[ID:4736] The Built Environment’s Response to Aging in Place in Metro AtlantaUnited States Introduction

By 2030, 1 in 5 people in America will be over 65, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2017 National Population Projections. Despite this growing aging population, many communities are ill-equipped for their senior citizens to successfully age in place.

Cities must create comprehensive plans that address the barriers to aging in place, including the lack of affordable housing, inaccessibility, and effective public connections. At the same time, the built environment must provide safety and prevent social isolation. Without efficient measures, adults will one day reach an age where their needs are no longer met by their built environment and face a familiar ultimatum: relocate or lose their independence.

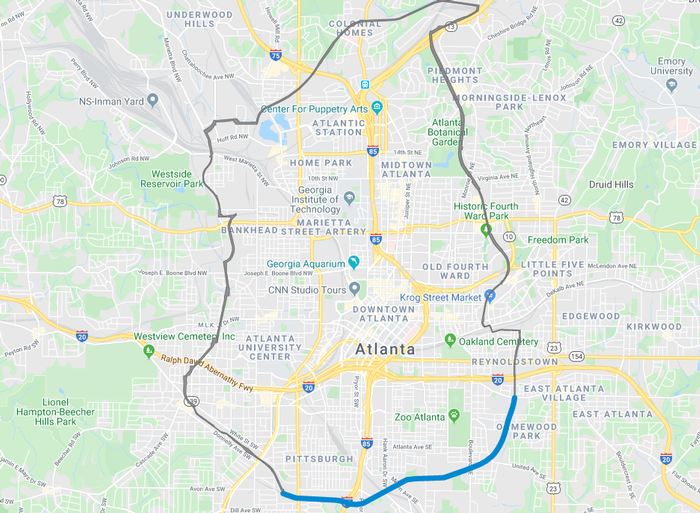

Atlanta has faced many of these problems, such as urban sprawl through white flight, which has introduced barriers to aging in place. Fortunately for Metro Atlanta, the Atlanta Regional Commission (ARC) has implemented Lifelong Community Initiatives to improve the built environment and encourage aging in place. These initiatives increase the quality of life for individuals through connectivity, diversity of housing options, transportation options, and walkability, as well as provide more access to retail, social and health services. Atlanta is also constructing a 22-mile multi-use trail around its perimeter to connect the city called the Beltline, which has encouraged aging in place through a macro-urban scale increased connectedness. The city also improved its senior citizens' quality of life at the micro-scale through internal neighborhood connections and affordable senior housing projects. Through these, as well as other initiatives, Metro Atlanta is uniquely promoting aging in place.

The Built Barriers and Their Beginnings

Senior citizens struggle to age in place because they have limited mobility, an increased risk of falls, and face obstacles to their everyday tasks due to memory concerns, social isolation, and other health risks. Environmental factors should serve to reduce these obstacles rather than intensify them. Unfortunately, the environment can compound these physiological barriers to aging in place by isolating individuals from resources and social interactions and preventing healthy, independent physical activity.

While these barriers are nationwide, the senior citizens in Metro Atlanta are particularly disadvantaged because the region predominantly comprises traditional suburban communities, discouraging walkability, development, and accessibility to services and resources close to home. More problematically, Metro Atlanta is comprised of diverse neighborhoods that lack effective inner-city connections despite having a metro system, MARTA, and the growing Beltline.

In the US, Savannah, Georgia, was the first planned city, and it was successful due to its intent to connect public squares and parks through a series of wide streets laid out on a grid. It served as a model layout. However, since this country was formed, that model has adapted to accommodate the new-found ideals of the American Dream. In the 1950s, the appeal of more affordable housing, post-war affluence, the rise of automobiles, and racial tensions led to a retreat to suburbia. This movement intensified during the 1960s as Atlanta, the "city too busy to hate," experienced white flight - a migration of whites out of the urban areas to suburbia for fear of places increasingly becoming more racially diverse. This, in turn, led to a drastic disconnect between Metro Atlanta neighborhoods. With a massive migration to the suburbs, the city was abandoned, and with it went the money necessary to upkeep and growth.

During the 1960s, in Atlanta's Historic West End neighborhood, the city tried to stop white flight and even introduced a new MARTA stop in the neighborhood to no avail. The idea intended to raise the location's appeal through increased access to the rest of Atlanta. Instead white flight from the area grew because a public transportation stop would encourage more integration.

Even with the rise of the suburban population, Atlanta tried to keep its city connected and began a movement to extend the MARTA outside the perimeter to Metro Atlanta. However, communities like Cobb County immediately voted against the public transportation connections. These stances from the 60s and 70s have left lasting impacts today, and Cobb county is still vocalizing its destain by consistently fighting against the expansion of the MARTA.

The bottom line is that much of this city's sprawl began in the 1960s due to racial tensions and a refusal to accept desegregation. This has created an underlying lasting system that benefits the able-bodied, young, privileged upper class and pays little to those marginalized: the poor, the elderly, and minority groups. Those who are part of one group, let alone all three are likely to feel the negative impacts more significantly than the rest.

Today, the Historic West End Neighborhood is a predominantly African American community. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, the community fell victim to mortgage fraud and struggled during the recession; many homes foreclosed. When the Beltline's West End trail opened in 2008, the housing values drastically increased. Since the community was amidst economic downfall, many long-term residents could no longer afford to live in the community they had called home. The timing of development was cruel because the senior citizens who had lived there their whole life were forced to abandon their homes.

Overall, due to the historical events, the neighborhoods in Metro Atlanta are sprawled and disconnected and need more affordable housing. These remain the most significant barriers for its senior citizens to age in place in Atlanta.

The Beltline’s Impact and the Race to Create Affordable Housing

Many acknowledge the divide within the city of Atlanta and have made efforts to mend it, such as Ryan Gravel, a Georgia Tech student in the 90s. In his thesis, Gravel proposed a transit greenway connecting over 45 neighborhoods to the city's schools, shopping districts, cultural destinations, and public parks to address the city's sprawl. Its primary intent was to reinforce Atlanta's dominant center and reinvent public space by creating an easy connection between the home and destination for various socioeconomic groups. This would combat Atlanta's urban sprawl and suburban expansion, which disconnected residential areas from services. While not the project's initial intention, the Beltline's design has been instrumental in addressing aging in place.

His thesis also proposed a light rail running alongside the walkway, which is to be built by 2050. This light-rail system could connect aging adult communities to healthcare facilities without relying on someone else to drive them. Even without a light-rail system, it provides a safe, walkable connection to different services, promoting physical activity. Overall, the Beltline creates a convenient connection with vital services that encourages independence.

One of the unintended consequences of the Beltline is the rising cost of housing along the Beltline. Gravel's original thesis promoted affordable housing with the Beltline's construction. However, these elements failed to be included when the plan became actualized. This issue is particularly concerning for aging adults living on a fixed income because when the Beltline's construction creeps into their neighborhood, they are offered "compensation” to move. They have no choice but to accept the compensation if they are not financially privileged to remain in the area.

To rectify this depleting access to the housing along the Beltline, there is a race to build affordable housing. The Reynoldstown Senior Residences is an affordable senior housing project just one block from the future Beltline Eastside Trail extension. The project was partly funded by a $1.5 million Beltline Affordable Housing Trust Fund grant through a partnership between Mercy Housing, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the City of Atlanta, Invest Atlanta, and the Georgia Department of Community Affairs. Once the Beltline is complete, this senior residence will create multigenerational connections to the rest of the city and provide active opportunities for its members as they can bike, walk, and immerse in their community.

For everyone to effectively age in place, there needs to be a consideration of how various socioeconomic groups can benefit. To only allow the white upper class to utilize the newly built infrastructure would be directly antithetical to universal design - the design of buildings, products, or environments to make them accessible to people, regardless of age, disability, or other factors.

How Metro Atlanta is Actively Addressing Aging in Place

While the Beltline effectively addresses barriers for senior citizens at a macro scale, it misses out on the micro issues within each neighborhood. Fortunately, Metro Atlanta has not turned a blind eye to these issues as it has deliberate programs to address suburbia’s lack of internal systems and the inner city neighborhoods' isolation. Architects, urban planners, public policy experts, medical professionals, and others are designing solutions through an interdisciplinary approach.

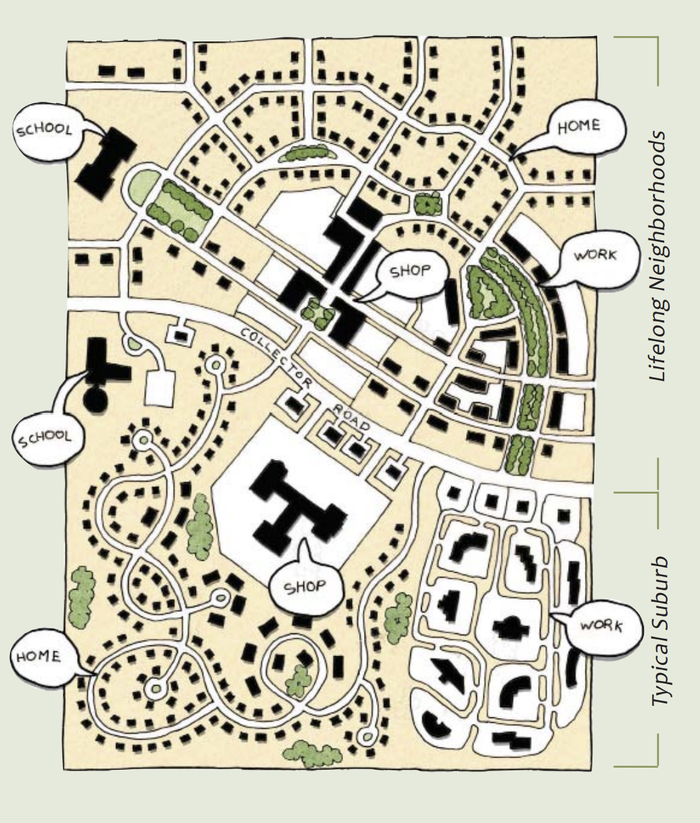

The Atlanta Regional Commission (ARC) has implemented Lifelong Community Initiatives to improve the built environment and encourage aging in place. The initiatives follow a three-plan framework to provide affordable housing and transportation options, promote healthy lifestyles, and expand access to services. Just like the Beltline proposal, lifelong planning emphasizes the quality of public spaces. The intent is for these public spaces to support mobility and interactions between different generations. These initiatives are applicable in urban and suburban environments, making them perfect for Metro Atlanta as they can retrofit the suburban communities and improve the quality of life for all ages while also strengthening urban areas. Furthermore, the suburbs do not have to disappear but rather evolve to create a lasting positive environment for future generations.

Today, Mableton, Georgia, serves as a model case study for implementing these initiatives. Before the community began developing into Lifelong Communities, it was a traditional suburban neighborhood. Mableton even won the 2011 Commitment Award from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's Building Healthy Communities for Active Aging program for its effective engagement with its community and application of new urbanism, leading to environmental and health benefits.

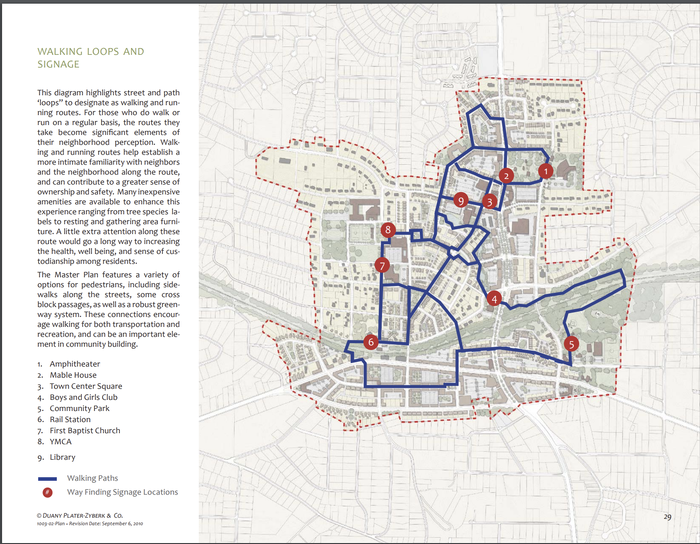

Mableton's renovation began with a charette open to all its citizens to design a new master plan for the community. The new plan emphasizes four separate nodes: the Old Town Center, the Barnes Site, the John Mable site, and Mableton Elementary School. These nodes are connected through cohesive pedestrian sheds and redevelopment of the retail center. It also redevelops the elementary school as a campus to serve the entire community through education and wellness programming. Many of these wellness programs target the community's aging adults.

This plan is flexible to the city's growth, promotes walkability, and creates a stronger knitted community. At the same time, it implements internal bus routes to connect its citizens to different services. These internal transit stops would help its senior citizens independently go about their daily lives. The master plan also will further connect the community through greenways, public civic space, small plazas, and pocket parks, with walking loops and signage to help with wayfinding. These wayfinding strategies are vital for the average senior citizen to encourage independent navigation.

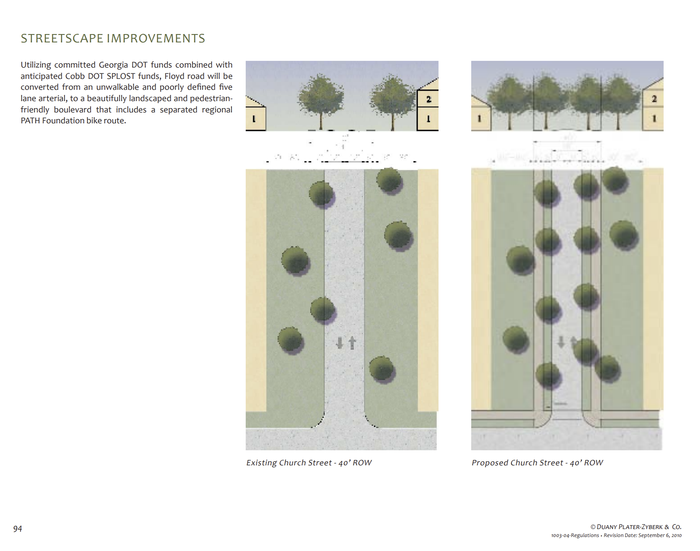

The master plan also includes zoning Smart Codes which encourage mixed-use development in addition to retail development, sites for civic buildings, public health services, and open space, all within walking distance. It also includes the redevelopment of existing large lot single-family properties to provide greater density and create emphasis along a main street. Additionally, the plan proposes renovating existing streets to improve accessibility for pedestrians and bikes.

Overall, the effectiveness of ARC in combating suburban barriers to aging in place is seen in Mableton. Mableton’s initiatives implement a universal design and new urbanism ideals, which promote environmentally friendly habits through walkable neighborhoods with an extensive range of housing and job opportunities.

These initiatives are seen even within the inner city of Atlanta. The Inman Park neighborhood has begun reviving its master plan with Lifelong Community Initiatives. This includes installing walking and bike paths, designing a new park, including more trees, and developing smaller homes within walking distance of downtown.

With these neighborhoods revamped to reconnect internally and externally, Metro Atlanta has the promise to become the ideal place for the aging adult. However, these initiatives go beyond just the aging adult. The key takeaway from the Lifelong Community Initiatives is that everyone prospers by utilizing a universal design. What improves the quality of life for the aging population also benefits the younger generations: its impact goes across all stages of life.

Additional Atlanta Programs for the Individual Home

Furthermore, volunteer groups, such as Neighbor in Need, strive to help its senior citizens, particularly those without the financial means to age in place. The program repairs over 50 houses annually in over five Atlanta neighborhoods. Not only do they repair houses, but they also improve accessibility within homes. For instance, they have created ramps to replace steep stair entrances and installed grab bars within bathrooms to decrease the risk of falls. Most importantly, the group pairs low-income seniors with lawyers and estate planners to help them preserve economic stability and remain in their homes, mainly when offered "compensation" as the Beltline develops.

The Cognitive Empowerment Program within the Druid Hills of Metro Atlanta utilizes evidence-based design to improve homes and communities to serve senior citizens suffering from Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). Those with MCI are in the stage between a severe decline in memory and thinking which can potentially lead to Dementia. This program is led by both Emory and the Georgia Institute of Technology and brings in various researchers who codesign products to encourage aging in place for those with MCI. The program is currently designing a Home Design Tool kit with guidelines and minimal changes to make in the home to encourage aging in place. This includes various lighting conditions, noise concerns, organization, and house layouts. The researchers plan to publish these guidelines, so individuals retain their autonomy.

Conclusion

While Atlanta has several plans to assist the aging adult, the essential fact remains that the city must execute these plans with the utmost consideration for the population they seek to serve. Otherwise, like the Beltline's lack of affordable housing, they will need more to accomplish their objectives. As for minimal changes which operate on a much smaller, local scale, such as improvements to housing, these improvements may be comparatively subtle, but they can be realized much sooner and serve as an indication of Atlanta's incremental movement towards serving the aging adult. Both in the short-term and long-term, Atlanta has excellent growth potential. Once these developing plans come to fruition, the city may be a comfortable home for seniors and younger residents.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |