[ID:4433] Economic Architectonics: Local Initiatives for Live/Work HousingEgypt “(Traditional waste management systems) spring from organic relationships between the people who run them and their city...They provide the poorest and most destitute segments of society with incomes, livelihoods, trades, occupations and economic growth opportunities which no other sector provides.” [1]

The Coptic Christian community of Hay el-Zabaleen (the garbage collectors’ neighborhood) is the oldest and biggest settlement of Cairo’s garbage collectors. The Zabaleen of Manshiet Nasser collect 40% of Cairo’s waste, sorting and recycling up to 85% of what they collect [1]. Their operations are a testament to the sheer amount of lessons that informality can teach planners and social scientists alike. Their informal economy possesses leverage to enhance their built environment, highlighting the central position of the Zabaleen’s dwellings in containing and supporting social and economic patterns; labor and consumption intimately combine to form the kaleidoscope that is Hay el-Zabaleen.

Economic Architectonics proposes the architectural manifestation of the community’s economic (and under the siege of neoliberalism, therefore social and political) habits to circumvent the developmental obstacles that face Cairo’s informal communities. By employing local initiatives, the residents can practice democratic rule in the design and construction of their live/work housing. While co-housing remains a lucrative model for many low-income users around the world, incremental live/work housing in the Global South can encompass the merits of the former while ensuring the sustenance of its communities.

Through a critical analysis of the history of Hay el-Zabaleen, the essay proposes a transdisciplinary model for Economic Architectonics. Reflecting Lola Shepard’s stance on “architecture as a research vehicle,” we rely on first and second-hand qualitative research to paint an intersubjective image of the community’s woes and potentials [2].

Politics of Blame, Exploitation, and Marginalization

While Covid-19 put all essential workers at risk, the H1N1 epidemic was riddled with more decisive discrimination. In 2009, the Egyptian government’s response to the “swine” flu (H1N1) epidemic highlighted the long-established inequalities that relegate the (Coptic Christian) urban poor of Cairo as perpetrators of disease, social unrest, and economic snag [3]. The brazen culling of Egypt’s pigs was detrimental to its Coptic garbage collectors that depended on the animals to complete their complex recycling systems and to generate marginal revenue from selling pork [3].

The government’s oppressive measures underscore the political, economic, and sectarian scrutiny in which the Zabaleen live and work. Kuppinger argues that pig culling was just one example of the “longer conflict over rights, territories, access to waste, and urban economic organization” that the community endures with authorities [1]. The operation was a calculated measure to stifle the garbage collectors' livelihoods and reinstate neoliberal pursuits that aimed to transfer their labor and revenues to global corporations [1]. In the 1980s, the government turned to establish formal high-cost solutions that required high-tech operations, deeming the Zabaleen’s operations—in place since the 1960s—backward, informal, and in need of regulation. Instead of developing the Zabaleen’s operations, the government ignored their central role in keeping the city in function, replacing them with foreign for-profit waste collection companies [1].

“Formal” and “informal” are adjectives often used by the authorities and media to decide who is worthy of stable livelihoods, where the former always has the upper hand. Despite the failure of the new waste system, only in 2008 did the Zabaleen resume their position in Cairo’s waste management system, working along with the private companies. It took years for the government to admit that the companies were not equipped to face the reality of Cairo’s streets, barely achieving a quarter of the Zabaleen’s recycling rate [1].

Like almost all of Cairo’s informal settlements (estimated to house at least half of the city’s population), Hay el-Zabaleen’s tenure and access to resources are perpetually precarious. The community sits between Cairo’s biggest park and an upscale gated community reserved for Cairo’s elite, subjecting the community to constant threats of relocation to the fringes of the metropolis. In the early 2000s, under the guise of development, the government proposed to move their recycling operations to Qattameya, 25 kilometers from the city center [1]. Many speculated that the proposal was the first step in removing the community altogether. With the current government’s violent expansion of infrastructure and real estate, coupled with the erasure of the Maspero triangle and districts 6 and 7 of Nasr City, the threat of relocation is still palpable today in the streets of Hay el-Zabaleen.

Through our fieldwork, we have outlined multiple community and infrastructural needs. There is no explicit pattern of separation between areas of work and households, for they are very much spatially intertwined. This live/work spatial formation is pivotal for economic sustenance and viability. However, it poses direct health and environmental challenges. Waste management processes generate a considerable amount of toxic gases to which the community is continually exposed. Moreover, exposure to potentially toxic materials during waste separation leaves the community vulnerable to health hazards that are minimally addressed through local clinics due to limited donations.

Until recently, the community was mainly reliant on rickshaws pulled by donkeys or horses and was forced by the state to abandon these modes of transportation for modern and contemporary vehicles. As a result, the community has adopted trucks and toktoks (small two-wheeled vehicles) as modes of transportation that are damaged by the unpaved and poorly drained streets [1]. The infrastructural incompetencies harm and decrease the value of the transportation assets used in waste collection and management processes. Therefore, one of our primary objectives in the project is to build sufficient infrastructure in the streets and functional drainage systems to protect economic assets and operations.

Collaborative initiatives to introduce less hazardous processes for labor-intensive waste management are highly encouraged. These initiatives will not be designed to introduce new practices; instead, they will be done to create new resources that could potentially lessen the level of exposure to hazardous and toxic substances. Many women utilize discarded textiles to design rugs, carpets, quilts, and blankets. They are usually confined to working in specific spaces within the Association for the Protection of the Environment’s building (APE), a local NGO that has helped empower the community for the past 25 years, and prefer having crafts stations within their households [4].

Subverting Neoliberalism: Subaltern Street Politics

The process of designing and building housing for el-Zabaleen needs to emulate the resident’s negotiation and subversion of Cairo’s neoliberal forces. Bayat refers to these tactics as “street politics,” small acts of resistance that negotiate the bureaucracies the residents are subjected to [1]. The “art of presence” of el-Zabaleen lies in the nuances of daily living that make the most out of adversaries, allowing the continuation of their socio-economic patterns while avoiding confrontation with authorities. Popular action, driven by the community’s self-interest, slowly but surely encroaches on otherwise impenetrable power structures [1]. “Street politics” must be recognized and sustained if the settlement’s patterns are to be harnessed.

The community is centered around the St Simon Monastery. It is considered to be the nucleus of the community. The monastery was built in 1974, after the founding of the community in Manshiet Nasser, to provide educational opportunities, financial support, and religious guidance to the predominantly Coptic Christian residents [1]. The fact that the monastery came after the founding of the community in Manshiet Nasser underscores the interconnectedness of space and community and how, essentially, in the Hay El Zabaleen community, community and social existence predicates spatial establishments.

In the spirit of subversion, team members are expected to uphold the Zabaleen’s “art of presence” first and foremost, leaving behind personal preconceptions on the formal-informal dichotomy and any other philosophies that may stand in the way of giving the residents the first seat at the table. University students, unengaged in the government’s rhetoric and oriented towards producing knowledge and novel ways of bettering society, represent a viable way of recruiting project team members. With their access to intellectual resources (and the added incentive of producing research for their respective institutions), students from all over Cairo can contribute to the project's research, design, construction, and administration.

Turner goes on to suggest that “users should decide and (users) provide”; we are suggesting that this proposition can be taken further by asking sponsors to facilitate and negotiate [5]. The intention is to reduce dependency and reliance on outsiders and give the highest level of financial autonomy to the users. Although the 1980s’ World Bank-funded development programs failed to cover the infrastructure and housing needs of the community entirely, the financial models put in place proved to be effective. Long-term housing loans allowed the residents to improve the quality and size of their homes comfortably, thereby facilitating the construction of incremental multi-family homes. Additionally, sourcing construction materials and labor from the community itself allowed new business opportunities to emerge, multiplying the economic returns of the injected loans. As such, the Sawiris Foundation, one of the biggest donors of APE, can set up the loan program and facilitate monetary operations, leaving decision-making to the community first and the project team second.

Radical Democratization

Many scholarship and projects have been conducted in the name of participatory design since the promulgation of Turner’s writings by planners and development agencies. Indeed, his work has transformed how the World Bank approaches its urban development projects, but Turner himself remained skeptical of formal institutions [6]. Freedom To Build and Housing by People can be viewed as anarchist manifestos, as instructions for a value system that necessitates the creation of (informal) grassroots institutions for the exchange and application of knowledge [5-7]. Participatory design is not a boiler-plate formula for user-centric design, “but a commitment to the core principles of participation in design” [8]. In attempting to implement Turner’s lessons, these core principles can be summarized in the creation of a democratic knowledge-sharing infrastructure that is tangible, accessible, contextual, and creative. Participatory design for the Zabaleen is imagined to be a continuous and iterative process, powered by “design by doing” methods that include the application of mock-ups, pilot projects, and constant assessments [8].

Drawing on Madd Platform’s Maspero Parallel Participatory Project, a research project that aimed to provide bottom-up design alternatives for (the now demolished) Maspero Triangle’s investor-backed government development plan, the following steps for participatory research, planning, implementation, and evaluation will need to be applied [9]. The first is to conduct participatory research where, with the help of desktop research, public community meetings and workshops will be conducted to diagnose the problems and needs. In parallel, ethnographic research will paint the nuances of working and living in Hay el-Zabaleen, ensuring two-way participation by involving team members in the residents’ lived experiences. Secondly, participatory planning sessions will take place, where focus groups, pilot projects, feedback sessions, and community presentations will form the groundwork for the collaboration between the team and the community in preparation for the final designs.

Methodology and Collaborative Fieldwork

The research aims to empower and not to transgress. Considering waste collection is a labor-intensive process, integrating neoliberal ideals of technological change would be counter-productive. The community shares a collective fear of crowding out by large private sector firms offering the same waste collection services using advanced technological processes. We aim to provide the tools necessary to enhance labor-intensive processes that provide employment and income for the community and not substitute existing processes and spatial constructions.

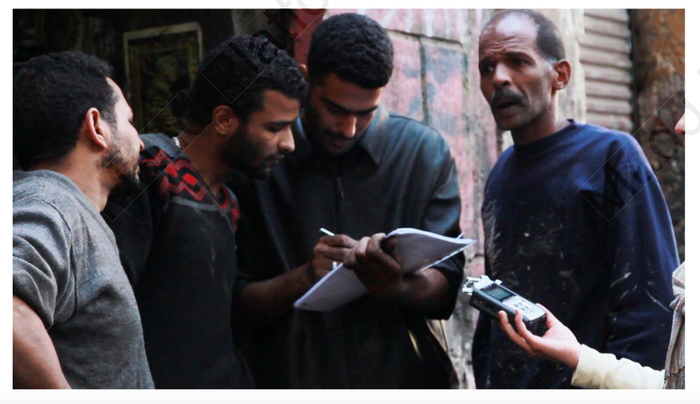

We paid a visit to foundational and communal landmarks within the area. Our primary mandate for pursuing fieldwork was to ensure that our research is collaborative, interactive, inclusive, and engaging. We interviewed a member of the APE, which plays an elaborate role in upholding and preserving particular communal and social ideals through their work in creating a circular economy, encouraging sustainable practices and craftsmanship, facilitating educational experiences, and providing medical care for individuals who work in waste collection, and are vulnerable to specific illnesses such as Hepatitis C. Our methodology is an extension of collaborative ethnographic practices, through which fieldwork becomes “a collaborative process between ethnographer and interlocutor”[10]. Contemporary theories of applied anthropology are centered around integrating “public anthropology” into the canonical concepts of social change. Through public anthropology, theory becomes externalized into forms of public engagement.

A set of questions did not predicate our fieldwork; instead, the predominant aim of the fieldwork was to understand what questions we should be asking. Our methodology incorporated a laissez-faire form of dialogue with our interlocutor. This approach feeds into a larger emerging contemporary narrative of applications of social theory, which advocates for a deconstruction of power imbalances between researcher and interlocutor and production of interactive fieldwork experiences through which the interlocutor becomes an agent of social, political, and environmental change. Questions that were covered in our fieldwork but require additional exploration include:

Not only will the final housing units reflect the economic, social, and material patterns of the community, but they will also employ local initiatives, a model of self-governance and mobilization borrowed from Ibrahim and Singerman’s analysis of the work of “TADAMUN: The Cairo Urban Solidarity Initiative.” Local community initiatives point to the potential of extending Bayat’s “art of presence” into independent entities of collective action, especially in post-revolution Egypt that saw the rise of Ligan Cha’biyya (Popular Committees) that filled the security gap left by the governmental vacuum in 2011 [11]. The implementation of this proposal would feature the introduction of community design centers, which will facilitate technical and design consulting for informal settlements. Community design centers and similar local initiatives encourage participatory governance and provide opportunities for post-occupancy evaluations [12].

Conclusion: A New Way of Designing, Building, Living, and Working

“We are not the protagonists. Architecture is just the background.”- Alejandro Aravena [13]

Economic Architectonics is founded upon connecting the built to the unbuilt, highlighting that community is the first resource needed to establish landscapes. This proposal sheds light on alternative narratives through which urban development can be envisioned. This narrative is particularly pertinent to communities of the Global South. Informal settlements of Greater Cairo are fundamentally united in their differences, and it is pertinent to recognize that each community defines itself differently in terms of its own urban and social existence. Amidst grandiose urban agendas of homogenous cosmopolitan development, it is vital to shed light on how contextual non-linear urban development, powered by collaborative and creative research, can be the model for designing, building, living, and working in the city.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |