[ID:4199] Mediums to ChangeIndia Mediums to change

I live by the landfill

Sabir, 38, wakes up to the azan. In his morning prayers, he wishes to find something of value while scouting the landfill. Delhi disposes two tonnes of its waste at Bhalswa, and hundreds rummage it for daily sustenance. Today, Sabir has not been as lucky. Heaving a sack full of plastic bottles, he makes his way down the 60-meter high mountain of guilt. Later this week, Sabir's family will segregate these collected recyclables, and sell them for a meager profit. Families like Sabir's lie at the informal end of Delhi's waste management system. Although carrying out essential work, they are subject to deplorable habitats. Undignified housing, along with severe health and safety hazards make up for the worst living conditions in Delhi.

I live a mile by the landfill

"Are we here yet?" I would giggle when looking at the gigantic brown mountain on a family trip to the hills. Later, rolling up my windows to its rotten stench, my excitement would turn into discomfort. The Bhalswa landfill earmarked every road trip we took. Our interests lay in what was ahead of course. Taking a halt at Chandigarh, we would admire the bare grey concrete cutting through the blue sky. "This was all Le Corbusier's doing." my mother would tell me. The idea of a single person laying bare an entire city and designing it felt very much like the Lego I would play with. Later in my rebellious teenage years, I grew to idolize Ayn Rand's, Howard Roark. The tale of the one individualist architect working on his own right tempted me. Soon, excited to wage my own war against the world, I joined architecture school.

"(Architecture Schools) are wholly unequipped, at least during the formative years ... to impart any social ethics to future generations of architects." Nathan Koren, 2000

Today, I am nothing but somber when relating to what Nathan Koren wrote for his essay, a whole two decades ago. My school experience has been no different. Before learning to think, we learned to draw. Why architecture? Because we had chosen to be architects. Who were we designing for? We never knew. Design discussions ranged everywhere from the metric, programmatic, and aesthetic. "All kinds of styles make it into the design studio, except lifestyle." puts Priyanka Shah, 2003. The debate on the built never encompassed the living, and such is the pedagogy today. With this, I ask the reader, how can emerging architects learn to respond to the community?

Unlearning

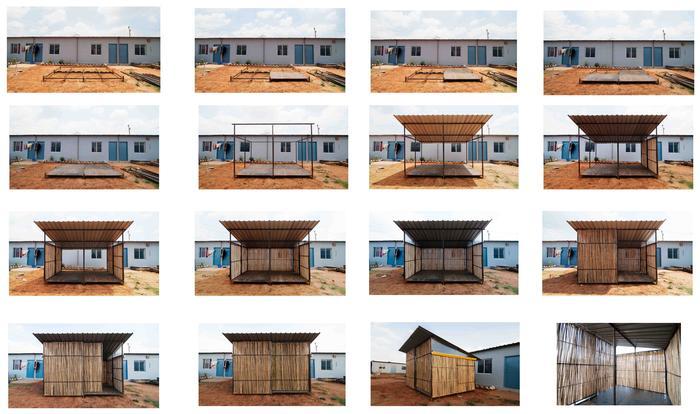

In the summer of 2017, while scrolling through social media, I came across a rather unusual post. "We’re building an anti-demolition school for 250 students at Yamuna Khadar, Delhi. Come Support!" The authorities bulldozed Van Phool School — a permanent hence illegal building. Fearing their children's education, people at Yamuna Khadar set up a school under the sun. Why architecture? It was the only means. Seeking a resilient solution, Adbul Shakeel, a community activist, approached two young architects. Swati Janu and Nidhi Sohane’s design brief resulted from several consultations with the community. Modskool was born out of necessity yet envisioned for dignity.

Modskool’s construction began with a few volunteers assembling its bolted steel frame structure. Considering comfort requirements and durability, they had installed a weatherproof corrugated sheet. The genius in the ease of assembly was a future consideration of dismantling. The idea of a community built school took me by surprise and I decided to volunteer in the program. It took me a bit to understand, but we were soon weaving bamboo screens that were to form the building's skin. Through techniques that anyone could carry out, the construction engaged the community. Very often, the team would gather around to discuss a way forward. The means to Modskool was both collaborative and flexible. Modskool's designers were no all-knowing maestros but facilitators to a cause. In the community-driven process, some even took ownership of the project. A few volunteers emerged as facilitators distributing responsibilities in the construction process. Involving over 50 people, it took only three weeks to realize the project.

Soon, Modskool started facilitating the education of a community for years to come. Modskool led to the formation of Social Design Collaborative, SDC. The community-driven design, art, and research practice aims to provide design for all.

Dream all you can

It was through Modskool that I learned of architecture as a social art. Architecture had the potential to be a catalyst to change and make lives better. Alas, back at school, we only worked on hypothetical situations ignoring worldly concerns. Fearing the limited state of practice beyond, architecture school encouraged us to conceptualize. "Dream all you can, for all you'll do upon graduating, are toilet drawings." our superiors would preach. Were we all destined to the same exploitative, unimaginative journey? The answer came through Alok Shetty, a young architect, who works to dispel the myth. To him, concepts on paper are ideas for the future.

Simple Ideas to Innovative Buildings

Shetty was still a student when a competition invited him to design a hospital in his city. To educate himself, the 19-year-old began extensive research. To learn of its workings, he immersed himself in the city's hospitals. In identifying problems in current designs, he interviewed doctors and hospital staff. A key insight for Alok was Occam's Razor - the simplest solutions being most often the right solutions. The architect sought an architectural implication to the medical concept and founded Bhumiputra. The designed hospital was the first in the country to receive international accreditation. Bhumiputra has since grown to design cultural centers, corporate offices, and more.

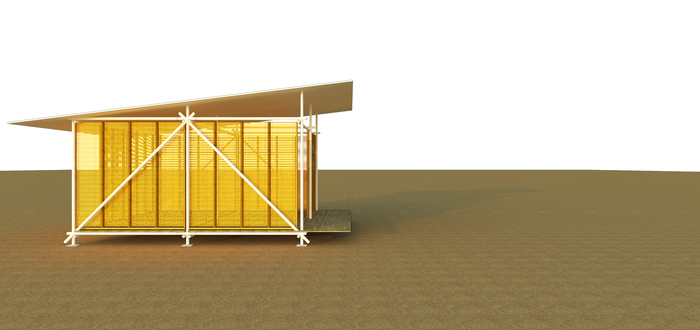

For every new project, Bhumiputra decided to sponsor the education of the underprivileged. The initiative brought the team closer to deplorable living conditions in urban slums. Eager to make people's lives better, the practice took on the challenge to design for change. The identified settlement was a community of construction workers living by the cybercity. It was ironic that labor skilled in construction was subject to living in shanties. Bhumi designed with the workers in materials they were comfortable working with. Steel scaffolding pipes and shuttering wood became the design language. The evolved prototype was assemblable in a couple of hours and cost less than $300. Years of testing evolved the prototype to meet its users' needs and challenges. The result of a passion-project was a potential solution to solve a wicked housing crisis.

Observe and Act

Alok's example sheds light on how social architecture can thrive within existing systems. What is critical, as Jan Doroteo puts it in his 2017 essay is "for the architect to observe, listen, and ask."

In the last year, beset by the pandemic, my architecture education has seen a pivotal point. When the pandemic distanced us from the world, it brought us closer to our homes. It has brought forth a new horizon to design exploration and thinking. I've spent my time walking around and observing my own neighborhood. While I was hoarding rations, Sabir stood in a mile-long queue at Bhalswa hoping to get cooked food. What could I have done to make a difference here?

In facilitating a network of young leaders acting for change, three agencies; the Center for Living City, the Urban Design Collective, and the National Association of Students of Architecture, launched the Observation and Action Network, OAN. The Network envisioned a national competition seeking bold responses to local problems. Sensitized to the plight of Sabir and others, we took our pencils to zoom meetings.

In serving the Community

What could we as young students do in making peoples' lives better? All with a mere $500 the OAN grants offered. We started out with our academic inheritance - tumultuous mapping. The resulting drawing said two things. First, the landfill was a hazard to the people. Second, there is an open space problem in the colonies. Could a conversation with a local not have given us that? Hence, interacting with people, not drawings, we ventured into the place. In our bottom-up process, people began addressing their concerns. Children needed a place to play, the youth sought employment, and the adults had to walk a long way for a bus to work. Interestingly, space underneath infrastructural pipelines lay unutilized despite being accessible. This was the birth of Chhav - our project for dignified open spaces at Bhalswa.

An architectural intervention would serve as an immediate forum for the people. Our elegant solution was to create a shaded space underneath the pipelines. Chhav would be a place in the shade - for the community, built by them. Learning from Modskool, we knew small interventions could have a great impact.

“It is your responsibility to put public money to best use,” cautioned Alok Shetty, when discussing Chhav. Uncertain of our idea's implications, we tried out a pilot. Our first prototype for the community space was to not be cast in steel but experienced. On a hot, sunny afternoon, we held a community meeting under a tarpaulin stretched onsite. Rendered in yellow, the place transformed itself. Soon enough, people followed and we struck into a conversation. "What if we could have evening school here," suggested Raghav, 12. "We play cricket in the ground, and it gets hot," exclaimed Suraj, 15, "Could we use the space as cricket stands." he inquired. "There's more! If we clean it, we could also host functions here," commented Yogesh, 35. “We, women, are afraid to pass by the ground since it’s prone to antisocial activities. It would be much safer if there were people here.” lauded Rani, 34. The community's solutions became our design brief, and Chhav leaped forward.

Setbacks

Our initiative at Bhalswa has been our unlearning as upcoming architects. It has taught us to believe in reality over theory. In evaluating our ideas with the community - the end-users and owners of the product. Consulting with the people, we have seen steady growth in community attendance. Starting with four people to forty people today. On the downside, with no one always committed to the project, work has often lost momentum. The community has to work a living, and we have our own academic deadlines. This has brought us to question our own model for practice. We can only choose to volunteer our services since we are in the academic terrarium. What comes after?

In today's paradigm, good design goes associated with an equal charge. This presents a dichotomy. Architects aspire to make a difference. Yet, they are inaccessible to the communities that most need them. If not levying a fee, where was the needed money to flow from? How else could we make our pro-bono enterprise sustainable?

There is only so much difference a grassroots initiative can bring about. In a nation of 1.3 billion people, affecting 130 will not amount to considerable change. Can architecture aspire to service communities at large? How could we make our rooted practice scalable?

Looking back to look forward

Architects can best serve communities when they develop a sound praxis. One that is all; social, sustainable, and scalable. Furthering our practice involves asking the right questions. Answering these involves an investigation of the same precedents that shaped them - Social Design Collaborative, and Bhumiputra.

Collaboration

In answering scalability, Social Design Collaborative and Bhumiputra practice collaboration. As a decentralized approach, the method eliminates a top-down, principal-oriented practice. It allows for like-minded individuals and organizations to come together and work towards shared goals.

SDC believes that collaboration is a key way in their objective of Design for All. In only a few years of working, they have created a need-based approach for the community. Their most recent contribution is a manual on 'Street Vending in times of Covid 19.' The interactive document discusses the virus and the reasons for its spread. It also provides suggestions on how informal vending can adapt to precautionary measures.

Developing their housing project, Bhumiputra started tying up with local organizations that had shared goals. Collaborating alongside Mahesh, they set up a local school and health clinic. Then with SELCO, they facilitated solar lights and resources with a pay-per-day model. This is also closely linked to the model for sustainability - ecosystems thinking approach.

Ecosystems Thinking

Today, their social practice is a part of Parinaam foundation's Chote Kadam - small steps. The project manifests through Ujjivan Small Finance Bank's Corporate Social Responsibility. In the last three years, it has affected over 1.2 million lives through 164 projects. The venture has spent over 1.1 million dollars on social welfare, with a range of projects from housing, sanitation, education, and infrastructure.

SDC’s answer to sustainable practice is an ecosystem that is open to all. The knowledge that the collaborative generates is not proprietary and specialized. Instead, it is open-source. Anyone seeking to develop solutions akin to SDC can find their designs and work ahead. An example is Modclass, where Modskool's design adapted to extra space requirements during the pandemic.

The two practices bring out holistic community interventions for social welfare. Yet, their method isn't the mass implication of factory-made ideas. At the core of their work lie community-driven approaches towards a designed solution.

Architecture for All

In essence, the means to a social architecture have a simpler implication - working together. For architecture to be social, it is imperative to work with the community. For the practice to be sustainable and scalable, it is important to work with others. Architecture for all is architecture designed by everybody. What exactly is our role as architects? Isn't it to be a medium? A medium to change!

PostScript

We live by the landfill.

We must understand that the landfill, though associated with all its stigma, is our very contribution to the city. Our initiative with Chhav is but one named initiative towards change. It is time for us - Sabir, you, and I, to stand together as one. The future is about working together as collaborative ecosystems. For when we are a part of a larger community, we alone do not have to concern about serving it.

In the words of the late American Educator, Hellen Keller:

"Alone we can do so little; together we can do so much."

Works Cited

Norman Koren Photography: Images and Tutorials, www.normankoren.com/Nathan/bprize.php.

Alok Shetty, Out-of-Box Architecture

https://youtu.be/x3c9aRi0omo

Ujjivan, ujjivan.com/csr-chote-kadam.

“Berkeley Prize Essay Competition.” Berkeley Prize 2003, www.berkeleyprize.org/competition/essay/2003/winning-essays/priyanka-shah.

“Berkeley Prize Essay Competition.” Berkeley Prize 2017, berkeleyprize.org/competition/essay/2017/winning-essays/jan-doroteo-essay.

“Chhav.” The Center for the Living City, centerforthelivingcity.org/oanfellows2020-chhav.

Dickinson, Duo. “Why Architects Don't Do More Pro Bono Work.” Common Edge, 6 Aug. 2016, commonedge.org/why-architecture-doesnt-do-more-pro-bono-work.

Jon Astbury | 24 January 2020 Leave a comment. “ModSkool for Squatters in India Can Be Dismantled to Evade Bulldozers.” Dezeen, 30 Jan. 2020, www.dezeen.com/2020/01/24/modskool-social-design-collaborative-squatters-india/.

“Livelihood: Parinaam Foundation.” Livelihood | Parinaam Foundation, www.parinaam.org/chote_kadam_to_community_initiatives.html.

“The Reserve: Archive of Top-Reviewed Essays: Berkeley Prize Essay Competition.” Berkeley Prize 2021, berkeleyprizecompetition.org/endowment/the-reserve?id=1493.

“The Reserve: Archive of Top-Reviewed Essays: Berkeley Prize Essay Competition.” Berkeley Prize 2021, berkeleyprize.org/endowment/the-reserve?id=2023.

Shah, Palak. “ModSkool: A Modular Tool, Twice Embraced a Children's School.” World Architecture Community, World Architecture Community, 2 Feb. 2021, worldarchitecture.org/article-links/egvfh/modskool-a-modular-tool-twice-embraced-a-children-s-school.html.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |