[ID:2561] From Functions to ConversationsIndia It was a hazy Saturday morning in late December in Bhopal. After getting down from the college bus, and finding myself an auto to lead me to my destination, I sat back and took in the moist smell in the air, and glanced through the openings on either side. Enroute, Central Library, I was greeted by round and onion domes, by round, Mughal and cusped arches. Often I found myself staring at the little jharokas and ornamented brackets in century old houses; midst these stood vast the pink minarets of Taj-Ul Masjid watching over Old Bhopal as it's custodian. Most shops had their shutters down while few had just opened and were being religiously dusted clean by their owners. The streets were relatively empty with few men on bicycles heading to work and kids with heavy backpacks on their backs trotting to schools. Through these narrow lanes soaked in the fragrance of freshly made tea and frying fritters and the sound of the morning azaan (call for namaz), I made my way to the library.

Soon I found myself at the threshold of a heavy iron gate that lead me to a long avenue lined with lush trees on either side. On the end of the road the sight of a quaint, large building in refreshing bright red sandstone instantly captivated me. Painted white chhatris on the top seeked to provide a contrasting relief from the red and create a picturesque background for the groups of students sitting around makeshift tables in the porch.

On entering the library, the first spaces that met my eye were the entrance foyer, the computer room and the librarian’s chamber on the left and right respectively. The foyer despite being large in size, felt modest and dense owing to the quantum of students occupying the space. Whereas the computer room and the librarian’s office seem relatively old with outdated systems on their desks. Ahead of me stood an empty shelf in the fully packed wooden rack, where I kept my bag and stepped down heading to a double heighted hall. Intricate jaalis, close to the ceiling allowed the winter sun to peek playfully and light up the huge space. The creaking sound from the fans suspended from the high ceiling provided a soothing backdrop acoustic while the musty smell of books mixed with the scent of antique lumber gave the place a serene aura. Numerous enquiring eyes looked up from their books and followed me as I made my way around the hall, navigating through narrow aisles flanked by high wooden shelves on either side. Fiction, Drama, History, Botany, Chemistry, Arithmetic, Culture and Psychology appeared to be a few subjects whose books line these never ending shelves. I felt trance bound by the simplicity and the purity of the space, to be surrounded by the many things of meaning and mystery, the rich strangeness of another world.

The library opens at 11 in the morning but students start queuing by its gates around dawn, as the reading space is provided strictly on a first- come- first –serve basis. Those who fail to find a place in the hall, settle down in the porch and around the building periphery, taking refuge under the shade of many trees in the compound.

The library built in 1908 was first conceived as a museum, is a fine example of the fusion of Hindu and Muslim Architecture. Lack of maintenance, forced it to shut down during the Nawab era only to be later reused as the State Library under the supervision of Sultana Jahan Begum. At its inception, the library had about 60,000 books and manuscripts in Hindi, English, Urdu, Persian, Arabic, and Sanskrit. Five, was the number of staff members, when Dr. Vandana Sharma started presiding over the city’s biggest and oldest library. The operators were the only visitors in a heavily encroached area. Vagabonds and beggars had made its ground their home, and children organized cricket matches here on lazy afternoons. The boundary wall existed only for the namesake; and as the day passed the area turned into a parking lot. People sped past this treasure- trove of knowledge, without even pausing to give this building a second glance.

Today, the institution has over 4000 members and houses in excess of 2 lakh books under its roof. The body acts as an intellectual catalyst for socio-cultural development by providing facilities for acquiring education and information; while organizing recreational activities and providing guidance to students from professionals of various disciplines. Library members initiate collection drives and distribute clothes and stationaries to the less-fortunate kids of the nearby slum clusters. The State Education Board cooperates actively as the groups visit and engages with these underprivileged kids. Thus the library penetrates deep into the life of the community and acts as an educational hub conducting lectures, discussions, exhibitions, employment fairs and group studies.

The expanse of this library extends way beyond its walls and embraces anyone who is affiliated with it. It has established itself as a cornerstone of the community by giving people the opportunity to experience new ideas. This space has become a social production, the outcome of ideas and relationships. Here, the works of the people that are associated with it are enriched by the stories that they hear, read and live by.

It was almost dusk, the sun’s mellow rays peeped over my shoulder as I sat under one of the many trees, reading a paperback. I looked up to see groups of young students retiring for the day. Feeling weary, I gathered my things and started to wander around the compound looking for a washroom to freshen up. I was taken aback when one of the staff members informed me there isn’t one in the premises. The mere thought of the absence of a sanitary facility in a building that catered to about 350 people on a regular basis, deeply upset me. So I exit the same heavy iron gate that had once promised me hopefulness, with a melancholic feeling, searching for a public toilet nearby.

But all I found around were some overflowing garbage bins, some men urinating on walls and some people sitting out in the open with winds on their sails, hiding their faces and exposing their bases in pristine glory. On looking at this state of the streets, questions of inadequacy of sanitation in India poured down on me. The 2011 UNICEF survey revealed that 626 million people in India defecated in the open. For most Indians, the sight of people squatting by roadsides, has become a part of their daily lives. Many people consider having and using an affordable pit latrine ritually impure and polluting. Open defecation, in contrast, is seen as promoting purity and strength, particularly by men who typically decide how money is spent in a household. They prefer to go out in the open, refusing to believe in the benefits of using a toilet just like their ancestors have done for centuries. Women are the worst sufferers. According to the UNICEF report of 2006, half of the rape cases took place when women defecated in the open. Trying to squat wearing a sari, holding a jar of water to wash herself while looking out for rapists is an unimaginable task. Widespread open defecation in India is not due to relative educational deprivation, rather to its beliefs and values about purity, caste and untouchability causing people to reject affordable latrines.

It is well established that the history and continuing practice of untouchability plays an important role in explaining why India has the highest rate of open defecation. Most rural Indians associate emptying a latrine pit by hand, a work that lower castes are traditionally supposed to do. The 2015 Socio-Economic Caste Census revealed India still had 180,657 households that were dependent on manual scavenging for a living and there were over 2.6 million dry latrines in the country.

There is a notion in the Indian society that poor people deserve ‘poor’ solutions. This, combined with a theory that the cheapest is the most economic, is the heady cocktail that the deprived are forced to drink. For centuries the lower castes, have been forbidden from drinking from the same wells, worshipping at the same temples, or even wearing shoes in the presence of upper castes. Modern laws against such discrimination are rarely enforced and poverty and violence still compel them to do the nation’s dirty work. They are seldom seen clearing carcasses from roads, placentas from birthing rooms and human wastes from pits and open sewers.

Such is the life of an untouchable, they come early in the morning and sit at community chowks, hoping to get some work. Around midday, Bittu,44, is the last among them who is asked to clear a blocked septic tank in the nearby Tulsi Nagar colony. He is sloshed by this time. His eyes float with globs of yellow and his cheeks are sunken as the city’s potholes. He looks at least ten years older. His eyes are partially damaged- the result of toxic fumes from a sewer pipeline he had to enter a few years ago. The society has a name for people like Bittu: Jamadaars (manual scavengers). They work in the sewers, with excreta against their bare bodies. They stay intoxicated by sipping country liquor to prevent feeling nauseous. Bittu has worked with excreta for thirty years now. His son who works with him started as an early teen, the same age his father did.

“No innovation in the past 200 years has done more to save lives and improve health than the sanitation invention triggered by invention of the toilet.” – Sylvia Mathews Burwell

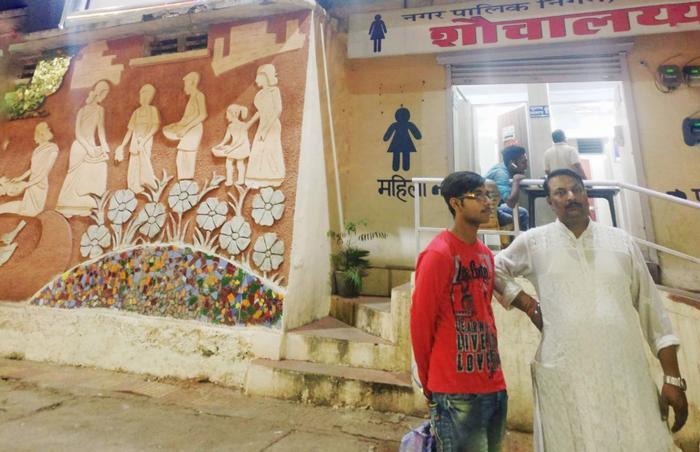

The construction of public toilets is a successful government intervention which acts as a targeted measure against inhibiting the inhumane practice of manual scavenging and the problem of sanitation. One such toilet commissioned in 2015, in the TT Nagar locality stands proudly and has evolved into a tool for social change. Located in a busy commercial setting, the public toilet complex is found at the crossroad of the market. A ramp on one side and flight of stairs on the other leads one to the complex, divided into separate sections for females and males, with respective bathing provisions. Maintained by the Sulabh International Social Service Organization, the facilities provided in this establishment are free to all.

This ‘Sulabh Shauchalaya’ is based on the two-pit pour-flush compost toilet system. There are two pits, while one is used the other is kept on standby. When the former is full, it is switched over to the other one. This slowly converts itself into a bio-fertilizer; rich in phosphorous, nitrogen and potassium acting as manure for the agricultural sector. Unlike its conventional contemporaries which use 10 liters of water per flush this model uses only 1 liter. Furthermore, this mechanism attempts to effectively eliminate the need for manual scavenging as the excreta in the pits converts itself gradually into to bio-fertilizer by the time the pit needs to be cleaned. Interestingly, this complex is not only used as a facility for people to relieve themselves but it also effectively acts a social center. Auto drivers park their autos under the shade of the huge peepal tree, seeking comfort from the harsh sun; turning the front of the complex into an auto stand. Its centrally located convenient position enables shoppers to use the facility on the go. Opportunistic road side hawkers look at this place as a hotspot for their business and are seen sitting on the front footpath making their sales. At other times, the complex provides a safe haven to waiting crowds during off hours. This toilet has gradually transformed into a local landmark, encouraging social interaction amongst the people of the area. This complex acts as a shared space whose intent extends beyond its primary functions. Such places are unlikely to be priorities, but nonetheless their effect is otherwise.

“The responsibility of architecture—indeed of any public art—is to communicate.” James Wines

The accessibility and high visibility of architecture make it the ideal medium for interacting with a large and diverse audience. It strives to link people to its physical surrounding, by creating an environment which shapes man within the natural realm, establishing a place where individuals connect with the community. Architecture uses the visual language through its built form to communicate to its users. The milieu alone cannot solely create communities, architecture spatially reveals social ideas resulting in the redefinition of a group’s identity and reorganization of their social culture. It is this versatile and accommodating nature of public spaces that make them a driving force for societal progress.

According to Stanley Abecrombie, architecture can manifest goals of social reform. Social change is not a smooth or orderly progression which evolves harmoniously; but proceeds from contradictions built into society which are ultimately the source of open conflict and radical change. A radical change in the structure of society occurs when a class is transformed from a “class in itself” to a “class for itself”. The Sulabh Shauchalaya scheme has helped liberate millions from the inhumane practice of scavenging and has provided them a second chance to a dignified life. Henceforth, architecture acts not only as a professional discipline, but also as a panacea to cure social ills in a society like ours.

Architecture is shaped by the culture of the people who create it and possesses the power to transform the patterns of their life. The architectural fraternity has the potential to bridge the gaps between the haves and the have-nots through interactive and effective design strategies. The Central library has provided opportunities to those who lack the resources and has helped them instigate a brighter future. It is a shared ground in a diverse society, a place to which whole community feels a connection with. As Architects it’s our duty to successfully induce a sense of belonging, in the hopes of encouraging relationships that will ultimately foster a sense of community.

The true function of architecture is therefore not to speak of its existence but rather to articulate mankind about their own nature. Man has been known to interact in terms of symbols. A symbol does not simply stand for an object, event or place; it defines them in a particular way and indicates a response to them. Hence the symbols ‘library’ and ‘toilet’ do not only represent a place to read and release bodily wastes respectively. But they also indicate a line of action that has been highlighted in this essay. The aim was to convey how two starkly contrasting sites in nature, form and function essentially conveyed the same ideas. Together these spaces seek to eliminate the social ills of illiteracy and untouchability in our society through their direct being and act as influential forces shaping communal development. Thoughtful design interventions like these can actually better the lives of people, if we as individuals of a developing society are willing to embrace them.

Works Cited:

Ashok Shah, G. S. (2011). Vintage Bhopal. Bhopal: Archaeology, Archives and Museum . Michael Haralambos, R. H. (1980). Sociology Themes and Perspectives. Oxford University Press. Sociology, S. I. (2013). National Conference on Sociology of Sanitation. New Delhi: Sulabh International. Madiath.J (2014). Better toilets, Better life (Video File). Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/joe_madiath_better_toilets_better_life

*Bittu is a figment of our imagination.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |