[ID:2438] ARCHITECTURE FOR THE PEOPLEUganda ARCHITECTURE FOR THE PEOPLE

Architecture to a large extent is a narration of stories as experienced by people of a particular place expressed in the built fabric. Be it the majestic and breathtaking columns or arches of Gothic cathedrals in hegemonic Europe or the rugged stick poles in rural sub-Saharan houses, either tells a specific story about people, time and place of a particular society, neither of which is inferior to the other. Most local architects in Uganda today however don’t seem to appreciate the storytelling abilities of architecture. Evidence of this lies in the ‘glass box’ buildings in Kampala, that are almost indifferent in style to those in Europe. Consequently, these buildings have, at the very least, been rejected by the environment, turning them into energy guzzlers as their occupants try to oppose nature’s wrath through acts such as air conditioning due to overheating. At their worst, these buildings have been rejected by the intended occupants for their clear luck of consideration of people’s lifestyle in the areas in which they have been erected.

In many rural settings in Uganda, it’s common practice for homeowners to informally design and construct their houses, as opposed to acquiring often rare and consequently costly services of skillful architects. Benimana (2016) of Mass Design states that the total number of architects in Africa equates to only a quarter the number of architects in Italy. To make matters worse, there are no (if any, a few) architects dedicated to working in rural areas since the few available in the country are in urban areas practicing architecture for a more financially worthy clientele. This vividly portrays the architecture profession in the country as one that is not driven by societal transformation, but rather one that aims at serving the privileged. According to the World Bank (2016), 78% of the world’s poor people live in rural areas hence making it even more pertinent for architects to ameliorate building standards particularly in these areas.

Communities are formed when a number of people share certain values/ideas that they express in many ways through the built fabric. Libeskind (2012) refers to architecture as a spiritualised art that defines what we are. Thus, this goes without saying that different communities express themselves differently (have unique identities), but this is an often understated or less considered when both government and non- government organisations propose community building projects. This in most cases results into unsuccessful architecture which the intended community does not resonate with hence does not use or even later adopts for a different purpose altogether, despite the excessive funding put into the project’s completion.

Uganda like many other developing countries in the global south relegates involvement in rural development initiatives to non-government organisations who can source required funding. Often times, developing infrastructure is one of the contributions made by non-government organisations towards combating the various problems poverty stricken rural areas of Uganda face. Sadly however, the design of most of these is anything but contextually relevant. A living testament of one of the few successful rural community centers in Uganda is the Ross Langdon Health Education Centre.

Ugandan societies, like in many other African countries are highly mythical, relating anything beyond their understanding to supernatural activities like witchcraft and evil spirits. HIV/AIDS too, in it’s earlier outbreak stages was mistaken to be a result of witchcraft in one of Uganda’s most rural areas, Rakai, where the disease was first registered in the early 1980’s. Stigma towards the infected and those that carry signs and symptoms of the scourge reached it’s peak of disintegrating the social cohesion of the community as the healthy disassociated themselves the sick.

Thereafter arose the need to inform and educate the residents towards health issues, hence the proposal by Australian architect, Ross Langdon, for a community health education centre. Unfortunately, Langdon died in the Westgate terrorist attack in Kenya on 21st September 2013, before the realisation of the project. Fortunately, however, the project was taken on, improved and later realised by Studio FH under the supervision of principal architect, Felix Holland in 2016.

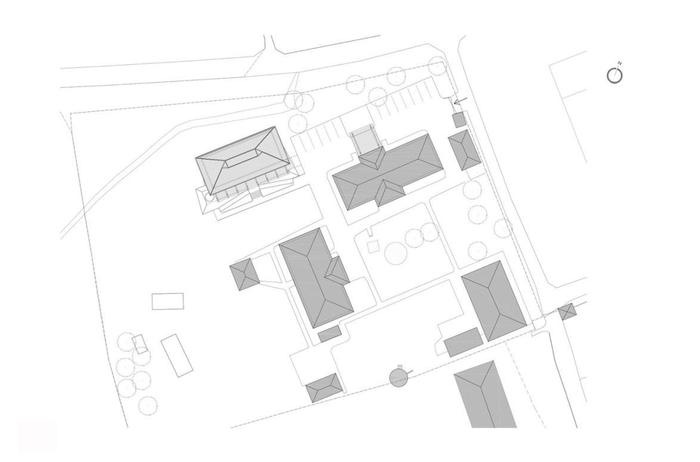

Named after the pioneer architect, the Ross Langdon Health Education Centre is located in Mannya, Rakai, a rural poverty stricken district in the South West of Uganda along the border of Tanzania. This building, commissioned by an Australian organisation, Cotton On Foundation, was intended to provide the mostly vulnerable community members with knowledge on HIV/AIDS, a disease that claimed the lives of many in the area. The approach of using architecture to counter the scourge, through proposing a health education centre, is evidence of architecture’s capabilities to transform society. Community infrastructure was envisaged as an option to foster betterment of the society by providing a common space for interaction and sharing of ideas especially on how to combat HIV/AIDS, that the community found difficult to understand. This was also necessary since the community had limited access to telephones, the internet and other popular communication platforms.

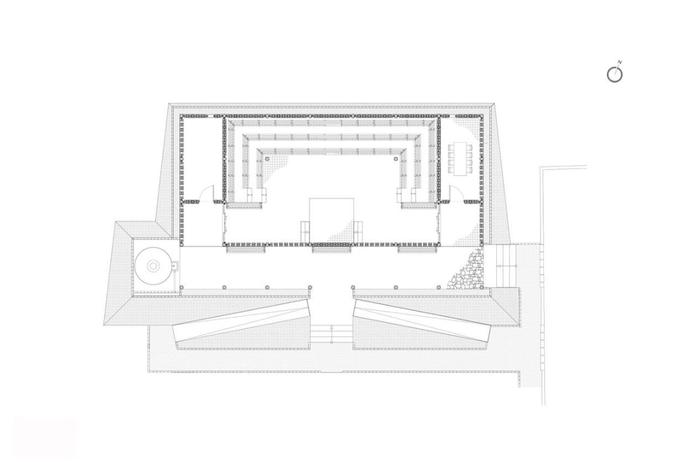

The building holds three spaces, a counselling room, a store and an auditorium between them meant for the community gatherings. Considering Ross Langdon Health Education Centre was designed to accommodate community meetings, it had to factor in the social and cultural set up of the local’s custom (Baganda culture), where sensitive matters such as the sex education talks between teenagers and their aunties or uncles are discussed in private. Due to the sensitivity of education about sexually transmitted diseases, this privacy custom was adopted through a semi- external design that has a void filled/ perforated wall. It lets in natural light and performs as a natural ventilation aid but still maintains privacy. Furthermore, privacy was explored through application of a single course of brick with voids for the northwestern façade towards the road (a public place) and more voids on the southeastern façade towards the health centre’s compound (a private place). The voids allow for views into the green landscape in the centre’s premises. Outdoor views, scenes of nature and elaborate use of colour varieties enhance healing and the feeling of wellness to the sick (Kobus et al 2008). The interplay of nature and architecture creates a serene environment for meditation and healing. Through their experience of such healing space, the role of nature as regards to one’s wellbeing and the creation of comfortable environments is illuminated to the rural community. Such deliberate design efforts allow the rural community to witness the amazing result of orienting a building with respect for nature on site. The building also imitates the semi-circular seating arrangement for the audience as commonly practiced by the Baganda.

For a rural community that cannot afford piped water and electricity from the national grid, it is imperative to explore sustainable energy and water harvesting systems. Such designs are a means to enable the community access ecofriendly ways of acquiring resources like solar energy, geothermal energy and water thus ensuring efficient and affordable day to day running of the building. The Ross Langdon Health Education Centre has a rainwater harvesting system from which water used in the facility is sourced and solar panels that ensure it has power. These systems are sustainable and affordable in the long run thus a positive contribution to the rural communities. inspire residents It is through appreciating and improving the readily available materials using appropriate technology that socially transforming and impacting architecture can be created. Thus this approach also merges the building with its context / already existing landscape. Architecture ought not to be entirely new, but rather have a connection what already exists (Allison, 2006).

The Ross Langdon Health Education Centre was constructed using materials such as clay brick and tiles, locally sourced Eucalyptus, steel, glass, locally made mats, Zinc-Al iron sheets, and transparent plastic bottles for the ‘litters of light’ which are essentially bottles filled with water letting in light through the roof. These materials were chosen not only because they were locally available in the region but also because of their cultural, environmental, economic, and structural properties. The use of eucalyptus poles as structural elements demystifies alternative construction techniques in the rural community where most load bearing elements are made from more expensive materials such as brick and mortar. Zinc-Al iron sheets as a roofing material are not only an economically logical roofing option but they also aid in the creation of a cooler interior due to their reflective abilities. Contrary to the belief that ‘silver roofing is for the poor’, using Zinc Al Sheets on such important community infrastructure can help in breaking such a derogatory chain of thought and also be a means of demonstrating the potential of this efficient material to the masses.

The use of ‘modern’ materials (such as steel and glass) in this context does not mean that the architecture loses its identity, but rather the interplay of local materials with these ‘alien’ manufactured materials is a way through which to create meaningful architecture. Architecture should fit in both the local context within which it lies but also at the same time be able to reflect the current global conditions (Frampton et al 2001).

Despite the building’s embodiment of locally available materials in their raw state, delight (which is an important aspect that draws people towards using architecture and also ensures how long it will be preserved) was achieved. It is the same delight that makes sustainable architecture attractive and worth adapting for a rural community that is poorly versed with the relevance of sustainability. Communities can be influenced towards adopting practices of sustainable architecture by showing them the aesthetic potential in environmentally friendly material choices and construction techniques.

Beauty in the Ross Langdon Health Education was achieved through the use of ‘litters of light’, coloured varieties of the clay brick and ‘mukeeka’ mats (the ceiling material). The employment of local craftsmen such as the mat makers is not only culturally symbolic but also is a source of income for the rural community. According to Frampton (2001), engaging a community in a programme is a means towards a successful project and also empowers the community to better itself.

Apart from fitting the building in its context, the baked clay bricks were adopted in this project because of their aesthetically pleasing red colour variations that weaves a unique aesthetic in the building (personal communication with Felix Holland, 11th November, 2016). The common practice in the area is to cover up the imperfections in the brick work by the local builders with plaster, wasting a lot of money due to poor craftsmanship whilst making the commonly used ‘road side’ brick that is irregular in form.

Despite the Ross Health Education Centre initially developing as a place where the community convenes to be educated about HIV/AIDS, it has developed into a multi-purpose community centre. It is currently being used for medical education, clinic- patient education for the patients, entertainment for the community through the airing of football matches, and also for farmer’s association meetings. As the community convenes for other activities unrelated to health, people get the opportunity to have health workers sensitising them for about thirty minutes before they can carry out their own meetings. People are drawn to its unique and amazing aesthetics achieved with local materials and are thereafter inspired to learn from the building’s re-interpretation of local materials.

Residents in rural communities ought to appreciate the fact that their surroundings have all the resources they need and should manage them amicably to achieve self-sustaining communities. rural areas unlike urban areas, are the best destinations for society transforming projects like these since they are constantly growing into larger Urban areas of their own. The adoption of locally available resources is also key in combatting societal underdevelopment since these make it is easy and cost efficient for the communities to repair and refurbish the buildings even after the NGOs have withdrawn from these communities. Locally based contractors being employed to construct exemplary architecture is another way of disseminating good practices to the community as well as boosting their rural economy. They can also be taught and given better means to perform their craft during the construction process thus indirectly impacting the community.

It all comes down to equipping communities with the necessary knowledge to enable them better evaluate their decisions. If architects in rural areas make an effort to understand and develop the available local materials and construction techniques, and most importantly, involve the local community in this process, community transformation will then be possible. Schools of architecture too, need to educate built environment professionals to be more open minded and to take pride in the heritage of this country and the materials and opportunities that our context has offer. This can be achieved by questioning how we build and who builds if we are to transform rural communities all over the world.

References

Allison, P. (ed.) (2006), David Adjaye Making Public Buildings, London: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

Benimana, C. (2016) Architecture That Serves the Community, Design Indaba, Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=033UAUihI6w (Accessed 3rd December 2016).

Frampton, K., Correa, C. & Robson, D. (2001), Modernity and Community: Architecture in the Islamic World, London: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

Kobus, R., Skaggs, R., Borrow, M., Thomas, J., Payette, T. & Chin, S. (2008), Building Type Basics for Healthcare Facilities, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Libeskind, D. (2012), Architecture is a language. TEDxDublin. Available at: http://www.Youtube/watch?v=yEkDosanxGk (Accessed 05 October 2015).

Ross Langdon Health Education Centre’s architectural details; Dialogue with the Principal Architect at Studio FH, Felix Holland, 2016.

Ross Langdon Health Education Centre’s performance details; Dialogue with the In-charge/Clinical Officer, Vincent Kyeswa, 2016.

World Bank (2016), Annual report 2016. Available at: http://www.worldbank.org/en/about/annual-report (Accessed 23rd November 2016).

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |