[ID:3293] Cycles of Recovery: Finding Abundance in the AbandonedIndia We often like to imagine a world with no limits. A world, where our actions have results but no repercussions. A world, where we never run out of resources. Where the riverbeds never run out of sand, where the seas never rise, and the forests replenish themselves; a world, where climate change is a myth. But then, we are rudely interrupted by reality. We realise that this world in our heads is an unreachable fantasy. Climate change is undeniable, and we live in a world where our actions have dire consequences. A world where our reserves are steadily depleting, and will soon face serious deprivation of resources. Sustainable development has been put forth as a solution to this critical issue. Navigating through discourses of sustainability, we came across many instances which involve resource management and conservation. All through our education, sustainability meant the five R’s – refuse, reduce, reuse, recycle and recovery. However, this understanding is limited to just plastics and bottles, gas and petroleum. This perception of sustainability is rarely ever extended to the field of architecture and construction.

This perception is quite evident through common architectural trends, which all revolve around creation. For example, each well-thought–of design, carefully orchestrates the construction processes, takes care of the functional requirements, and only dwells deep into shaping the perfect spatial experience. ‘Building’ is plainly understood as a process of assembling, but the other end of the spectrum is easily forgotten. Shouldn’t architecture in its true sense, address the entire life of a building, right from its birth to its death? It is important to acknowledge buildings as temporary agglomerations of material. They do not have infinite lifespans. Architecture comes with an expiry date, which might even be a result of cultural or societal changes, and not just the physical aspects of the building. This transient nature of architecture clearly emphasises the relation between construction and demolition. In view of this relation, it is essential that both be in a closed loop. But instead, we continue to build, use, and subsequently demolish buildings with no thought given to their ends, while continuing to build afresh. Anything new comes with a shadow of waste, and so does architecture. The effects of construction are disastrous enough, but what happens when a building becomes defunct? After the end of their useful lives, buildings get demolished, and the bulk of the waste gets carted off to landfills. The construction sector contributes to almost 23% of air pollution, 50% of landfill wastes, and 50% of climatic change (3) while the building demolition sector generates close to 530 million tons of this waste every year in India alone (4). So as architects, how do we begin to understand and recognise this?

In architecture, sustainability is not only about building methods, environmental processes, or even architectural solutions. Instead, sustainability is about the way people think and live. Hence, as an architect, our agency is not only to build and construct. Everything built must be understood as part of a larger system. A system which is conscious of every brick that enters and leaves it. Where the life of a building might end, but the existence of its constituent materials is still acknowledged. Where the role of the architect extends to understanding and visualising life as well as death of the building. Simply put, the last rites must be planned at birth, and wherever possible, organ transplants too!

A paradigm of putting into practice such an ideology becomes palpable with the example of the Chinmaya Mission Paramdham campus in Ahmedabad, a modern interpretation of a traditional and religious typology. Through our inquiry into this building, we realised that it demonstrates both, sustainable construction as well as sustainable demolition.

This system is not new and carries historical resonance. Almost 400 years ago, the Jain community built Derasars (places of worship) in the Old City of Ahmedabad. A strong religious belief, an ardent desire to cause the least amount of harm to the environment, economic viability, and hence the necessity to use the least material, resulted in the development of a building system, which exemplified the systemic possibility of scavenging, recovering, and reusing material. A part of Vaghan Pol, the Ajitnath Derasar, oldest amongst a group of five Derasars, sits clustered together, along with other traditional pol houses. Every building in this area built during that period, especially the Jain temples made of stone and timber, used this principle of construction. The building practices were part of a closed network of use and reuse and thus, the loop remained intact. The Ajitnath Derasar is archetypical of this system.

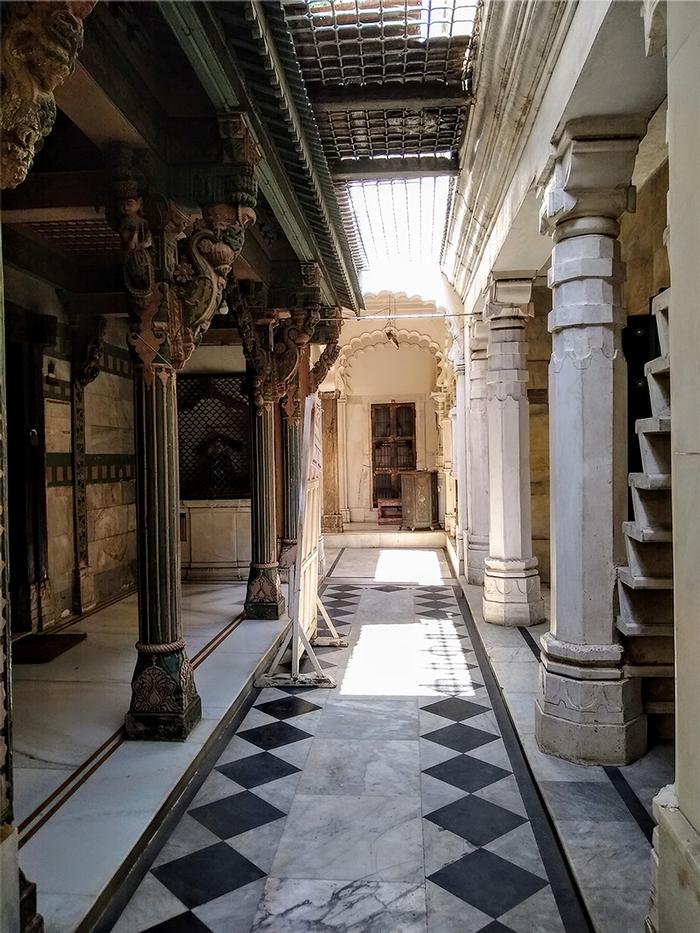

We reached the Pol on a Saturday morning, which is the prayer time for many residents of the Pol. The serene atmosphere was only broken by the sounds of prayer emanating from inside a building, that looked as nondescript and unremarkable as any wall of stone. No markers, except a grimy board in Gujarati identified the building as our destination. But as soon as we entered, it was clear why this building was exceptional. An extraordinary hybrid of sandstone, timber, and marble, each element characteristic of it’s varying age, put together in an evident montage. Barefoot on the cold marble flooring, we waited, scanning the stark contrast between the interior elaborately carved timber columns and the exterior white marble columns (Fig 1). Finally, the priest turned, and on talking to him and the people around, we inferred that the Derasar was originally built exclusively in timber. As and when time took its toll on various elements of the structure, they were carefully replaced. The stone used for later additions to the Derasar, wasn’t freshly cut either. Instead, it was reclaimed from the demolition of stone mosques from neighbouring areas. This frugality of resources by reusing was manifested in every step of the process of construction, whether it was a temple, a house, or even a community building. Individual elements could be replaced without disturbing the integrity of the system. Each element was given new life. The waste was minimal.

The Chinmaya Mission campus is a contemporary version of this idea. The Mission promotes the methods of ‘jirnoddhar,' ‘jirna’ meaning decay, and ‘uddhar’ meaning rejuvenation, even through the methods of construction. A small community, the Mission needed a new campus due to the weathered conditions of the buildings and leakage in the concrete. It had to undergo urgent renovation. They required a new temple, as well as a new building for an office and classrooms. The architects not only took responsibility of the new design, but also took charge of unbuilding the built. They bridged the unchecked gap between building and demolition, thus completing the loop.

First, they questioned the very need for demolition. Could the old temple be repaired? Was part demolition even a possibility? Due to structural reasons, instead of renovation, the old buildings were demolished to make way for the new ones. Second, the architects scrutinised the demolition process. Active efforts were made to minimise the waste and increase the yield of reusable materials. The buildings were cautiously dismantled piece by piece. Most bricks were recovered, and maximum wood from doors and windows was kept intact. Concrete was sent for recycling, the bricks sold for affordable housing, and the reinforcement steel was sent to other industries. Third, the efficiency of the material was persistently reviewed in the design process. The design of the temple shikhara, as a process intended to minimise the material usage, especially concrete which has a high embodied energy and low reusability quotient. The adequacies and inadequacies of the form, the pros and cons of assembling and maintaining the building and the composition of the material, were under constant probe.

The result of this process is the present temple and classroom complex of the Paramdham Campus. The folded plate concrete shikhara of the temple was designed to use the least amount of material (Fig 2). Constant resource consciousness and cognisance guided the replacement of sand with fly ash in the mix. Special bricks made by recycling old brick debris were used. The railings and the temple doors were made with salvaged wood, and the ratio of the mortar used was such that if at all, say 50 years later, Jirnoddhar was to happen, nearly all the resource could be recovered, brick by brick, and piece by piece (Fig 3).

This process was possible only with the collaboration and expertise of agencies beyond that of an architect. Natubhai’s demolition business was one of them. Today, few individuals are involved in this, and even fewer in the business of salvaging and reusing. Natubhai, a veteran in this field, has been handling his demolition business for the last 32 years. He specifically refers to the demolition waste as ‘civil damage,' citing the high costs of collecting this waste. Due to the nature of this construction and demolition waste, it can only be picked up at night, usually in the wee hours of the morning, as they don’t have the permission to operate during the day. Talking about the returns of RCC civil damage, Natubhai calls it utter waste since it is very difficult to reuse, unless specified on site as aggregate for the new concrete. But steel on the other hand, has a very high resale value, being recycled easily. Even ‘sariya’ the reinforcement steel is reclaimed, while some of the demolition steel is sent to other industries and recycled to make new products like metal buckets. As for bricks, the resale value is quite low. Newer brick construction uses very low-quality bricks which are almost never reused. They usually get carted off to landfills or to level low-lying areas. Sometimes these bricks are even used for temporary construction, to house the labourers on site, or are sold at very low prices, almost half the market rate, for constructing low income housing. “Grahak nahi maante,” clients don’t understand the use of these second-hand bricks, he says. Kota stone, used as flooring, too has a time consuming salvaging process. Because of expensive labour costs of dismantling, this stone instead of being reused, is thrown away, unless directed otherwise.

Similarly, Kesarjan, a brick making business, run by Keyurbhai is one of the very few establishments that recycles demolition waste (Fig 4). They are committed to the principle of using waste as an ideal raw material, majorly brick debris and fly ash, compressed and stabilised with lime. Using nearly seventeen parts of crushed brick debris for every five parts of lime, these bricks are highly eco-friendly and efficient. Keyurbhai is particularly proud that the firm purchases the debris, since it adds value to what is otherwise considered waste, and hence, creates a constructive contribution to the economy. Only due to the recent increase in awareness to use recycled materials, his business has flourished.

From these examples, what is unmistakable here, is the importance of commitment and understanding on part of the architect as well as the client. Architects find it too taxing to specify these extra measures of reuse and recycle, while nobody understands the gravity of the issue. Cultural associations, societal pressures, and sometimes sheer laziness builds up the constant demand to use virgin materials. These hindrances call for alternate approaches to promote the systemic possibility of reuse and regeneration. The change needs to occur at the very root of the system. We imagine the process of construction as a complex system of interdependency and associations which involves a step by step structure of evaluation and modification in the existing system. A systemic possibility of initiating a transformation in the way we design and build.

This is not only applicable to the professional network, but social engagement is important as well. Since the architects of Chinmaya Mission were designing a replacement for an establishment which was of extreme importance to a community, they experienced negotiations with and expressions of contradictions from various agencies. Some were a part of the community, while some were not. Architecture did not remain the prima-donna in this multi-centric decision-making process. Instead, it weaved the community together. It also understood the intangible aspects of design. Reminiscing the night before the demolition, the architects remember the old temple lit with diyas (oil lamps) as almost the entire community came to bid their goodbye to the structure which held exceptional sacred importance. The sight, they say, was symbolic of the significance a space holds for a community. Care diminishes when emotional anchors are removed. Hence, it was important to have the community onboard with these unconventional design choices. Through participatory methods and regular deliberations with the community, the designers made sure that this sense of belonging was to continue.

Through the means of such a holistic design process, the architects became the proponents of a system of construction, perfectly complete in its manifestation. The system which looks at architecture as one of the many agencies which come together in the building process. Where, the architects extend their role from designers to that of influencers of society by providing solutions.

Imagine if every client agreed to a slow and conscious process of building. Imagine if the state subsidised and promoted the innovation, manufacturing and the use of recycled building materials. Imagine if there were incentives awarded for dismantling buildings instead of demolition. Then every designer would adopt and embed the idea of retrieval and recovery during conceptualisation of the design. Every architect, instead of building anew, would choose to reuse and recycle the existing building and materials. And every builder would carefully evaluate the efficiency of structure and deliberate on material usage before construction.

This process of parts would then become a systemic possibility. A loop, that is inclusive of all the stakeholders which affect and get affected by this sector of designing, building, and demolishing. The architect’s initiative impacts and extends to the society at large, in more ways than one. The influence such a design has, is wide ranging. An architect’s decision making directly affects the client and the user. The more the architect employs the system, and firmly incorporates these ideas of minimal usage and reclamation, the more the community and the public, trusts the possibility and credibility of such a system.

This system can adapt itself across a multitude of methods, materials, and ways of building. It requires contribution, by the architects who design the building, researchers who innovate technology and materials, manufacturers who produce and fabricate materials, and all the other participants, who are the links of a closed cycle, and are equally invested in this strategy of resilience. This approach not only has the capacity to recover from the difficulties of today, but is also flexible enough to attune itself to the unforeseen hardships of the future. It’s a system of equity of sharing responsibility. And when every collaborator takes onus of their respective responsibility, the system cannot be shaken.

The system is inclusive. The system is resilient. The system becomes the way of living.

References :

1. M. B., & J. D. (n.d.). Regeneration and Recovery. Retrieved from http://www.plea2014.in/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Paper_3D_2353_PR.pdf

2. William McDonough, and Michael Braungart. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002.

3. “How Does Construction Impact the Environment?” Initiafy, 23 Aug. 2018, www.initiafy.com/blog/how-does-construction-impact-the-environment/.

4. A. S. (n.d.). Solid wealth. Retrieved from https://www.downtoearth.org.in/coverage/urbanisation/solid-wealth-45805

5. Till, J. (2013). Architecture depends. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

6. Sassi, P. (2015). Strategies for sustainable architecture. Routledge.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |