[ID:4488] Meeting the People's Needs Through ResearchNigeria In the western region of Africa, a country like Nigeria, which is made up of diverse groups and settlements, each with their unique ethnicity and culture, one cannot overlook the challenges within these communities. Inadequate housing, epidemics, insecurity and pollution are among the concerns that people living within these boundaries face. Over the years, the Berkeley essay competition, highlighting the role architecture plays in fostering societal transformation, has served as a platform for talented authors from across the world to bring neglected communities of this sort to the limelight.

Korukoru, a small town dominated by the Yoruba’s in Oyo state, Akinyele local government area is one of those communities. The ancient Nigerian community, surrounded by forests, is a neighbor to Merin, a town in Akinyele local government area. Its center, Meta, is a settlement of close-knit individuals whose clustered dwellings have facilitated their interaction with one another over the years. They value the act of working together and moving in groups all the time. They celebrate festivals together and when it comes to making decisions about their surroundings, these people hold meetings to discuss their every step.

Meta, at the heart of Korukoru, is a haven for the poor and disenfranchised. It is a home for elderly farmers toiling to feed their families, a home for mothers with babies, hawking their wares on large trays in market places to make ends meet and a home for youths who scavenge from waste, delivering scraps to usage corporations in exchange for small amounts of money; these are their sources of income. These individuals are at a deficit when it comes to having access to basic human needs. Education, which is a fundamental human right, is regarded as a luxury by this group of people; only a few families are able to send their children to public schools. The absence of portable water has made typhoid fever a prevalent illness among the people. They source their water from a stream that has been stagnant for years; the color and stench it has acquired indicate how hazardous it is to its consumers. Good housing, which is something that every individual is entitled to, is lacking in Meta. Weak bricks, cracked and patchy walls and corroded zinc roofs characterize the majority of the structures these people call home, some of which have collapsed owing to the deterioration of the brick walls. The absence of toilets in most dwellings has driven the residents to practice open defecation. This, along with garbage left out in the open, pollutes their surroundings.

This year's essay competition, like previous years, highlights the relevance of social research in architectural design, urging architecture undergraduates to collaborate with social art students. Following this year's instructions, I chose to work with my sister, a social arts student at the University of Ibadan and we were able to come up with a successful essay proposal. The next stage of the competition, essay writing, required us to form a team in order to explore our ideas. We highlighted the professionals needed to carry out our proposal: a community researcher for the study and a land surveyor to examine the chosen site. We contacted a few of our acquaintances and six of them volunteered to join the team: a social worker specialized in community research and a land surveyor, both of whom were graduates of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, the rest were youths residing in Meta. We assembled the team and held a meeting to discuss the tasks that each member was to perform and how they were to be carried out; we prepared for the community research during this process.

The Pre-Design Phase

For the research, my crew and I needed to look into Korukoru's downtown area to discover more about this group of individuals. We went on multiple visits, interacting with the people and making new acquaintances. On every visit, we took along with us the community map, which we obtained from state's urban planning, marking out every place we had been to. While on one of our visits, we came across a large area of unutilized land that extended beyond Meta, to the outskirts of Korkoru. Its location made it perfect for the project. We measured the area of the rectangular site that belonged to the Baale, the community chief, and it was 19,440 m2. Its size permits the provision of adequate housing for the desired population while also allowing for future growth. Its closeness to the settlement fosters community involvement while also making building supplies and resources easily transferable. We presented the proposal to the chief, after which we were able to acquire the land which the land surveyor later examined.

In our search for financial support for the project, we presented the proposal to the community chief, who offered suggestions on how to go about it. We compiled a list of bodies from which we might seek aid and the state government was at the top of it. Although the state is rarely the driving force behind shelter finance initiatives, it still has a powerful influence on whether low-income groups can get good quality housing. Firstly, its access to the state's revenue enables it to provide the majority of the project's funding, sufficient to cover the cost of construction materials as well as professionals participating in the project's execution. Secondly, its impact on land markets and the potential for land tenure regularization in informal settlements, as well as the extension of infrastructure and services to previously squatter camps, creates an ideal environment for providing loans for upgrading. Other minor aspects of the project's implementation will be handled by financial assistance from the local government and private groups. We got feedback from few private groups that were willing to help after they received the emails we sent to them.

With the help of the community researcher, we were able to select an ideal method for the research, which was a survey interview. A thorough review of existing literature was conducted before carrying out the survey. Using stratified random sampling, 30 residents, each from a different family, were selected and a six-part structured questionnaire was used to conduct face-to-face interviews in their homes on weekends; this was done by the youths who volunteered to join our team. While the rest of the team helped with the interviewing of the respondents, my sister and I carried out personal observations on the residences of these people; photographs and notes were taken as a form of record. We observed that the houses existed in a simple rectangular shape in which one quarter of them were single-family dwellings while the rest were multi-family housing, also known as the "Face Me, I Face You". The multi-family housing, which consisted of two rows of four to seven rooms opposite one another, housed multiple families. The single-family housing, which had tiny living rooms and bedrooms, housed just one family.

As a consequence, the first section of the questionnaire, which comprised demographic information about the respondents, revealed that the majority of them were over the age of 30. The second segment result showed that the vast majority of families in Meta are compound households with more than eight members. The age distribution in these families is vast, meaning that each member of the family is likely to be of varying ages. According to the third segment, the majority of the residents pursue subsistence farming, while the remainder engages in hawking and junk trade. In the fourth part, the majority of respondents expressed a preference for smaller homes with fewer spaces. The questionnaire's last component, which included the results of a series of open-ended questions, revealed that the majority of the residents were experiencing poor lighting and thermal discomfort in their homes. These details were to be used in the final design.

For the next phase, a strategy was developed to provide community participants with the opportunity to engage in a process of choosing appropriate designs that meet their needs. We prepared an interactive session in which twelve Meta residents aged 30 and above agreed to participate. The workshop was designed in such a manner that each participant had an equal say in decision-making by creating an atmosphere of open communication. We created a number of design sketches as well as a collection of construction examples, each of which belonged to a distinct category of interest, such as dwelling type, shape, space, site arrangement and building materials. Each participant received a set of these materials for use during the interactive session. The two-hour workshop was held in an empty structure in the town square. Throughout the process, participants learnt about each other's values as well as became aware of the meaning conveyed by different buildings. At the end of the workshop, the input from the workshop and the findings, were translated into quantitative data and five of the participants were chosen as a committee to supervise the design so that it is consistent with their preferences.

'A Design for Flexibility'

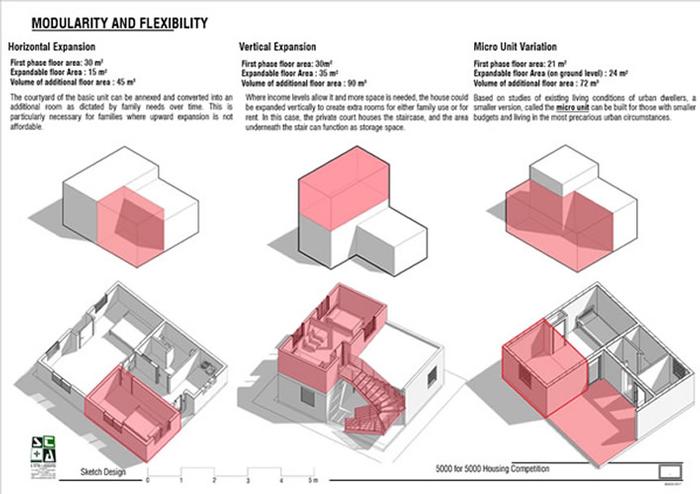

"Architecture is not static, but an ever-changing phenomenon that is constantly responding to its environment and the users who occupy it," Alma-nac stated. The ever-increasing population in various societies has resulted in a higher demand for housing, which has gradually altered the initial purpose of housing from providing shelter to a means of investment. This rapid increase has put the housing sector on the verge of collapse in terms of its ability to accommodate the growing demand; sufficient buildings are likely to become inadequate in the near future. Client preferences change, as do their needs for space innovation, resulting in the constant modification of available spaces. As a result, our design is aimed at controlling and managing the deficiencies that are likely to occur in the future. It is a design for flexibility, one that can easily be modified to suit both short-term and long-term needs of its users and a design that will promote socialization and eliminate poverty by embracing the revitalization of local industries. In accordance with this thinking, and in pursuit of maximum simplicity, we envision our intervention as consisting of three important components: building materials, design layout, and passive design.

Building Materials

The flexibility of designs is greatly influenced by the materials used in construction. To allow for quick adjustments and modifications, flexible materials that can be easily acquired within the neighborhood will be integrated into the design to save on construction costs.

Aluminum: Aluminum is a low-cost alternative to consider for building projects. Due to its light weight, durability and significant design flexibility, aluminum roofing sheets will be incorporated into the design.

Interlocking Bricks:Interlocking mud bricks uses less cement mortar during wall construction and allow its components to be easily demountable. This promotes design flexibility by allowing for simple changes.

Modular wall systems: modular wall systems will be employed in interior partitions that will consist of folding doors constructed with closely arranged treated bamboo panels inserted into timber frames. This is to accommodate temporary and permanent alterations that are likely to occur in the usage of spaces by the residents.

Raft Foundation: A raft foundation has the ability to accommodate up to ten floors. Mass concrete of 1:4:8 will be employed in the design of the raft foundation to accommodate the vertical expansion of structures.

Ceiling and Flooring: Terra-cotta tile is one of the top things the market has to offer when it comes to environmentally friendly building materials. The production and installation of terra-cotta flooring tiles contribute to its sustainability, making it an excellent choice for flexible designs. Bamboo is a popular plant in Oyo state that grows fast and has a number of desirable properties, including high flexibility and the capacity to be transformed into any shape. The use of jointed bamboo panels for ceilings, will allow for easy modifications and will improve stack ventilation within spaces.

Design Layout

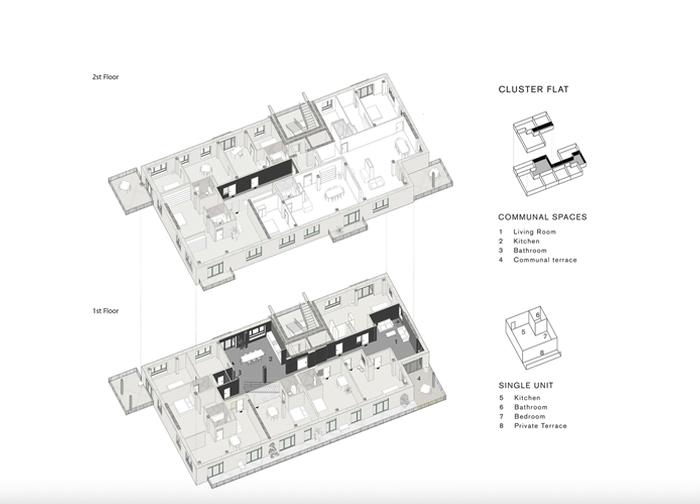

Dwelling Type: In order to accommodate all family types through the design, there were two proposed dwelling types: clustered and single units.

The Clustered Dwelling: This type of dwelling incorporates both private and shared spaces to encourage social interaction. The communal spaces for the first prototype include a large kitchen connected to a dining area, a bathroom and a large porch connecting to the rooms. Each family occupies one of these studio apartments which are the private spaces. In the second prototype, each family has their own kitchen and bedroom, but they share a large porch and bathroom. This very simple layout was influenced by the room-kitchen sample that some of the workshop participants selected.

The Single Unit: In this dwelling type, families have their own private living rooms, bed rooms, bathrooms, kitchens, and terraces.

Site layout: For the site layout, similar prototypes adjacent to one another, will form a block. The smallest unit in the neighborhood will consist of two identical blocks, spaced 3 meters opposite each other. This can serve as a communal space for the occupants of the blocks. A cluster of eight of these smallest units will form the neighborhood. There will be a large plot of 441 m2 at the center of the neighborhood that can be used as a community space. Pedestrian walkways will connect this plot to the adjacent blocks.

Passive Design

The use of louvered windows placed in opposite walls will enable maximum lighting and cross ventilation. The ceiling, constructed with bamboo panels, gives room for stack ventilation. The use of mud bricks which are good insulators and extended eaves of roofs will keep interior spaces cool.

The Post-Design Phase

Community involvement is essential in creating a sense of responsibility towards the welfare and growth of every individual. People for whom the project is intended will be involved in the implementation. Professionals in engineering and construction will plan workshops and informal training to prepare the individuals for the jobs they will be allocated in order for them to carry out their tasks efficiently. They will support and also learn from one another and this will strengthen their bonds. Affordable and low-cost housing options will be investigated and estimated by a Quantity surveyor and local industries will be revitalized as a result of the initiative. Sanitation campaigns and maintenance programs will create a sense of responsibility in the residents. A post-occupancy evaluation will be conducted to determine the status of the project and also broaden our understanding of better options to addressing housing problems.

Over the last few decades, people in hundreds of neighborhoods and rural regions throughout the world have come together to create their own community-based groups to address concerns that the government and commercial sector have long overlooked. This questions the essence of the architect whose responsibility is not limited to designing for clients but also in promoting societal transformation. His participation in communities and community groups is commonly viewed as a solution to a range of societal challenges and also an effective means to meeting community needs. In ensuring that these needs are met, design professionals must do all in their ability to deliver design solutions that are less about their designers and more about the representation of their users. This can be acieved through the direct involvement of people in the co-design of their spaces; participatory design.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |