[ID:2795] The Art of the Labyrinth of Being & Not-beingBangladesh Just a few million years ago, the vast Bay of Bengal left a little space to welcome a lovely little delta, the daughter of the Himalayan rivers. This little delta is Bangladesh and this selfless art of welcoming is inherent in her spirit, culture and traditions for thousands of years. The society I am speaking of has recently created an incredible example for all the societies out there. Bangladesh has become the home for more than 0.6 million of homeless Rohingyas seeking protection from their own society. Eventually in 1971, India also gave shelter to millions of Bangalees. Regardless of political boundaries this whole sub continent is threaded in a string of conviviality. This spirit of conviviality is comprehended in every aspect of our society.....even in architecture, not the intricately designed but the simplest one. I intend to tell the story of Dhaka, particularly its people and how the simple attributes of architecture...a nonfunctional culvert and extensions of plinth or hanging balconies are comprehending our social spirit , being part of our social engagement even not being designed to be so.

To understand the impact of architecture in a society, the context of the society is needed to be concerned. Dhaka, a city of heterogeneity, lies on the geographic co ordinates 23.81° N 90.41° E. Dhaka is surrounded by the rivers Buriganga to the south, Turag to the west, Balu to the east and Tongi khat to the north. The city once was imagined to be the ‘Venice of Bengal’, a city on water! But in reality of a third world mega city, there is indeed a brutal mismatch between dreams and demands. Its lush green aqueous landscape lost its sophistication to the concrete urbanization and tidal flow of population. The once city of 'Dhak' (Butea frondosa), Dhaka is now the city of 18 million hearts beating as fast as the trails of urbanization. With an area of just 325 square kilo meters and a density of 23234 people in per square kilo meters, it has ranked as the 4th most populated city in the world. Its ranking as the 4th least livable city in the economist's list vindicates one wise quote of Charles Correa, "Everyday it gets worse and worse as physical environment....... and yet better and better as city." Still Dhaka is one of the rapidly developing ‘happy’ countries in the world on socio-economic premises. These ambivalent data leave a big question unanswered......how this society is revived and what makes this city of deficiency a city of conviviality and happiness? With our paradoxical reality seeking an answer to this question is quite implausible, not impossible! It even leads us to the deeper understanding of simple attributes of our architecture.

"Architecture is the art of how to waste space." - Philip Johnson. With an acute scarcity of housing land, here is no space to waste on society in Dhaka yet like the rise of the delta itself on the edge of Bay of Bengal, a little space was left in front of the houses in old Dhaka. In this geographically low lying delta, Dhaka is surrounded by rivers and its monthly precipitation is recorded to be 156.3 mm. Thus the houses are built on 457 mm high plinth. In old town, houses are built with an extension of plinth and a courtyard amidst the house. Though the courtyard is the most significant feature, the extension of plinth has even greater significance. In modern architecture the extension or ‘Rock’ or the inclined balcony can be referred as the foyer or porch. Houses were being built this way since Mughals built the city 400 years ago. Today still we find some traces of such buildings but the traces left on the society than in actual form is even more astonishing.

Houses in new town are not as of in old town. Here are no semi shaded balconies in front of the houses. People make high boundaries that are so protected that nothing can get beyond them, neither invaders nor values.....People hardly get to know each other here. All of these create a significant difference between societies with and without those rocks.

Rafiq Azam , a renowned architect of Bangladesh, talks about the impact of the hanging balconies on the society and its people. Growing up in Lalbagh in old town, he has been a part of a celebration throughout his childhood….celebration of life, of humanity. In his nostalgia of childhood, he speaks of not having a single house on an alley but the whole alley being his home. He had known everyone in that neighbourhood. Everyone was related to everyone. In his memories, there were not many families living in harmony in an alley but a single family with a lot of members living in a house of several partition walls and the street as their long open to sky courtyard! By growing up in that neighbourhood, the architect has found the true spirit of our society in those simplest of architecture and has been able to design equally successful designs in the new town.

The architects' experience links back to the traces of our heritage. My search for the traces of that heritage led me to the streets of old town but the search wasn't as easy as it seemed to be. The first place I went was 'Goltalab', a recreational space. But all I could see was a bounded pond, a guard in the gate of the boundary and several notices on board about rules and entry fees. People who paid would go on the other side of the boundary and others would just peep through the railings. Even though I had not studied much about the social art of architecture, I knew that a set up for society could be anything but this. Again I started walking through several markets, walked in a huge crowd but none seemed to bother. I was desperately looking for the air of conviviality in the urban smoke.

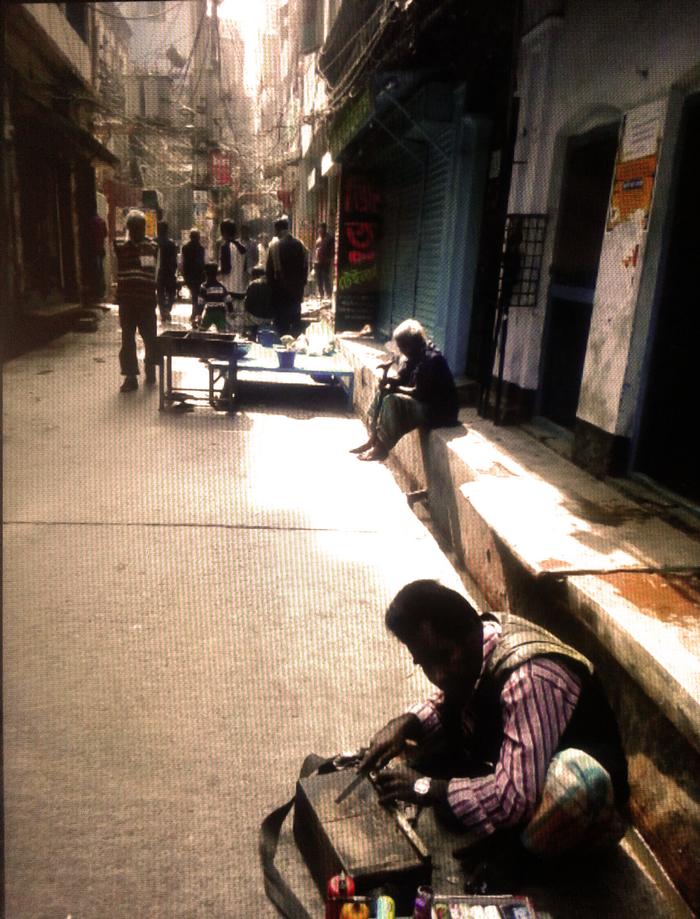

My search ended coming to an alley of Shakhari Bazar. The roads of old town are generally 2 to 3 meters. It gets narrower here. Here are rows of old buildings on both side of the street regardless of all architectural or ergonomic requirements. But the houses have the same features of our age old heritage. They have courtyard amidst the house and that very semi shaded balcony or just an extension of plinth. As soon as I stepped in that alley, I felt relieved. It was the same people, the same street and same crowd but not the same environment. There were confectionery shops on the edge of the road but no boundary. There were trails of run down extended plinths of several houses adjoined together. Tired of all the grey chaos, I sat on one of the plinths and just suddenly I became a part of that neighbourhood. I felt like belonging to the crowd. I could now talk to anyone on that street. I could stand for hours inside any shop and click photos of other side of the street. The street further got narrower but I didn't mind walking along the crowd. Though the people didn't invite me in, I knew I wasn't uninvited. I knew that I belong here. These are people of my society. We have the same roots and similar view of life. Though I didn't know anyone from there, everyone I talked gave me a wide bright smile instead of big staring eyes as the guard on the pond or the men from the markets.

Different from a rude, suspecting neighbourhood, they have established a very warm and beautiful language of friendship and trust through a simple aspect of architecture. The plinths are the part of particular houses yet belong to the whole society. They are like an interface between the home and street connecting individuals to the whole of society. The dwellers of the houses don't bother about building high boundaries for protection or privacy. They are not afraid of being invaded by the strangers. They don't drive away strangers rather welcome them with a warm smile. Eventually they put a pitcher of water for the passersby to quench their thirst of both water and affection. Here the monotonous grey canvas of the city gets coloured with numerous shades of smile, shades of life.

In my return journey from old town to new town, the more I was getting to the north, closer to my home, the more that image was fading away. It was gradually losing its shades and till the moment I reached my destination, that image of numerous shades was turned into a complete monotonous grey. Here are fewer people on road, a lot less chaos, a lot more clean and a lot of coloured high buildings challenging each other’s existence but mostly here are a lot more boundaries. Here are boundaries between houses and street, between hearts! And these visible invisible boundaries are one of the main fall outs of our civilization process. Though population density is lower in new town than old town, the emergence of boundaries and segregation of least privileged ones from the most privileged ones have worsen the scene.

Among all other aspects of new town, poverty is the most prominent and distinct. Referring to this Charles Correa had written in his essay “Space as a Resource”, “This urban poverty is perhaps the worst pollution of all”. All the 4500 slums of new town are the traces of this poverty. Being a resident of Mohammadpur in new town has given me a privilege to witness the demise and reincarnation of one of those slum societies of Dhaka. As the cruelest toll to the development, a low earning housing space has turned into a slum over two decades, the only school was broken to make space for more people a decade ago. This community is deprived of their right of privacy, drinking water and sanitation. Their children have lost their play field! This people have gotten poorer but not ‘dehumanized’. They are deprived of most other happy aspects of life just like the other slum dwellers out there but with a simple privilege…a 30’x46’ culvert, a platform to celebrate their existence and cherish their humanity.

This slum is separated from the superior society by a streak of black water. As a token of development a culvert was built just a few years ago over a stagnant lake. By the time culvert has become an inevitable element for creating numerous happy memories for these people. . In this concrete city of injustice and imperfection these people have somehow found their own agora, a hub of life, in the form of this culvert. As an exception to other numerous culverts built in this city, this isn't a path only. It has a great aspect and even greater impact.

In this east-west elongated culvert, there are three permanent tea-stalls, on the west edge, northeast corner and southeast corner (image 3). Everyday people of this slum can have a fresh start of their day with a cup of tea. In the time of world cup Cricket a huge crowd gathers in front of the stalls to enjoy the match. A traditional Bengali cake vendor sits beside the tea stall on the south edge. He has been sitting here in morning and evening for last one year. Some day labourers park their rickshaws and vans on the south edge daily. A 'Jhalmuri' (puffed rice) seller often sits in the southwest corner (image 4) and kids and young men gather around him. Slum people celebrate their new year, independence day, victory day, wedding everything right here.. All the slum children play here, sometimes by dragging each other with a small cart or sometimes flying kites. Old people bask in the winter sun sitting on the edge. New parents of the slum come here for a walk with their little child to cherish their birth right of oxygen. The culvert is always filled with people sitting and talking in the tea stalls or just on the edges of the culvert. They talk about life and possibilities. These people live in harmony. Unlike most other slums out there, they have less criminal records. They are not addicted to drug but to this privilege. Their children are not child labourer. They go to school, they play, they dream!

"Thus far from being an indicator of the demise of people, they are sign of hope, of the will to survive"- this quote of Charles Correa from the essay "Urbanization" about these squatted society begets a question….what works as a catalyst in this process of revival of a squatted community? Here in new town, the culvert is the ultimate answer. The culvert has given them a platform to dream, a platform of hope! Regardless of dirt and pollutions, all of them together see a dream, a dream of neither money nor privileges but possibilities and happiness. Here the monotonous grey image of new town regains its shades.

These slum people have loved the culvert and it has loved them back and so in the old town. Those extensions of plinths have given them courage to love the strangers and strangers also love them back. Van Gogh had once written, "I feel that there is nothing more truly artistic than to love people." While looking for the answer to the question of 'social art of architecture', several layers of my society has been unfolded to me. I realized architecture is not only about ergonomics, building code or spaces, it's more than that. It’s about people, people who live surrounding it, people who cherish and celebrate its existence. These people again belong to a society bounded by social engagement. This social engagement is an aesthetic in itself. Those little attributes of architecture in my society have embraced that aesthetic. They beget joy and optimism. They have become the poetry of life of the people surrounding them. They have indeed become pieces of social art. Regardless of being in different edges of the city, they are threaded together with conviviality. But they were not designed to be so. This whole city of Dhaka is a city of paradox. This small attributes of architecture are present and absent here in the same time. This city is like a labyrinth of being and not being. After getting lost in this labyrinth, I explored the true spirit of my society beholden in those simplest of architecture.

In the end….a society never revives on statistical numbers. It needs deeper understanding of the catalysts working behind this process whether physical or metaphysical, designed or undersigned. Thus the emergence of reclamation of the simple yet significant features of architecture can't be ignored. Again we need to seek small steps to make greater difference. Designing a simple public plaza or a loitering space and replacing boundaries with balconies or public seating can't change all the negative statistics into positive but the process of the demise of a society with the spirit of conviviality can surely be reversed.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |