[ID:4519] The Paved Night Sky: Finding Sustainability and Inclusivity in the Age of GentrificationDenmark In 2021, Copenhagen once again rose to top the Liveable Cities Index. The city strikes as a break from other modern cities. In summer, the harbour of the city centre at Islands Brygge is lined with hyper teenagers and the sound of tanned, sculpted bodies hitting water. The sun sliding off all the movement. In winter, Viking souls venture into the icy water at Nordhavn before grabbing a coffee before work to sit and look out over the Baltic Sea. And no matter the season, a steady stream of cyclists sweeps through the city. Notably, Denmark is a worldwide leader in sustainable development, boasting a welfare state that strongly promotes equal opportunities i.a. a strong universal health care system, low tuition rates, low crime rate, generous unemployment benefits as well as clean and efficient energy production.

From this, it may seem unexpected that Copenhagen, presented as the textbook example of sustainable cities, is being featured in this context of the Berkeley prize. Whilst its less glossed-over face does not exactly correspond to the Denmark of Marcellus’ ‘something is rotten in the state of Denmark’, the city however cannot be represented through the utopia the media has painted it as. The capital has seen a vast change of landscape in the past decades and generally one still cannot escape the sustained sound of construction. These changes are greatly attributed to urban renewal or revitalisation which are mostly in the form of gentrification. The process has given rise to homes with sleek and minimalistic Scandinavian interiors. Beautiful but homogenous: the interiors that all look alike, bearing the same white walls, wooden floors and exact same kitchen units.

Homogenous- this reflects Denmark’s society to a degree. The tight-knit group of only 5.6 million Danes, draws a circle that leaves vulnerable groups subjected to discrimination and less able to participate in society. This includes growing rates of poverty, which have affected vulnerable groups such as single mothers, the elderly as well as families with needs. A factor of their plight is the cost of housing, which has been increasing over the past years due to high rates of gentrification, with apartments mainly being privately owned and rented out at high prices. This situation leaves space to improve progress in inclusive and sustainable urbanisation.

Sustainable urbanisation has been at the very core of Stejlepladsen. Since the 80s, it has been the seedbed for a diverse set of inhabitants: artists, architects, fishermen and many others could easily find a place to call their own due to the accessible price of land. The different colours and materials are a kaleidoscope through which the owners can be seen. Self-built culture is strong here, and so is the sense of community. As Nanna, a local artist, puts it: “Everyone is welcome, even the strange.”

As one steps inside, one notices that the borders of the houses are more fluid, that weeds sacredly dilate and that each house boasts an entrepreneur, with a small second-hand stand flourishing without supervision. Trust is imminent and space exists between an organic understanding of what is shared and private. Gardening is a collective experience, as well as nature. Stejlepladsen boasts nature that has been allowed to grow as it wishes, which is a rarity in the metropolitan city. As the residents put it: nature gives them ‘peace’ and a feeling of being in a ‘magical’ space. For the inhabitants, it is as essential as their homes.

For a long time, this village has been able to escape from the all-encompassing sound of the concrete construction, as the harbour town was hidden away from the city. Nevertheless, Copenhagen is expanding and the time for Stejlepladsen to also grow came in March 2019. But as the inhabitants may say: it was just not in the right direction. Formerly protected natural areas were reclassified and stripped of their protected status. Now, more than 550 luxury apartments are being established on this land. Construction is being executed by By&Havn, a public-private partnership that was installed in the 1990s by a social-democratic mayorship when Copenhagen was near bankruptcy. The firm got the city out of bankruptcy by selling public land to the highest bidder, a practice that is still sustained today. Now, Stejlepladsen’s gentrification came in connection with the plans to expand the metro in the region and the municipality’s need to cover this budget. As one may already imagine, it did not go over well with the out-spoken inhabitants; all the newspapers became involved, meetings were quickly set up and a local organisation, Sydhavnens Folkemøde, was established for the sole purpose of ending this construction. Katrine West Kristensen, a resident and member of the local group for shared residence, summed up people’s anxiety about the construction’s change of Stejlepladsen’s culture: “There is space [at Stejlepladsen], not only physical but also spiritual. There is space for various kinds of dreams too. With the new construction, this will surely be affected.”

Going back in time, it can be valuable to analyse the process of how the value of space is calculated in a cultural setting. If one would ask the municipality, it would be by giving points after a 15-minute inspection of the entire space. Rikke Stenbro, an art historian and conservation adviser, worked precisely in this field before she quit to start her own firm that follows a different system. In her eyes, the nature at Stejlepladsen went through the same process. Its worth was calculated and limited to a monetary plane. Moreover, what pained the residents the most over the construction was the feeling of not being heard. They found themselves, their questions and concerns to be ignored at the meetings between them and the architects. The miscommunication between the inhabitants and the architects resulted in a sour and cold relationship, which no abundance of meetings could repair. Good design will never manifest if it is not created for the people and with the people. As Giancarlo De Carlo puts it: “Architecture is too important to be left to architects.”

"They took away our stars'', says Nanna. Gentrification is seeping into Stejlepladsen and despite new architecture being sleek and sustainable, the stars will be poured over with thick concrete; its darkness not as permeable as that of the night.

When we look up at the night sky’s stars, we often feel a sense of loneliness and longing. The stars are sole and independent entities. Yet they are not so alone- they exert forces on each other. Intangible and invisible as they may be, humans have through the ages drawn constellations, tracing these forces. These permeate our stories and mythology; from Cassiopeia hanging upside down to the cowherd and weaver girl reuniting into each other’s arms on the night of Qixi Festival.

Just as humans have drawn them on the primal canvas, they also draw them below on Earth between buildings. These lines are drawn of architecture and community through direct and tangible depictions such as roads. However, they are stronger in their intangible form of human interactions and social ties such as the community in Stejlepladsen. Together, a constellation will shine like the myth it tells, weaving the very constitution of our communities. And so, through the fostering of a strong community the night sky may become clearer again-

In light of segregation and marginalisation, the fostering of community must be strongly pressed. Hence, the groups we focus on are the elderly as well as families with monetary needs. These groups dovetail with the diverse profile of Stejlepladsen, where the inhabitants can more easily find a welcoming place through a community that embraces differences. To make regentrification sustainable and integrated, we will expand the area by constructing on the former party hall area that is adjacent to the current community and has now been cleared.

The drawing of the constellation already starts prior to the building process where, in order to further understand the users and to ensure the users are actively involved in the design and construction, weekly meetings that generate reports will be held to facilitate dialogue before and after the beginning of the construction. This is a point that has also been stressed in interviews and the former hearings between the Copenhagen municipality and the residents. The meetings will be expanded into community-building opportunities through events that are already part of the Stejlepladsen’s culture, such as joint dinners and a gardening club.

Furthermore, the community-building events will be expanded upon in the form of open invitations to participate in makerspaces: collaborative workstations where the people are supplied with the area and materials needed to create together. Here one could grow potatoes and cabbages or make colourful tiles to decorate the former and future buildings. A place for growing nature and repairing the old. With this, we would like to emphasise the importance of understanding what it means to expand and nurture the culture of any place that is set to grow.

As builders of space, we also need to know how to talk to the future and past inhabitants and how to analyse this information. This is the basics of anthropology and ethnography. After studying Stejlepladsen, we found three core aspects that we would like to focus on for the interviews: landscape/nature, community/values and materials. These three themes will tie into our main goal of fostering a community between the new and old inhabitants. Nature was chosen as it is sacred for the past residents. Therefore, sustainable materials and processes that focus on nature are emphasised.

These three themes will manifest themselves in the first more general stages of the interview (see proposal):

1. What is the foundation of your community?

2. What role does nature play in your house’s surroundings?

3. What makes you feel isolated from your community?

These broader questions set the foundation for the next stages of the interviews, where we can narrow down our focus to fit the narrative of Stejlepladsen. Through our consultation with Anthropologist and Professor of Space and Design at The Royal Danish Academy of Arts, Kirsten Marie Raahauge, it was possible for us to expand on our social science approach to this project. We understood that the questions had to also be focused on the everyday and that there are several ways to understand the users. From this conversation one of our conclusions was that participant observation must be done more interactively. Therefore, our questions focus on how the user interacts with a smaller version of a plain room; where they prefer to sit, how they prefer the light to be. By having the participant draw the places they cherish in Copenhagen and Stejlepladsen, we would also be able to visualise their answers.

The interview is an intricate collaboration that creates a display of the other’s mind: illuminating what is usually hidden to architects. When we ask about the relationship between the interviewee and nature, what we really want to know about are the ‘small pleasures of life’, a timeless concept coined by the architects Alison and Peter Smithson in 1993. With this in mind, we set out to create our questions about the everyday pleasures with the three themes as a healthy limitation:

Community/Values

1. How does your ordinary day go?

2. How would you like to learn from the new inhabitants?

3. What things would you like to do with them?

4. What are the values of Stejlepladsen that you cherish?

5. How do you throw your signature parties?

Landscape/Nature

6. Do you like to look outside the window?

a. What do you like to see there?

7. What trees or flowers do you prefer?

Materials

8. Would you like to live in a self-built place?

9. What material do you prefer in a building?

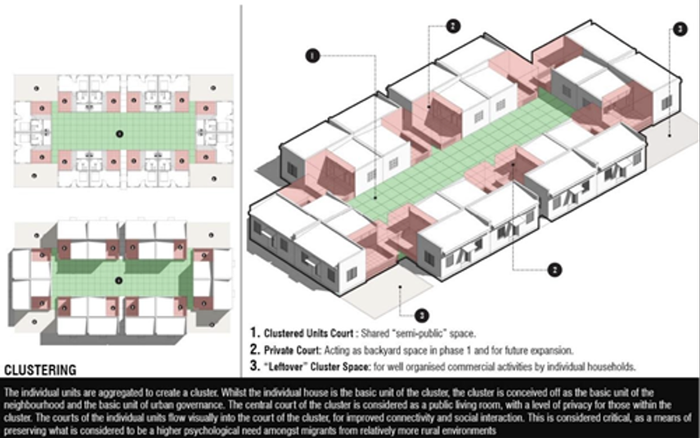

The construction process will also be taking time, so as to assure deep understanding of the needs of the users and have interviews focus on potential changes that could be made to the already built materials in its earlier stages. The idea of clustering the housing will be accentuated, as with each house facing a common point, community can flourish. Several clusters will exist: one for the people who prefer a more peaceful environment and one for the ones that prefer the festive atmosphere. The expandable housing will accommodate for changing family sizes, as housing should reflect the ever-changing progression of life.

The municipality would contribute with the land as it is owned by them and as a chance to integrate it into their affordable housing initiative. However, the funding will be covered by targeted funds. This includes the Velux Fund for the elderly, RealDania for sustainable buildings and finally A.P. Møller Fonden for families with children with special needs. Our focus on these funds is due to the fact that they go beyond solely monetary aid but also focus on expertise. Through this a truly community project will be underway.

Stejlepladsen should remain distinct in its culture however it can serve as an example of a more integrated and involved urbanisation for the rest of Copenhagen, which will see many areas affected by constant construction. This project can aid the city in no longer making the mistakes they for instance made during the gentrification of Vesterbro. There the municipality’s apparent aim was to include the inhabitants, who were mainly members of marginalised and exposed social groups, in the urban renewal process to prevent their dislocation. Despite this, due to a lack of concrete policies and consistent desire, the population was greatly pushed into Sydhavn, of which a large area also saw a similar trend in gentrification. To hinder an endless spin around a non-inclusive cycle of gentrification, Copenhagen can look towards the process of Stejlepladsen as an example, especially its more concrete and local resident-focused implementations, including smaller initiatives such as garden clubs.

In the end, the constellations we have drawn are both tangible and intangible: we have the roads and the planning in architecture that physically links houses and then we have the intangible in the sense of fostering links between residents, a community. Both are that whole we have created. And in order to understand it, one must listen to the constellation’s tale. This is what architects must do. We must draw on the culture and values of the residents, both past and future. The architect must respect the integration of the social sciences, biology and philosophy into the world of design until they fuse to strengthen our lines of the night sky and bring the constellation to shine in our night sky again.

When taking the plane from Kastrup airport at night, cities look like islands floating and pulsing amidst the darkness that falls everywhere else as though the world is submerged in a primal ocean. At those points, they bring to life the human drawn constellations of the stars above in a warmer and more kinetic light. And we should look down and keep an eye on Stejlepladsen. A new constellation may be spinning, one that will have a unique story to tell.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |