buildings from the original clay business are being used as classrooms. A conscientious and contextual design of classroom facilities will bridge the gap between the community and the artists at the Bray by allowing more teaching to occur and most importantly, to allow people in the community more use of the facilities as they learn the craft of fine art ceramics. Through this increased classroom space, the number of people becoming a part of the story of the Archie Bray will increase and their connection with the foundation will strengthen. This is the essential architectural intervention at the Bray. Development of educational facilities on the grounds would bring more people to the Archie Bray as students, instill the importance of art throughout the community, and provide an opportunity for the community to experience all the sacred elements the foundation has to offer.

Within the history of the Bray there has been continuous intervention, artistic and architectural, though I prefer to speak to these as moments of artistic and architectural deflection. Both are integral parts of the evolution of the space and as much a part of the Bray’s sanctity as the first steps taken on this ground and the first thoughts about its creation. Continuing on, more art will be created and new structure will rise. This is our current moment of deflection, an opportunity and a test of our integrity. Just as philosophy, history, individuality, and social awareness go into each ceramic work created at the Bray, the same must go into every structure erected there. While I believe it is absolutely necessary to expand the reach of the Foundation through improved educational facilities, the importance of this decision and the implications of the design are crucial to the continuation of the sanctity of the Archie Bray. Conversely, the social implications of creating new space at the Foundation in the spirit of the current site and conserving the sanctity of the space will be profound. This social architecture, available to a larger number of people, will highlight the benefits of such decisions and encourage well-designed, thought out creation in the future and will showcase the value of design as it relates to other venues around the region.

The design focus for the educational facilities at the Bray should be materiality, form, and function. The materials of the structure are obvious. In all the buildings at the Bray, there is a simple utilitarian elegance. From the oldest warehouses to the newest studio space, brick, timber, and steel combine like variations on a modern farm shed. They are beautiful because they are simple and because they still project their functionality. New structures must do the same. The new educational facilities will greet every visitor entering the grounds. With a new structure, there is the opportunity to embrace aspects of the Archie Bray that are currently underemphasized. The new buildings must embody that which lies at the heart of the Bray. They must project utilitarian minimalism with their timeless use of materials and their tall slender form. They must also encompass the sanctity of the grounds. They must invite learners to create within them and intrigue the visitor as if the studio alone could be the work of art they came to see. The combination of peaceful assimilation into the sacred grounds and subtle intellectual challenge is at the heart of the design process. The opportunity is here to create a new sacred space within the larger sweep of the Archie Bray Foundation.

Undoubtedly, the artists and the board have the spirit of the Archie Bray in mind as they converse about the upcoming evolution of the space and the way it will merge with the continuing cycle of renewal on the grounds. The same architects designed the most recent structure built and each of them understands the sanctity of the space and the importance of their work. The community is the next step. Moving forward, this incredible resource opened to all will touch more lives. With increased involvement from the community, the artists, and the board new generations will become involved such integral pieces of the past and present, moving toward an inspired, creative future.

The Archie Bray is a sacred space because it invites all visitors to explore the grounds and to experience the history of the art, the story of the region, and intertwining path connecting them. The Bray is a place to reflect as well as a place to rejoice. Its power lies in its sublimity and its familiarity. The Archie Bray allows anyone who visits the sacred experience of grounding introspection and an awareness of the role history and art plays in the human spirit. Increased exposure and recognition of the Archie Bray as a sacred space is key to its survival as a center for the arts and as a talisman for the history of Helena.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |