[ID:2701] The Concurrence of AnomaliesIndia “You can’t breathe anymore. You’re looking at all the people around you, trying to figure out how they haven’t run out of breath yet; because you stopped inhaling a while ago, you’re just a heaving mess now.”

Bhopal is a slow-paced, expansive city in the central state of Madhya Pradesh, one with laid-back people and long seamless roads. But on entering Itwara, a rundown downtown market in Old Bhopal, one sees the crowd first and the street second. The traffic of cars, auto rickshaws, people all merging into one huge chaos describes a typical evening in the overcrowded colonies of Itwara.

The constant chatter of fruit sellers, repair men and meek old women selling bangles is overshadowed by habitués bargaining with the sellers on the top of their voices. We walk past the war zone, take a right at the end and surprisingly, the crowd declutters. A sigh of relief escapes us as we wrap our minds around the change of scene. We’ve entered the residential area of the vendor heaven. Two broad roads segregated by a wide green patch provide ample breathing space between the lane of houses on either side. A building at the end of the street, a one-storey cuboidal structure paneled with bright vivid colours stands out amidst the dull scape. We walk towards the peculiarly hued edifice only to realize we’ve reached our destination, the only public toilet catering the entirety of the public.

Usually, public toilets are cramped in corners of the roads, almost as a regulation, only built to serve a purpose. They don't however stand tall in the centre or function as markers for street splitting. But this basic single heighted rectangular block looks like it is built out of primary shaded panels specially to signify an important landmark.

As to why it stands in the middle of the road, the people speak our thoughts out loud. It is a one of a kind toilet complex. It doesn’t just comprise of male and female divisions. It holds a section for the third gender as well. Such a design is rare; as a matter of fact, non-existent in India. This is the first transgender toilet complex built in the country. Its odd placing and bright colours are devised to emphasize its existence, depicting the inclusion of a community after centuries of struggle. It may be small in size, but it stands for a cause much bigger than its extent.

Its milieu marks the beginning of acceptance. It shows that we’re not ignorant of their presence in our society, that we respect them, welcome them to move forward. Our arms have been crossed and our faces have been judgmental for long. This small gesture marks the opening of arms, the slipping of a kind smile on the faces of the once neglected.

“You have the same flesh and blood. But your organs seem out of place today. You’re wondering why you have mammary glands clubbed with a cracked voice and broad shoulders. You don’t seem to understand where you stand in the crowd today.”

We, as cissexuals, usually use public toilets in a hurry. We don't ponder over a toilet sign board stating our gender before entering it. We don't hesitate, don't worry about what people would think, say or worse do. But for a transgender, they hear a woman say she’s uncomfortable by their manly presence. They are afraid of wretched men teasing them, groping them, abusing them. Thus, the toilet complex has built a barrier between the two.

The complex has a common entrance for the cisgenders and one for the transgenders. It seems to be a blatant sign of discrimination but its basis lies in the demand of segregation from both sides of the wall. The transgenders feel more comfortable in a space of their own, they like to maintain a personal bubble away from the piercing eyes. After decades of hesitance, a sudden warm welcome may come off as pretentious and forced upon. The segregation eases their normalization, sets a pace for them to merge in the crowd.

A hand has been extended but without an imposed implication to shake it.The vibrant exteriors are conspicuous but not piercing, the warmth of red and yellow is neutralized by the coolth of blue and grey. The transgender complex consists of two washbasins, a western toilet, two Indian toilets, a chamber for the disabled, a bathing area and one combined cubicle. The narrow corridor connecting the two has several posters conveying the message of transgender acceptance.

“You’re tired to your bones after the long hustle of a day you spent dancing and singing your sadness out for money. You look up at the stars and wish to lie down in the soft grass. But you’re standing at the fork in the road and the loud side is your home.”

The toilet splits the street into another narrow passage lined with vendors of all kinds on both sides. A left turn takes us to homes belonging to the people, the society forced to inhabit the side-lines.

We’re standing in an island of buildings when our pondering eyes meet Kalpana’s smiling ones. She hugs us in warm welcome and invites us to sit beside her in the veranda and all we did was enter here, no words uttered, no motives spilled. She was simply happy to see us. We ask her questions about the living conditions in her colony and more about the functioning of her household.

She explains she is a chela(disciple) and thus she cannot explain much. Our knitted eyebrows give away our confusion and so she elaborates that each of these houses have a guru(guardian) who takes in a few chelas-adopts the unclaimed or the special and provides them sufficient nutrition and protection in return for monetary help at the streets.

She had no complaints about her environment; acceptance for these narrow streets was injected in her bones at an early age. Her smiling demeanour only slips when we question her means of livelihood. She takes pride in her job and can’t comprehend why we bring up trying different professions.

We bid goodbye and walk into the street beside. Our spirits were uplifted on receiving positive greetings again. But then the tale twisted, and we turned desperate in search of escape routes. These were a different group of people. The conversation became awkward as constant teasing occurred from their side and our questions turned to mumbles and we fumbled on our words. The kind rapport we had developed was popped in these fleeting moments. Their hands of blessing soon began to caress too much of our bodies. It all seemed opportunistic and extremely inappropriate. We got out quite quickly and needless to say, quite scandalized.

We were hesitant or rather confused to write this essay for the next few days. But we realized in sometime how we too had judged the entire community based on a singular negative experience. It was wrong of us to have approached them as transgenders, as subjects of an essay and not people. Sometimes we forget that humans can both be good and bad no matter what gender, race, caste or religion they belong to.

“You take your head outside the car window, feel the wind in your hair, smell the green in the air. You’ve always loved to drive on empty roads. But this once, you can’t help but wonder if it is suffering or peace that keeps this town so silent?”

The cab speeds through the farmlands surrounding the highways, occasionally slowing to let the farmers leading the sheep and goats pass by. The scenario almost resembles our blind faith in religion. We were just dozing off when we caught this moment and began discussing how our entire questionnaire doesn’t hold the question “why”. Why can we,the citizens of a secular nation, not offer Salah(Muslim prayers) and chant Bhajans(Hindu prayers) in the same place? Why do we need to allot different days to people of different faiths to do the very same thing-pray?

As the scene changes from large green fields to crowded kutcha settlements of Dhar, our destination seems to be close. Shuttered warehouse shops and car-repair garages are lined up on the streets, huge banyan trees cast even larger silhouettes on the deserted roads. A right and a left turn later we arrive in front of a monument of antiquity.

Bhojshala, before being converted into a mosque by the Delhi Sultanate, was a temple for worshiping Goddess Saraswati. It is now a prestigious archaeological site which is shared by Hindus as well as Muslims to pay respect to their deities. At the entrance, we find a vendor selling roses at this odd hour of five in the morning. He says he resides here; he has taken refuge in the home of his God.

“You’re standing in the middle of the middle, surrounded by narrow corridors on all sides. They seem to be closing in on you. Where do you run to escape? You realize it’s time you learn to fly.”

A narrow passage opening into an expansive open to sky courtyard sets our lungs free. The cold air in the winter morning feels gushed, the stack effect seems to sweep in the winter winds.

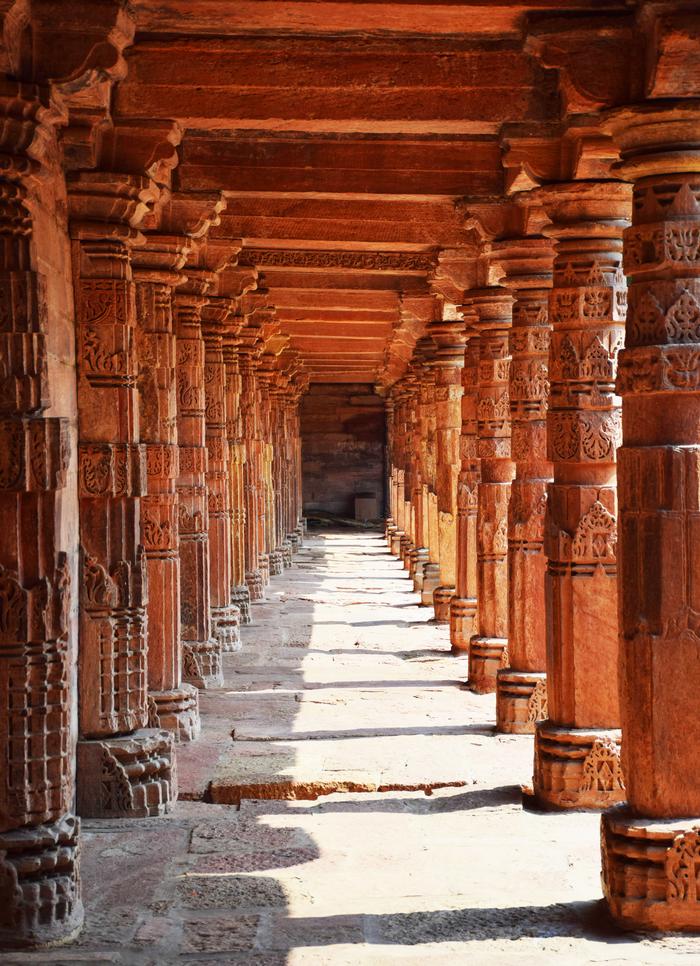

The courtyard is surrounded by colonnades on all four sides. Two of them have columns arranged on both sides forming a one-point perspective, vanishing into a stone wall with the history of its rulers embedded in it. The hypostyle parallel to the entrance is slightly wider than the other two, a minbar(part of a mosque) is built in the middle of it with a dome over its head. The amalgamation of rugged walls and flooring with finely carved columns makes it a popular tourist attraction.

At a glance, it imparts the appearance of a typical mosque but looking closely one finds Hindu scriptures and idols inscribed on the columns. A mandapa in the middle of the courtyard very much resembles the gurukul of the Hindu mythology.

Ironically, Bhojshala was neither intended to be a mosque nor a temple. It was a school, constructed in the 16th century under the rule of the renowned patron of culture and learning, Raja Bhoj. It is fashioned as modern schools are, with a veranda on four sides enclosing a courtyard, in the centre of which sits a stone platform, presumably where classes were held.

After the Ayodhya debacle-the fight between the masses of the two predominant religious groups of India over the construction of a Ram temple or Babri masjid on the historic site of importance, there was a debate of converting Bhojshala into a center for meditation and library for religious texts before it too spirals into a hurricane. How many identities does a building need to swap in order to attain acceptance by the public?

“You bow your head down in prayer, seeking a connection with the God within. But you can still hear the loud chants of the "silent" protesters. You can feel the hurt when the gates close in on them, so you could be safe within.”

There have been occasional rifts on the disputed site, primarily on days when the Hindu festival of Basant Panchami, the festival of love, falls on the day of Jum’a(Friday), an auspicious day for the Muslims. Both wished to offer their prayers, but neither wished to conjoin their blessings or even regulate them the very least.

Basant Panchami in 2006 ended up in a riot. The festival of love, this time, had turned out to be ugly. Hindus protested outside the temple all day long. Muslims were denied entry into the sacred place and weren’t allowed to spend even two hours in Salah. The day challenged India’s principle of secularism, marked a tough hour in the history of Dhar.

Eleven people were arrested, the police and military officials were crawling over the streets like vultures hunting their next target. The harmonious religious center turned into a fortress of barricades in a day.

But it wasn't all in vain. A lesson was learnt that day. The community perhaps realized that they had in fact, for the past decades, been unknowingly sharing this very place. The Muslims bowed down in prayer on the same podium where the Hindus recited their prayers. It was a battle of imposing superiority and not reason.

Seven years later, when a similar fortuity in the calendar occurred, their participation was mature, a much-needed transformation. The Hindus prayed silently outside the monument for the hours the Muslims offered their prayers and then were led to the terrace and allowed to celebrate the Goddess Saraswati with splendor in the very same place.

It wasn’t all easy, wasn’t all perfect either, but Bhojshala was successfully able to serve the purpose it was built for, teaching. It may not have produced scholars of science or literature, but it connected two vastly opposing masses on days. It taught them to preach the love they talk about in this sacred place. Bhojshala has grown with them, it has taught them to weave a net out of the rope instead of playing tug of war with it.

“You were never blatantly told about the things you weren’t allowed to say. So you spoke when people bit their tongues and swallowed their words. You were spoken to less often then, but every place you went to still seemed to have too much to say.”

Caste and gender are the two fundamental axes of social inequality in India. Our chosen places are still talked about in hushed whispers or given looks of disdain by some, but the impact they leave outdoes the cowardice of the meek minded. They cater vastly different subjects and vary vastly in size and appearance too. But they both target to break down the barriers of inequality and injustice in our minds, offer a ray of hope for a warm, humane and secular state.

We began writing this essay with a greed of expanding our knowledge of writing, spaces and of course our chosen course of study, architecture. But these places taught us more than we could ask for. Travelling with a purpose added a whole new dimension to our mind, entering colonies and crossing streets to question the locales filled us with zeal and brazenness, spending hours on places we merely passed by developed a peculiar fondness for the spaces.

The initiation of the transgender toilet taught us the importance of small gestures, the unifying spirit of Bhojshala taught us that we’re one among many and we all belong together. As future architects we hope to design likewise spaces, to construct not just awe-striking buildings but affection-inducing public arenas. After all, it's not the tall, beautiful buildings that are written down in history as architectural landmarks but the questionable, intriguing premises that bring about large movements in humanity.

“You're Basharat Mandal, the son of a Muslim mother brought up by a Hindu guardian. Identity crisis has run in your veins just as long as your blood has, but you feel hope bubbling down in the pit of your stomach. The hope of getting rid of the crisis before blood leaves your system.”

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |