[ID:4069] The Billings SceneUnited States Housing is a basic necessity that any individual must have to survive no matter the community, culture, or climate. As the pandemic began to make its way into the United States, the homeless shelters were faced with the harsh reality that their infrastructure would prove insufficient to have the ability to protect the community. Some shelters began to limit the number of people coming in, especially during meals when people are not wearing masks and are more likely to infect others. Some residents even decided that sleeping outside would be safer than sleeping in the shelter. This resulted in them leaving the shelter altogether (Mara Silvers, Montana Free Press, July 2020). The issue of homelessness seemed impossible to tackle prior to the Coronavirus, struggling with overcrowding and lack of resources as homeless shelters are generally non-profit organizations. Now, it is even more complicated as shelters must make the decision of whether they must turn away individuals who are exhibiting symptoms of the virus to protect the safety of others.

In Billings, Montana the issue of homelessness is evident. Often when walking in a park or near an underpass I will come across old clothes and blankets. I often see people standing on street corners asking for money written on a piece of cardboard and it’s sad to see knowing the weather in Montana is harsh. Our seasons tend to be polar opposites with sweltering summers and stinging winters. In recent years, the public-school system has noticed an alarming number of homeless students that have existed under the radar. Children are much harder to spot, The Billings Gazette describes them as “almost invisible” as they usually live on a friend’s couch or in their car. They are not out in the open loitering downtown or standing on the corner. Unfortunately, these children often struggle academically and are less likely to graduate high school, but much younger groups are also affected. In the first month of the fall 2019 school year, 117 homeless students were identified in grades Pre-K through 8th (The Billings Gazette, October 2019). There is a program in Billings, Montana called Tumbleweed that offers many great services directed towards young children and families in need. In 2018 they had served 394 kids under the age of 18 and a total of 693 ranging from ages 10 to 24. Not only do they tend to the symptoms of homelessness, but they also help to cure it with parenting classes, short term counseling, and much more. They describe themselves as, "Founded in 1976, Tumbleweed is a non-profit, community-based agency serving homeless, trafficked, runaway, and otherwise at-risk youth and their families and support systems” (Tumbleweed Program.org).

As a student in architecture school, I want to work at the Community Design Center, CDC, when I am in my 4th year. The Center has had many great design ideas and projects since the 1970s. I have seen engagement with many cities in Montana for the past few decades. Steering the community work towards my hometown would open endless opportunities for the CDC to create new design ideas and put them to the test. I believe my time working there will teach me how to push designs to the limits while working on a tight budget. The CDC, in collaboration with Tumbleweed, could, perhaps, identify and address ways in which student-driven architectural design projects could help the homeless community in Billings. Quite a few students who are from Billings attend my school of architecture, so there is a possibility that there would be students who have seen the struggles first hand and possibly experienced them. Those could be the students who would help find fitting solutions to tackle community struggles.

Tumbleweed already has many ideas to tackle homelessness. Duo Dickinson, an architect who participates and advocates for pro bono work based in San Francisco, discusses the fact that most projects have such a small budget they cannot afford to pay designers that would create better spaces to meet the specific needs of the community. He also proposes that there is a lack of pro bono work because there is a lack of professional focus. Many top architectural firms claim to participate in the “1+” program where many firms donate 1% of their billings to non-profit work. Although many firms report that they do not reach this goal and instead only a fraction of it. Dickinson describes this as barely meeting a fraction of a fractional goal. This is why pro bono work by architecture students would be especially beneficial. It provides more learning opportunities and real-world experience for students while helping communities that cannot afford to hire professional help (Dickinson, June 2016). Especially since my school is close to Billings, they can get to know the community well to find more creative, efficient, and fitting solutions.

The lack of widespread professional focus leaves schools and student design centers to lead the way for pro-bono project numbers. Studios like the late Samuel Mockbee’s Rural Studio at Auburn University, the Yale Vlock Building Program, and the Studio 804 at the University of Kansas have been quite successful in that they have helped meet the local needs of the community. On a larger scale, they have not been incredibly impactful in the sense that they have not contributed to nationwide projects (Dickinson, June 2016). However, maybe that means pro-bono work does not have to be done by firms that are already very successful and have some money to spare. Maybe that means more schools or architecture should start developing community design centers. Often why pro-bono does not work for regular or small firms is because free work is not always an affordable or wise option if a firm can barely keep its heads afloat. This is why community design centers from schools could be a local and affordable option. Assistance and guidance from firms can help build relationships between the community and the school.

The importance of a design center knowing its community's needs is crucial. In the early 1990s, there was a collaboration with the Yale Vlock building program and Habitat for Humanity of Greater New Haven to make one house a year for the community. These houses would be designed and built by the students. At first, the student’s creations were fun and exciting. Habitat’s clients were excited to be able to have an enticing new home at an affordable price. As time went on, the board of Habitat for Humanity realized these homes required more maintenance than usual houses would and were developing security issues. This is the importance of knowing how to meet the people’s needs. These homes had some fine arts expression in them but did not quite help to meet the needs of clients. Duo Dickinson says, “In the cause of pro bono work, inspiration is not a bad thing; but building what you design is not desirable, it is absolutely necessary”(Dickinson, June 2016). When doctors do pro-bono work it is to potentially save someone’s life or improve their quality of life. Similarly when architects offer to do free or fundraised projects, they believe that they will be improving someone’s quality of life, or perhaps, saving it. Generous architects would not take on little or no pay work if it was not something they found to be of great worth outside of its monetary value.

After I get my master’s degree, I hope to move back to Billings to do my internship and eventually design as a licensed architect. After working at a firm for a while, building a foundation and my reputation, I would like to start a partnership with the nearby architecture school. It would either be my own firm or the one I am working at where I have built a strong relationship with the head of it. I would contact the community design center from the school I graduated from to discuss how working in Billings would provide vital and creative problem-solving skills for the students involved. This partnership would be working with upper-level students to collaborate with community members that need help with design projects. My hope is that nearby architecture schools would see this partnership as a way to solve issues within their community. This would create programs in other architecture schools to give their students opportunities to give back to the community and get real world experience. They could also benefit organizations that need help with design projects that are on a budget.

I would like my firm and many others in the state to work closely with this program. First and foremost, I want the relationship between the school and my firm to be incredibly strong. If there is not a strong foundation of trust, accountability, and humility then in the case that something goes differently than we expected I do not want the partnership to part ways. Then that will leave the homeless community and shelters on their own again trying to tend to the symptoms of homelessness and pick up the pieces of what remains after we tried to help. To help Billings, Montana we must remain consistent. If we are not moving forward each person lives another day unsure where they are going to sleep and possibly standing in harm’s way. The number of children living day to day without a consistent home is more important than a failed partnership. To build this relationship, I suggest we set up regular meetings a few times a month to review and examine our work making sure nothing slips through the cracks.

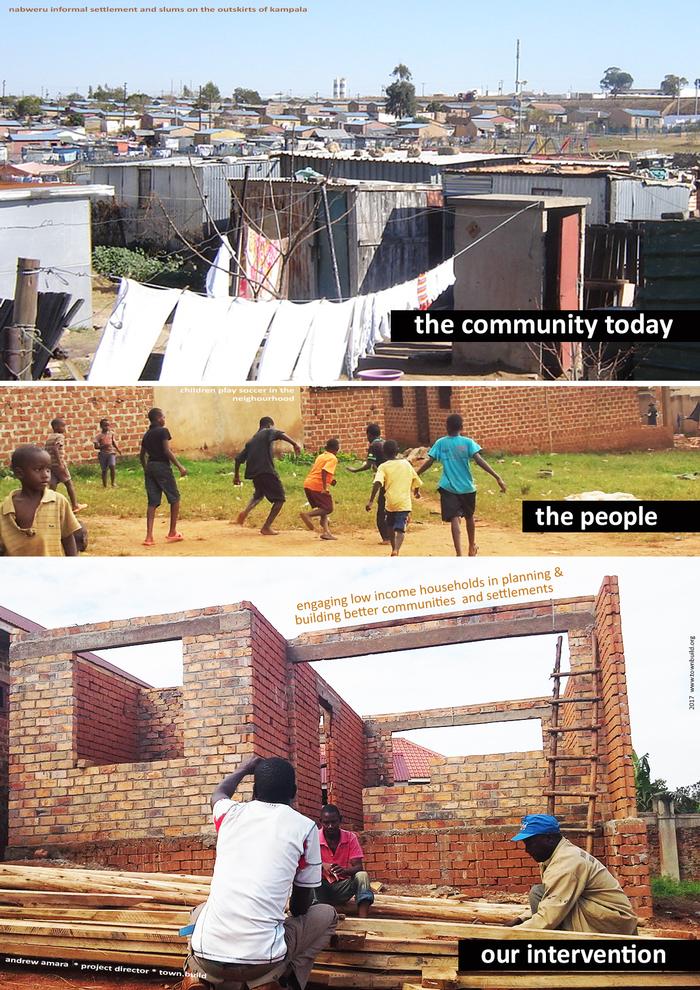

A former Berkeley Prize Essay winner, Travel Fellowship winner, and current committee member, Andrew Amara, discussed in the Berkeley Prize 20th anniversary response that his participation in the competition opened his eyes to how architects can have a large impact on the lives of a community. He continues to mentor students and try to show them “the importance of finding ways to impact society.” It is important that these programs be student driven. This is their opportunity to learn in the outside world and it is a good experience for students to get them away from a desk-tied education. Often architecture students find themselves stuck in the studio for hours on end. As crucial as design work in the studio is for these students, it is important that they get to know their designs are for a real community that exists outside the studio. A community that has its own complex systems, needs and controversy.

A critical strategy that the Rural Studio uses is community presentations. As designs develop, communication with the community must be closely maintained so they hold these about every six weeks. They use the discussion with students, clients, and stakeholders to address concerns and make better design decisions. This is one of the reasons that the Rural Studio has been so successful in its community. This is also what has helped them continue the program for almost three decades (RuralStudio.org). The input of the community members will build the personalization of the design to the community. For the Billings partnership, it would be important to involve those who can offer input about how to help the homeless children community. Involving Tumbleweed and some of the teens and kids they work with, as well as maybe some caseworkers who work with foster children. These reviews help to further improve designs of the students. It also ensures that even though this work is cheap in cost it is not cheap in quality.

Another consideration that the partnership must keep in mind is that not everyone in need of assistance in the community will have equal physical abilities. In making community projects it is important to keep those with disabilities in mind. It is not necessarily hard to meet ADA requirements, but it would be better to do more than the bare minimum. Meeting with those who have disabilities to use as consultants would be informing the team how to best design a project that will be user friendly to groups of people who will have a wide array of abilities or disabilities. The University of California Berkeley uses this strategy and their disabled consultants have brought brilliant input towards helping projects become friendly to all types of people ( Bruce W. Bassett, A house for someone unlike me, 1984).

Architects have the beautiful privilege of being able to change a community by changing the shape of it. By shaping neighborhoods, shelters, apartments, and much more, we determine how the flow of people will move through a space. We have been given the opportunity to use our ability to see the unseen and magnify it, fix it, or express it. As homelessness can be a complex issue, it cannot be tackled with a single solution. The key to helping any community become safer and consistent in housing people is to start small. It does not take one large non-profit organization or a collection of large firms donating one percent of their profits. It takes a passionate community to fix itself. This is because homelessness is not the same in every town. Each community must be researched and studied as well as the people must be understood and interviewed. The role of architects is critical as we have the ability to see the problems and design effectively to solve them. We can go to the root of a problem and solve it. Even with our unique abilities there are still a multitude of variables that can unfortunately hinder or even stop projects altogether. One of the biggest contributors to projects besides an architect’s passion is money. Peter Aeschbacher, a Pennsylvania State University professor says, “If the conversation is really only about the infrastructure, then we have missed the opportunity to have the larger conversation about how we choose to manage the world,” he adds, “And that is at the heart of the community design movement”( Alaina Johns, Community design centers help reshape the state, October 2017). The idea of using students from schools with community design centers helps to decrease some pressure regarding money without causing a project to lose it’s quality. The partnership with the community design centers will use a rigorous process of reviewing, consulting, and improving designs. Along with regular reviews, we would invite other architects in order to get a wide variety of accountability. These students research and communicate with these communities to reach solutions to specific needs that will improve the life of any person no matter race, religion, or disability. These strategies follow in the footsteps of The Rural Studio which has shown to be successful for three decades. The partnership between my firm and the community design center is a small start but it is just what is needed to make a difference. I hope to plant a seed of generosity in these students to implement the importance of professional passion to end homelessness.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |