[ID:4591] Quilting The Crevices: Restructuring Lives Through ArchitectureIndia March 24, 2020

"I walked through the day and I walked through the night. What option did I have? I had little money and almost no food," said Mr. Meena with a raspy and strained voice.[1]

He has been toiling in poverty along with his family of six, all of whom he can barely manage to feed; his children susceptible to vulnerable diseases. And now, with no money to pay for the rent, they have ended up on the streets.

Lamentably, they were not the only ones. Visuals of thousands of workers wearing gamchas, carrying heavy backpacks, boarding tractors, and jostling to find a spot above multi-colored buses became defining images in India for days to come. Many had no choice but to walk. Some traveled a few hundred kilometers, while others a thousand to reach their native places. Some had infants and expectant spouses, and the lives they had built for themselves were crammed into their threadbare bags.

Many never made it.

A slew of obstacles, including potential starvation and despair, dread of COVID-19 and social prejudice, highlighted their fragility. Overnight, the city they had worked to construct and manage seemed to turn against them. The staggering exodus was reminiscent of the flight of refugees after 1947's tragic division of India. Around 15 million bedraggled refugees were then displaced cross-border. Such was the situation with migrant laborers as India declared the world's largest lockdown to curb the spread of COVID -19, urging its citizens to stay at home.

How does one stay at home when there is no home?

Unfortunately, not every stratum of society lives in the settings that they may proudly call 'home.' The heterogeneity in Indian society is starkly expressed when a door of a rich man's house costs as much as an entire house that someone from the lower strata could afford.[2]

Classifying the fight against Coronavirus as a "war" has justified far-reaching measures. The repercussions of the shutdown on different sections have underlined the stratification of Indian society. While most middle-class families supported the government's measures, the interstate migrant laborers were left overlooked.

Life in a Crevice

An analogous life structure could be observed in the colony of Majnu ka Tila, located at the northern fringe of Delhi by the bank of river Yamuna.

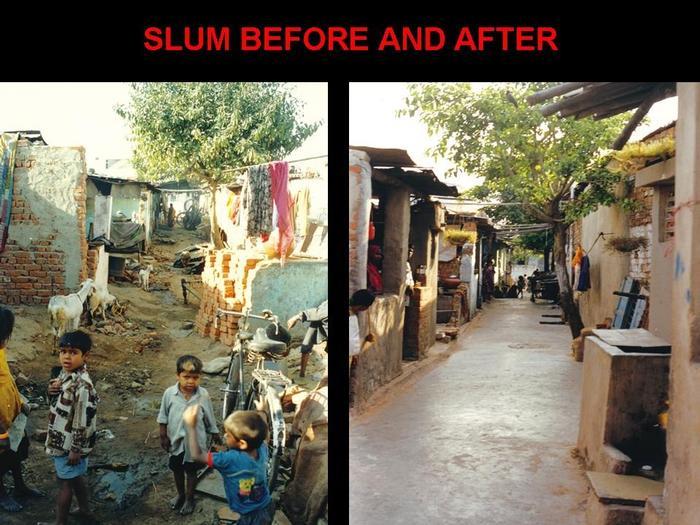

Ethnically and religiously diverse, Delhi has struggled for years with overpopulation, corruption, crime and poverty. A majority of the city's functioning is supported by migrant laborers, who, under the glittering decadence of the city's powerful elite, are shoved to the outskirts, both in the space and imagination of town planners. A stunted urban infrastructure characterizes the Tila - uneven and filthy paths, blocked sewage lines, crumbling sheds of tarpaulin and a myriad of socio-economic issues. Sewage pours outside through open pipes before settling in the streets where children play barefoot.

One could compare their praxis to living in cracks and crevices of an old building, where the sun shines, but the rays barely reach the compact zigzag spaces. From its minute door, the world’s view illustrates a bleak path of despair and dejection. Still one can muster hope in some to get out of this tunnel one day.

Seeking shelter, security and a sense of belonging are the primal instincts of any living creature and humans are no exception. Yet too often, the architecture of basic shelter is left to the poor themselves, who build or adapt to ad-hoc structures, or else to bureaucrats whose designs do not address their needs. Tila's squatter colonies are often viewed as unsightly, illegal encroachments on government land instead of desperate last-ditch survival attempts by destitute people defeated by a fatally crooked system.

Past Berkeley Prize winners have formulated architectural solutions inducing equality and cultural integrity while exploring sustainable design solutions. The BP’22 question presents new avenues for designers to rethink the idea of a house. We aim to touch upon an area that has not been amply explored - making observations that are personal to the users. An attempt has been made to have community participation and impart a sense of self-ownership.

Architect of Their Own Lives

The first step in our endeavor is to critically understand the users, their sense of space, histories, cultures and traditions, and incorporate them later into the built environment. In order to accomplish this, the design activity must take into account the mechanisms and beliefs that shape their daily living. Henceforth, the process requires us to expand our involvement beyond the drawing board, seeking to become a part of the procedure of formulating the program, the proactive and ideological foundation of the space we will assist generate.

The sequence of approach that we willfully second is to get an insight into their lives through dialogue with the children. They will be upfront and honest in discussing their struggles and aspirations. Following the bottom-up series, the next step will be to engage the adults, who by this time would be conscious of our project and probably would have built trust in the process.

To better understand the community, we plan to constitute a questionnaire that will include the basic demographic questions regarding age, sex, cultural ethnicity, family size, skills, daily routine and needs, thus creating a database for future analysis. Our effort will be to perform a simple random sampling to approach ethnographic research, henceforth collecting opinions of all forms while simultaneously using the methodology of participant observation.

Recasting the "vision plan" as a storytelling exercise shall get all ages and backgrounds invested in the planning/devising processes. We endeavor to engage them in fun and productive activities where they construct a model of their dream house, using primary materials such as matchsticks, newspapers and stones. Another way would be to bring a series of visual collections in the form of pictures that could be put together into a mood board with the community's help.

While we can establish a framework of the processes, all of this can be brought to life with help from experienced professionals. To further the agenda, we shall build a "Community Engagement Foundation" (CEF), a working group with representatives from the community, student volunteers, government bodies and NGOs in this domain.

To begin with, we shall engage Nivasa, an architectural NGO. Initiated by a group of dedicated individuals, Nivasa is a design and build a venture that seeks to provide professional designing input - employing a people-centered approach. They have developed a housing toolkit with region-appropriate housing solutions and cost-effectiveness by involving the house owners in decision-making and construction processes.

"Instilling knowledge in him, exciting his intentions and getting him to practice building his home, make the owner the advocate of change in his life," says Akhila Ramesh, founder, Nivasa

Having the ease of readily discussing their views with the team would allow them to voice their opinions and worries. The team will thus contribute to making a more robust community at multiple levels and emerge as a nucleus for welfare, making people feel substantial, unconstrained and secure, thus boosting their self-confidence.

Furthermore, we shall identify the wasted or underutilized spaces in the area. A desolate land transformed into a dumping ground on the outskirts of Tila might be a viable location. Since the neighborhood inhabits a sizable percentage of the population, its proximity will prevent them from being relocated. Taking out the debris and other waste would free up new space while providing a hygienic environment.

A Collated Effort

The next step will be to begin the designing process. An effective starting point to address this is through a design competition. We propose to conduct, 'Community Impact Architectural Design Competition,’ which would rest its premise on the question: "How can we, as citizens, innovate the status quo into a more sustainable paradigm?"

The purpose would be to spring an incubation box for a design that attends to the requirements, raises awareness, sparks creative ideas and buzz. Students of architecture and similar fields could be invited to participate in the hands-on opportunity. While the objective is to develop a formal approach, it is not intended to limit imagination; it will be up to the students' ingenuity to define. It would become a two-pronged approach, sanctioning individuals to emerge with solutions that disentangle the problems and address the critical issues within the process of generating ideas. It will be more than a design competition; it will stimulate social activity in itself.

As a byproduct of this collaborative effort, we would develop and build prototypes of various characters by proposing ideas via physical models, sketches, and stick figures, thus synthesizing various essential aspects of community living. The endeavor would progress into a full-fledged investigation of the region's cultural environment and history. For instance, traditional Indian architectural features such as the raised entry, multipurpose spaces, the perimeter wall around the house and small spaces dedicated for worship, will all need to be combined with a modern understanding of human nature and successful urban design.

Neighborhoods could be considered as a critical aspect that reflect how local communities live and cultivate bonds. They tend to have a 'cultural weight,' building connections between different households. A shared outdoor space can be used for gatherings and day-to-day grouped activities without jeopardizing fundamental privacy concerns. Incorporating an 'Aangan' (Courtyard) might further help to nurture the community nexus.

Serving as a bio-centric architectural paradigm, we plan to utilize local materials and low-energy processes. For instance, limiting the material palette by using materials known to the locals and are simple to deal with could be an excellent strategy. The existing tin shelters could be replaced with bamboo frames, double walls and air cavities for better insulation to extreme winter, heat, and monsoon climates. Consequently, with the assistance of Nivasa, we would teach and train the locals in fundamental building procedures and materials. This would enable the structures to last for an extended period with minimum modifications.

As a result, we shall evaluate the various design proposals received through the competition within our working group. We plan to understand what kind of design choices our homeowners need to feel in control of their space. If our blueprints contain segments that do not cater to their needs? Do we need to incorporate anything else that could highlight their individuality? Are we moving in the right direction?

Sewing The Gaps

While much of the work on the design part can be done, parallelly, we would require to approach the establishments to help us with funding. Putting the final pieces together, CEF plans to use a two-forked technique for generating funds. The most viable approach would be to show our investors/donators what we are willing to bring to the table as a project alongside our contribution to the sum raised through various fundraising activities and competitions. With such a proposal, collaboration with an actively working NGO could assist us through their connections in the municipality, individual and corporate donors, and international organizations to fund our efforts. The local government/council could also be compelled to contribute funds through Prime Minister Awaas Yojana (PMAY), a central government housing scheme to help the economically weaker section. To create a sense of ownership, we shall seek users' involvement as 'Kar Sevaks' (voluntary laborers) and contribution as a minimum financial component to take advantage of the currency they possess: social currency.

Once through with the construction, we emphasize the need for holistic development, self-reliance and skill generation, creating a place that is eventually flexible to people. Thus we plan to engage with the Disha Foundation.

Initiated by Anjali Borhade, Disha Foundation has been working in health, livelihood, and legal assistance and has launched various direct interventions emphasizing and enabling people to utilize available resources. Disha takes extraordinary efforts to actively engage local, state, and national government officials to bring about changes that promote equitable development and impart skills. This, in turn, will provide us with an opportunity to connect with governmental and non-profit organizations that have traditionally supported public health and self-sufficiency. Because of that connection, the practice of public-interest architecture would have substantial research behind it, as well as a more diverse set of disciplines.

A New Chapter

The building process symbolizes the challenge that awaits the citizens of the country. It sets a noble precedent by affirming the significance of first recognizing and alleviating the misery of the lower layer of society in order for a country to progress.

The rich of Delhi live their sheltered lives, detached from the suffering of ordinary people, seen only through the windows of their air-conditioned cars. Developing this new housing project could begin the process of erasing these borders. It would be critical to establish a character that reflects the identities of the people and the key lies in giving them control of the new development while simultaneously making them self-sufficient through skill-building workshops. Housing is more than just an architectural problem; it encompasses a wide range of elements. Architecture must work as a facilitator for holistic development, bringing together numerous other sectors for community development. The dwellings must function as genuine homes, allowing individuals to paint their way of life onto the raw canvas of the architectural form. One would commit a mortal error by imposing conditions and ideas that do not sync with their desires or comfort levels. These dwellings must shape people's lives by establishing an economic and social balance in their new surroundings.

The notion of 'community' is no less than that of life. It is an autopoietic machine - self-emergent and self-organizing.[3]

The project would become the core of the city's collective dreams and aspirations, and develop a contemporary, flexible and progressive identity deeply anchored in the region's cultural past. The housing project would be one of the few in the chain of initiatives around the city serving as an example for economically feasible and culturally relevant works of architecture. It would usher in a new period of rediscovery and enlightenment that is not limited to architecture alone but covers all areas of modern urban life.

"A society that still has a goal still has an icon is a society supported by the concept of progress." – Kisho Kurokawa.

It is evident that very little change can be brought about without first establishing a secure and just society with a functioning democratic system, but a project like this would transform into a sustainable model suited for community-centric practice that is affordable, adaptable and accepted.

Works Cited

[1] Biswas, S. (2020), Coronavirus: India's pandemic lockdown turns into a human tragedy

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-52086274

[2] (2021), Timmaiyyanadoddi – A village intervention

https://gramnivasa.wordpress.com/category/world/

[3] Paul-Chakraborty (2019), Nests for a Phoenix: Building Life After Death

Works Consulted

Ramhotar, A. (2006), Our Children, Our City: Our future

http://berkeleyprize.org/competition/essay/2006/winning-essays/ashween-ramhotar

Yeap, P. (2008), Good Vintage - Sustainable Architecture for an Ageing Society

http://www.berkeleyprize.org/competition/essay/2008/winning-essays/yeap-essay

http://www.dishafoundation.ngo/projects/policy-advocacy

https://nivasa-ngo.org/projects

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |