[ID:4886] Sab-ki Mandi: Enhancing the Markets of India as an Inclusive Public Space for the ElderlyIndia “Aloo le lo, Pyaaz le lo, Sabji le lo!”

“Matar kitne rupay kilo?”

“Sahi daam lagao bhaiya”

(“Get potatoes, get onions, buy vegetables!”

“How much for 1 Kilo peas?”

“Tell the right price, brother”)

The shouts of vendors

The sounds of bargaining,

The smells of the market,

The colors of vegetables,

One Mandi, and you find it all.

The Known:

Someone is here to buy vegetables for tonight's dinner, while another is here to buy supplies for the whole week. Someone only wants to check the prices while the other just came on a whim and will return with bags of vegetables. A Mandi has never been bounded by age, gender, class, or race. As one enters the market, they are greeted with the smell of fresh vegetables and are instantly surrounded by a variety of colors and shouts of vendors. Behind these colorful displays, there is a line of vendors who have been sitting on that brisk ground since morning. Shouting and hollering about every price reduction and quality update, each vendor’s goal is to entice as many customers as possible. Even those visitors who are easily annoyed by the slightest noise become focused to get the best deal. The true struggle begins when one decides to shop while standing amidst the chaos. Walking against the waves of crowd to reach the preferred stall, then bending or sitting on the ground to select the best of the greens, after all, every purchase must be thoroughly checked using all of one's senses. In the meantime, anyone can jump the turns to pay or weigh their own selection and in that smallest moment, one learns the true meaning of tolerance. From here, with newfound fervor, the rounds of bargaining begin. Carrying the heavy bags of vegetables and exiting the Mandi is also not an easy task.

Mandi is a place where chaos becomes its beauty; mostly an informal arrangement of vendors selling a variety of fruits and vegetables laid out on plastic mats on the ground. It is an indispensable experience of growing up in most Indian households. From getting fascinated by the colorful tapestry of vegetables as a kid, to a teenager who starts to understand the humbling Mandi experience, one grows into an adult who, now, visits Mandi with the purpose and responsibility of getting household essentials. As life goes on, it becomes imbibed in one’s lifestyle. For the elderly who have grown up experiencing this, Mandi is one of the most regular places to visit, whether it be with their grandchildren, narrating stories or alone, ready to bargain and enjoy a little chat with the vendors. Nevertheless, these Mandis are not free from challenges, which often go unnoticed and the public bargains their comfort for their necessities; but in such a dynamic environment, a change suited to the needs of all those who use it is both necessary and attainable.

The Potential:

In the urbanscape of India, a Mandi is not just a one-stop hub for fruits and vegetables at affordable prices, but also a type of Public Open Space (POS), with a social and cultural significance associated with it. A POS is an essential component of a city that improves the overall quality of life. It is considered a crucial public health asset contributing tremendously to people's physical, social, and psychological well-being. A Mandi encompasses all three attributes seamlessly; as it promotes physical exercise in the forms of walking; social and mental wellness as it leads to new and curious social interactions. These help in establishing a sense of community and belongingness in the usually fast-paced metropolitan setting. Mandi, thus, serves as a quintessential example of a POS which needs to be used, enjoyed and experienced by everyone.

Designing and developing such spaces as elderly-friendly becomes an immediate need of the country due to the fast-growing elderly population (aged 60 and above), which is projected to increase by 41% and reach 194 million by 2031 (National Statistical Office, 2021). Consequently, to ensure a decent quality of life for the elderly in the near future, planning for it must begin today. One way to do this is to promote active ageing through suitable POSs. Visiting such places to accomplish small tasks like shopping on their own can serve as a huge boost of self-esteem and happiness for them.

Empirical research on the needs of the elderly has shown that with such spaces, regular social interactions can lead to fewer depressive symptoms and a sense of independence, which is often lost as one age and public places become more inaccessible. Furthermore, for the elderly, along with the physicality of the built environment, the personal experience achieved through a social sense of reciprocity between various social features also matters. As a POS, a Mandi in any neighbourhood provides a sense of belongingness to all elderly who have grown up with it. Thus, making the Mandis of India more accessible through inclusive design can lead to an inclusive public space for all.

The Experiences:

The simplest way to begin designing this proposal was to ask the elderly themselves; about their experience, challenges, and even some advice from their daily lives. Our proposal is largely guided by the ground realities that we covered in two rounds of interviews. The concept found its inception in a series of qualitative interviews with 30 elders, who discussed their preference for regular shopping in Mandi, and how it has now become a difficult activity that, in their opinion, was one of the easiest in their younger days. The physical challenges that they now face, have psychological impacts significantly affecting their social and individual well-being. This made us realize how important it was to look at Mandi through a lens of inclusive urban design. Furthering our efforts, two Mandis were selected from the city of New Delhi and being members of its local community, it was easier to conduct in-depth research and interviews.

The growth pattern of these Mandis was one of the determining elements in their selection. The first was spread out across a large area, growing organically; it was more informal with vendors seated on mats strung out in a crisscross pattern of walkways. With people strolling in every direction, the area was so congested that even pausing for a few minutes was impossible. The height disparity between the stalls and the customers made it hard to choose, check, and purchase any product, yet we saw people struggling and continuing to buy. In contrast to this Mandi, the other had a more linear pattern with stalls on both sides of a road. This type of growth encouraged an easier way for the public to traverse but also increased vehicular movement, which created a safety hazard. The sellers had built temporary seating arrangements for themselves, but the issue of the height of vegetables for the customers still persisted. The two Mandis differed vastly in their location, context, spatial layout, people and even in some selection of vegetables yet they were similar in their essence, character, vibrancy and even problems.

Standing amidst the chaos of those Mandis, we conducted more informal interviews with the elderly, both buyers and sellers. The problems that were highlighted across the interviews were encapsulated in a few excerpts quoted ahead in their original language.

“Dikkatein toh kafi hai, lekin sabse zyada toh bheed mein chalne aur raasta dhundne me aati hai. Upar se log gadiyan leke ke bhi aa jate hai.”

(“Issues faced are many, however, navigating through this crowd is a major one. Moreover, people entering with vehicles make it worse.”)

Though they are recognized as vending zones in India, there are no standardized guidelines for a Mandi leading to an unorganized arrangement of stalls, overcrowding and the possibility of getting lost. People also enter with vehicles, mostly two-wheelers causing danger of accidents. Vulnerable populations, especially the elderly, though wanting to visit a mandi on their own, are unable to do so owing to such hindrances.

“Mujhe toh aaj kal yeh sab uthane aur jhukne mein dikkat aati hai. Isiliye akele bazar aana mushkil ho gaya hai; yaha baithne ki jagah hoti toh accha hota.”

(“I nowadays face difficulty in lifting these bags and bending to check the vegetables, therefore I find it difficult to come shop alone. Had there been an arrangement to sit, it would have helped.”)

As one gets older, problems that start to become obstacles include the fear of falling or being pickpocketed, difficulty bending down to buy items, carrying multiple bags, and a lack of seating spaces. Uneven road surfaces, lack of signages and inadequate nighttime lighting exacerbate such concerns.

“Beta, hum toh yaha din bhar baithte hai toh roz marra ki takleefein toh hoti hi hai."

(“We have to be here the entire day and therefore face many daily life problems”)

Most Mandis lack the provision of public conveniences, which are a basic requirement not just for the elderly but for all, primarily the vendors who have to sit there all day. Amenities like drinking water and shaded resting spaces are also lacking.

“Yaha sabke sath ek rishta sa ban gaya hai. Sab dukandar dadi keh ke bulate hai, aur sabzi lene ke sath, logo se batein bhi ho jati hai.”

(“Everyone here has become a known face. All vendors address me with respect and along with shopping for vegetables, I also get converse with people.”)

With time a bond forms between the vendors and the elderly. The respectful treatment and the opportunity to see and talk to both known and unknown faces make the mandi a favorable place for frequent visits. So, if the public spaces, especially those of regular use are not designed to meet the needs of the elderly, they may effectively be trapped in their own homes. Going out even just for a short walk to the mandi can be comforting and a means of happiness for them.

All of these problems tend to get highlighted when looked at through the lens of old-age, however, these issues are faced by many others as well. Therefore, if addressed and resolved, through design interventions, Mandis can be made a lot more accessible and inclusive.

The Change:

Designing for a Mandi is a complex multi-layered process; while its dynamic character cannot be restrained or recreated, the intangible aspects can be protected and enhanced through design. There is always a pertaining risk of over-designing as there are multiple tangible and intangible factors associated with it. Nowadays, vegetables and other necessities are available in many built establishments like supermarkets and malls, with everything organized and labelled in aisles. It has all of the conveniences, but the social interaction and freedom that one experiences in a Mandi cannot be matched by highly-designed supermarkets. Therefore, while we plan to design interventions on a reproducible scale, we do not want them to be overly designed to the point where it takes away the genuine spirit of the Mandi. Furthermore, a Mandi cannot be abruptly set up anywhere, as it is a result of the choice made by people, both, vendors and customers, over the years to be at the location. To completely ignore them and set up new ones is a superfluous waste of resources. As a result, our interventions are designed to be easily implemented in existing Mandis. In doing so, we will preserve the ease and sense of belonging that the elders have established over the years while adding a new layer of comfort by design.

Our proposal aims to design an inclusive, enabling, and empowering environment, keeping in mind the needs of the elderly while making sure to not make them feel excluded from the rest. The interviews helped us navigate the complicated web of design problems and limitations with a little creativity and common sense; making us realize that the simplicity of the interventions will in turn ensure successful implementation.

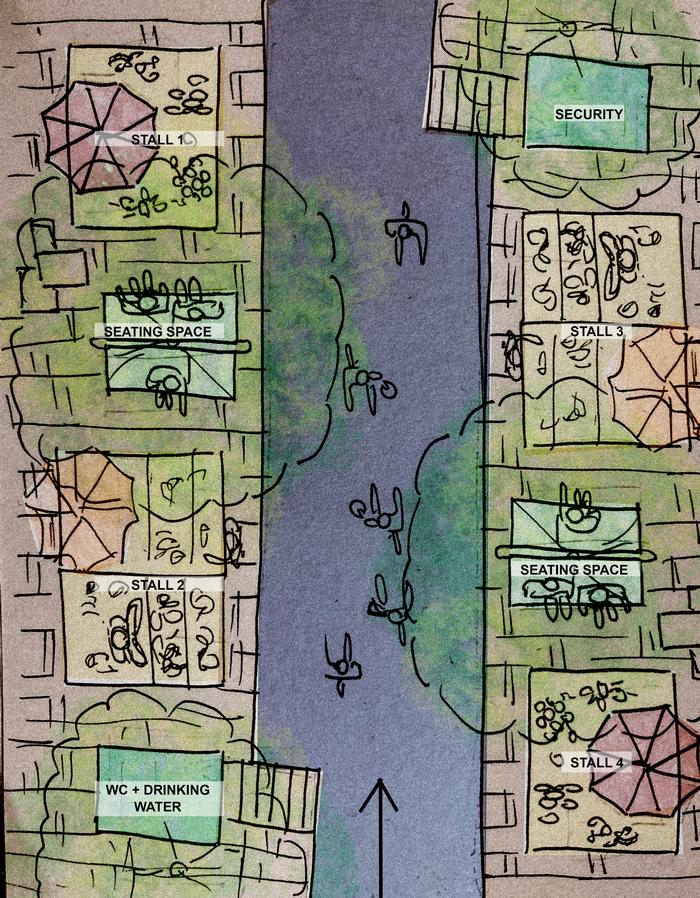

The biggest issue persisting in any Mandi is overcrowding and congestion. With stalls on both sides of a pathway, lanes can be divided. The division does not need to be restrictive but separate tactile flooring would create an idea of lanes for people to walk in a more defined manner and would improve the surface for walking. These lanes, preferably three, would be divided as such: one in the middle for walking continuously and two on the sides to stop and shop. Moreover, vehicles can be restricted completely or limited to the middle lane to reduce safety hazards. Along with these, different signages can help the elderly to navigate. In a Mandi there are usually multiple entries and exits with different amenities outside the area; the signages can depict them so the elderly as well as others can have easier and fast access to the facilities.

While designing an inclusive Mandi, the perspective of vendors is also equally important. The stalls can be redesigned on a raised platform with steps, to showcase the vegetables in a better way at a more approachable height for the customers. The stalls can be spaced out at intervals to accommodate public seating areas. With proper orientation, these areas will not only serve as a resting space but also a social space that gives an opportunity for the customers to pause and talk to vendors; this could be only achieved if the seating spaces are incorporated amidst the stalls and not on roads or faraway areas. Moreover, smaller stands can be designed to keep heavy bags. Such street furniture can accommodate lighting, dustbins, and green elements seamlessly within themselves. These will add to the liveliness of Mandi and enhance the experience for the vendors sitting there for the whole day. For an older person, public conveniences like drinking water, toilets, first aid and security are also equally important as is the physical and social landscape. Therefore, provisioning of such services in an accessible and well-maintained condition is also essential.

Our proposal is a humble approach to making the Mandis of India more inclusive urban open spaces. This can be implemented through the efforts of local NGOs working for the well-being of the elderly with the help of government grants. Also, cities wherein the Smart Cities Mission (an initiative by the Government of India to develop cities through smart solutions) is being implemented can incorporate Mandi redevelopment projects. Furthermore, architecture and design colleges can take up the designing aspect of such projects which can then be implemented through the ways mentioned previously.

A Mandi is not just a marketplace but a part of the cultural essence of India, an emotion that forms an intricate part of our lives. As an elderly, oftentimes it is difficult to find spaces that are designed to support their pace of life. While the rest of the world is changing, and the country is embracing new concepts of modernization, it is the Mandis and their welcoming nature that remind the elderly of their experiences that shaped them into who they are today. A Mandi belongs to everyone; hence we intend to transform the Sabzi (Vegetable) Mandi into a Sab-ki (Everyone's) Mandi.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |