[ID:3191] WESTERN INDIA : AT THE CROSSROADS BETWEEN TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE AND CLIMATE CHANGEIndia “The Earth provides enough to satisfy every man’s needs, but not every man’s greed.” - Mahatma Gandhi Humankind since its inception has demonstrated the excellent capability to adapt to their natural environment as well as self-imposed challenges. In all the crisis, they have turned towards nature for the solutions. However, modern civilization has outgrown the capacity of nature, leading to a shortage of resource and unpredictable climatic behavior. The new problems have led to the shift in paradigm, with Urban Design and Architecture now focussed towards efficient resource management, infrastructure planning and designing for climate resiliency. This has become the need if human civilization wishes to adapt to the changing climate of Earth, and preserving it for future generations.

In this scenario, we look back to our ancestors who have developed ingenious ways of modifying the surrounding to their advantage and established the timeless knowledge systems to ensure continued survival.

LESSONS FROM THE PAST

Shimmering like a mirage amidst the golden sands of Thar Desert, on a hilly outcrop of Aravali range, emerging from the azure sky, is the Golden city of Jaisalmer; the home to the Bhatti Rajputs of Western India and the only living fort city of India. Strategically located; the desert and the hillock provided much-needed defense, the gold-laden caravans traveling the Silk route brought immense wealth, and the availability of subsurface water indicated that life could be sustained. The harsh arid climate with temperature ranging between degrees 50C and 5C, coupled with frequent sandstorms and limited availability of water (annual rainfall of 209mm) provided them with an opportunity to adopt a lifestyle based on the conservation and find ways to adapt to the climatic challenges.

“It is not the strongest that survives, but the one most responsive to change” - Darwin, Theory of Adaptation

This is clearly exemplified by the fact that the traditional knowledge systems of Jaisalmer have ensured human survival over the last 850 years, and will continue to do so, only if we adopt the principles inherent in them.

Human adaptation to Jaisalmer is clearly manifested in the methods of their appropriation of the environment. Thorough understanding of the natural cycles of the Sun, Moon, and Monsoon in conjecture with the knowledge of geography and topography facilitated the construction of elaborately planned water and drainage systems to sustain this desert settlement. Ghadisar Lake which provides water to the entire settlement of Jaisalmer sits on the limestone bed that serves a dual purpose; it ensures that water doesn’t percolate deep inside the surface, and remains fit for human consumption. The overflow from Ghadisar Lake is collected into the Amarsagar Lake located further downstream, which is a source of water for 6-8 months. The further overflow is collected into 7 'beris' (a variation of wells having a narrow covered mouth which prevents water loss through evaporation), which supplies the water for the remaining part of the year. It is interesting to note that the Ghadisar Lake alone is capable of sustaining Jaisalmer through a drought condition for 5 years.

While the collection of water was important for the survival of society, keeping the water away from substructure was equally important for the fort to sustain. The 'ghut nali' system drains the water on all four sides, has been used extensively to keep the rainwater at bay. These begin at the major 'chowks' (plazas) and run parallel to the streets, till they finally empty into the Lake at the foothill of the fort.

“The ingenious planning of Jaisalmer lies in the fact that not even a single drop of water is left to waste.”

Nowhere can the relationship between city planning and building design be clearly observed than at Jaisalmer, justifying that

“A standalone building cannot ensure survival if the environment in which it exists doesn’t function well.”

The compact layout of the town enclosed within the 5-6m high, doubly fortified sandstone walls and bastions act as a first defense against the sand storm, reducing the sand entering the fortified city. The uneven height of the built fabric is the second defense, acting as a wind-break against sandstorms. The WNW-ESE orientation of major streets and the building heights ranging from twice to four times the width of the road ensures that the facades of buildings are mutually shaded while the elements such as wind pavilion and high parapets on the terrace enable partial shading of the roof as well as the adjacent building.

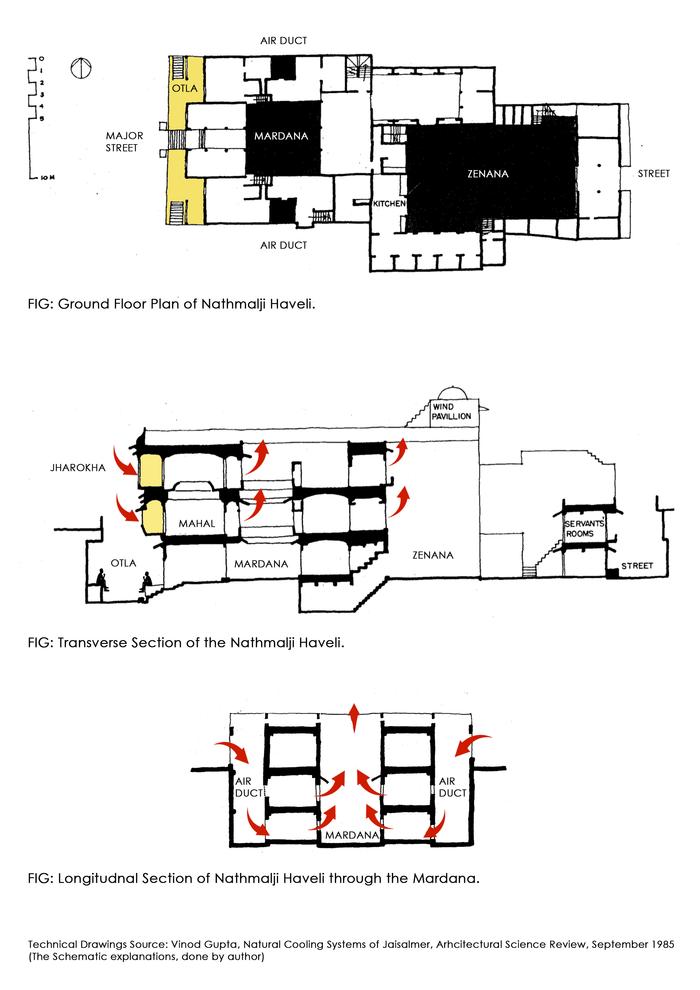

“Nathmalji Haveli” a Traditional Jaisalmer House, skillfully blends the willingness and ability of users, to organize their activities in space and time, such that not all the spaces need to be maintained at equal levels of comfort all the time. This is made possible using the courtyard centric layout which gives this haveli the flexibility in organizing functions based on climate as well as catering to the social needs. The smaller courtyard at the entrance which follows the ratio of 1:4 (Width to height) functions as the 'mardana' (male quarters), becomes the central activity space during hot summer months. The rear courtyard follows the ratio 1:2, functions as a 'zenana' (female quarters) and acts as a spillover space for performing daily household chores. The Haveli sits on a 1m high Plinth, and the walls on the lower storey devoid of any large openings, safeguard the interior from dust as well as ensure the privacy. The 'otla'(porch) forms a buffer space between the street and the entrance to the house. This space also functions as the place of social interaction between neighbors.

The first floor immediately above the entrance is the 'mahal', often the grandest and multifunctional room of the haveli. This room is used by the males of the house to conduct business and during the evening would be used to entertain guests for dinners. At the front of the mahal, overlooking the street is a 'jharokha' (a semi-enclosed balcony) ornamented with 50mm thick intricate 'jali' (latticework). The design of Jharokha is an expression of the wealth of the household and cleverly uses the principles of science to allow light and breeze as well as providing an ideal place for relaxing and allowing discrete participation of the women with the outside world. The limestone jali has a wider opening on the outside which narrows towards the inside. This mechanism helps cool the air entering the building and prevents dust.

Ram Avatar Agarawala, in his book “History, Art, and Architecture of Jaisalmer” beautifully captures the importance of a Jharokha in a 'Marwari' (local dialect). “Galiyo sir gaddal bichhe, Amal bate apraman. Mahal changi drav mansa, Samajhtiya Jaisani. “

Translated as: In the projected balconies bedrolls are spread, One can share opium without discrimination. Prosperous people live in beautiful houses, Such is the city of Jaisalmer with beauty and taste.

The walls of the haveli are made of Light Yellow sandstone, 450 mm or more in thickness and constructed of dressed stones held together by stone keys cut into the blocks or by iron clamps. The thickness of the walls was effective in minimizing the rate of heat exchange between the inside and the outside, thus keeping the interiors cool during summers and warm during winters. In the peak summer when the solar altitude angle ranges between 54 and 86 degrees, even a small horizontal projection is sufficient to shade the Southern façade of the building, this is done using ornamentation on the wall surface.

CONTEMPORARY MANIFESTATIONS OF THE TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE SYSTEM

In a similar environment, with the need to sustain 7500 people, the designers of National Institute of Information Technology (NIIT) University, Neemrana turned towards the traditional knowledge systems of Jaisalmer.

Strategically situated along the Delhi – Jaipur Highway, the campus connects two major cities of North and West India. The site sits on a deeply eroded barren land on the foothills of the Aravali range, but owing to the harsh weather and overexploited water table, suffers from an acute shortage of water. Just like Jaisalmer, the area is characterized by dusty winds and temperatures soaring up to 45 degrees C.

The design of the University in such an adverse environment is an attempt to explore the possibility of building a sustainable campus and efficient usage of scarce resources.

As climatic theory suggests, evaporative cooling is the most effective strategy for designing in an arid climate; but one needs to think beyond it. In a place where water is a limited resource,

“Where does the water come from and how do we utilize it judiciously?"

The solution to this challenge also found its answer in the water systems of Jaisalmer. The site, like Jaisalmer, sits on the shallow hard substratum which presents a perfect condition to collect and store the surface runoffs from the adjoining Aravali Hills. Conveyance channels flanked by native vegetation on both sides drain into the detention basin created by erecting bunds (small check dams). While detention basin ensures recharging of groundwater, it also allows particles, the time to settle. This combined with native vegetation ensures that the eroded particles do not enter the basin and also prevents against loss of water through evaporation. To manage the resource well and use not more than the annual discharge for consumption, practices such as usage of grey water in toilets and water saving fixtures have been incorporated.

The compact planning of the site and E-W orientation of the major roads is a conscious decision against the harsh climate. Additionally, it ensures efficient utilization of infrastructural resources and forms the basis of introducing the modern concept of walkability within the site planning. The overall development of the site started with the construction of academic block (the nucleus of the design) and expanded gradually according to the needs, without disturbing the existing landscape, thereby reducing the cost of construction. The organization of functions in keeping with existing site topography utilizes the heavily contoured site for outdoor spaces like the amphitheatre and the sports arena, whereas the buildings occupy relatively flat terrain which effectively minimized the cut and fill process. The pedestrian spine connecting major residential and academic areas follows the width to height ratio of 1:4. This further helps in creating shaded spaces that are used for social activities.

The design of traditional open spaces such as chowks and courtyards, which dictate the lifestyle of people has been used to organize the built and the unbuilt fabric of the Campus. Tight packing of the buildings allows channelizing of winds, coupled with the evapotranspiration through the vegetation, cools the open spaces and makes them a vibrant student activity area.

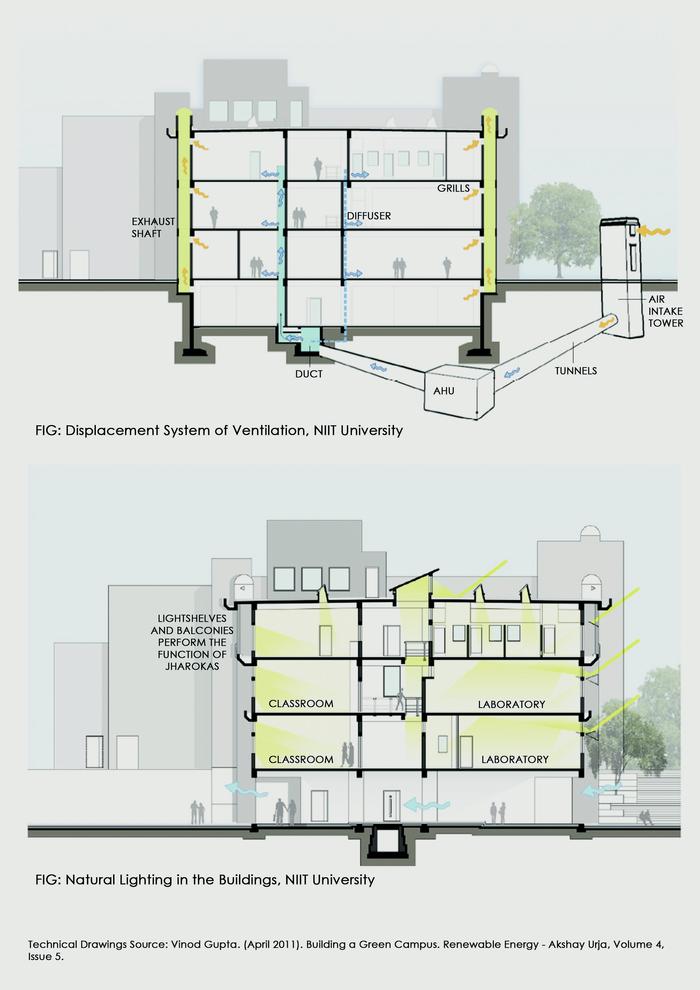

The traditional know-how of minimizing heat gain found its contemporary solutions in the usage of a 50mm thick vermiculite plaster on the West and south façade. The projections in the form of light shelves and balconies provide shade to the recessed glass windows, which parallels the function of the Jharokha. Classrooms which require uniformly distributed diffused light are placed towards the north, while the laboratories that require dry and sterile environment are kept on the south side. The windows placed on higher levels and shaded through light shelves facilitate uniform distribution of the light inside these spaces. The spatial organization of the University again finds its genesis in Jaisalmer;

“Not all spaces have to be maintained at equal comfort levels at all times.”

Mr. Kamal Singh, Head of the University’s Project Management Team talks about the use of an economical and sustainable way of cooling the building that uses earth as a heat sink and earth air tunnels to pre-cool the air before supplying it to all the parts of the building. Towers placed at several locations on the site, captures and directs the air into the tunnel, about 4m below ground (where the temperature remains constant at 24 Degrees Celsius). The heat exchange with earth brings the air temperature down by 12 Degrees in the summer and heat it in winter. The air is later humidified or dehumidified as required and supplied through L shaped ducts. To make the system more effective, the displacement system for ventilation is used which displaces warm air through the ventilation chimneys placed at higher levels as cool air at 20 degree Celsius enters the room at the floor level (Stack Effect). This system has played an important role in significantly reducing the energy consumption of the building while providing 100% fresh air. The design of Neemrana affirms the relevance of Traditional Knowledge systems even in present scenario and help designers see traditional architecture not simply as a historic style but as a knowledge system too.

JAISALMER: TIMELESS SURVIVAL

Built impregnable and meant for sustaining 15,000 people, the Jaisalmer fort now stands vulnerable from overpopulation and modern technology. As it silently cries for help, its pleas are subdued under the want for modern comforts by its own residents. The new water systems installed in the city has undoubtedly made life easier, but the seepage from it has also brought problems along with it. The walls of the fort are crumbling slowly under the reckless and rapid technological interventions.

“The oak fought the wind and was broken, the willow bent when it must and survived” - Robert Jordan, The Fires of Heaven

A similar level of resiliency is demonstrated by Jaisalmer, which has always understood the need, ensuring that the settlement not only survived but thrived. This perfect summaries, that the need for resiliency cannot be simply achieved by modern interventions alone, but supplementing it with the Traditional Knowledge systems.

Amar Singh, a shopkeeper, remembers the days when women of the household would walk down the narrow roads carrying golden pots on their head. He also recalls, sweeping of the streets, unclogging of drains and cleaning of the wells by the residents; the celebration that began a few days before the onset of rains.

As we finish our conversation with Mr. Singh, his eyes glee up with hope at the sight of the distant grey clouds. The glee soon turns into a wide smile as the first drop of water touches the parched soil. And thus the life in Jaisalmer begins.

References: AGARAWALA, R. A. (1979). History, Art and Architecture of Jaisalmer. Delhi. Vinod Gupta (1985). Natural Cooling Systems of Jaisalmer, Delhi UNESCO (June 1987). The Survival: Life in Extreme Conditions Vinod Gupta. Towards Building a Sustainable University Campus Gupta, V. (April 2011). Building a Green Campus. Renewable Energy - Akshay Urja, Volume 4, Issue 5.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |