[ID:1614] Rumah in the Woods : Resurrection of the Nanga Sumpa LonghouseIndia “These bodies are perishable, but the dwellers in these are indestructible and impenetrable.”

This verse from Bhagavad Gita (a Hindu religious scripture) speaks about the human body and soul. For me, even a piece of architecture has a soul which rests in its place. We can feel its presence even when the building is no longer there.

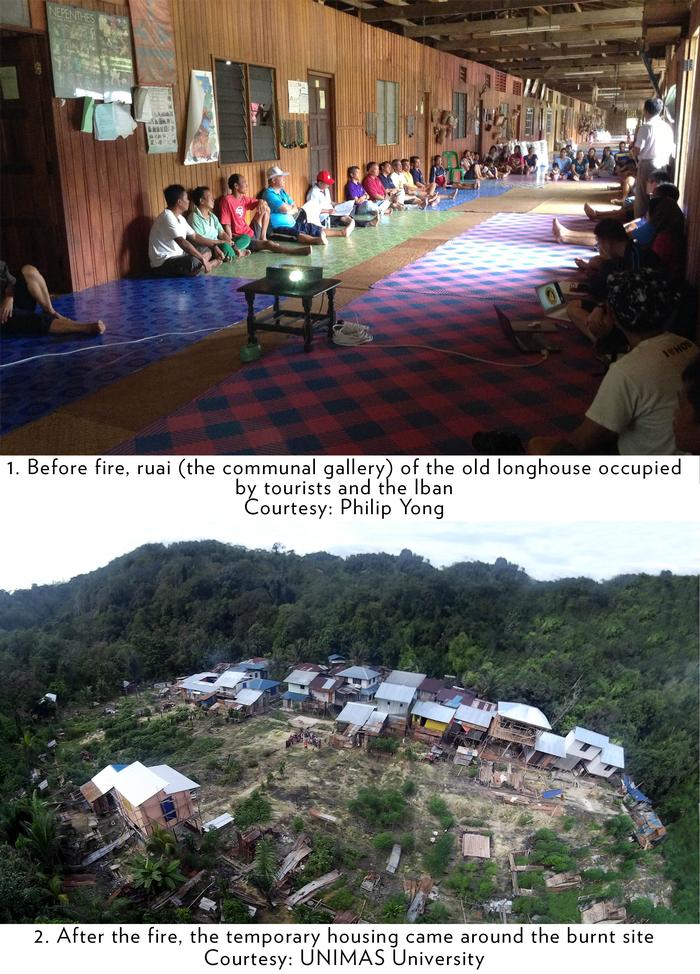

“I stand now at the entrance of the rumah panjai (rumah means house and panjai means long i.e. a longhouse), looking at a line of dwellings, interconnected. The human skull looking down balefully at me through a wicker framework suspended from the rafters, the ruai (communal gallery) seems to stretch a long, long way to the far end. The slatted wooden floor is perched on stilts and the area below, glimpsed between the planks, boasts a clutch of hens and a vociferously crowing cockerel. As I walk further along the gallery, women smile as they carry out their daily chores, a granny flashes me a toothless grin, mothers rock their babies in little bamboo cradles and a small boy, absorbed in whittling a stick, ignores me as he frowns in concentration.”

These statements are from the travel writer Margaret Deefholts, following her 2008 visit to the Nanga Sumpa longhouse. The longhouse is considered to be one of the oldest architectural forms in Sarawak and can be found throughout Borneo Island.

Picture this - as we drive outside the Malaysian city of Kuching towards the Indonesian border, the streets grow bumpy while rolling over hills and through valleys until we face a large lake. A pair of hornbills pass above and we board the longboat and cast off into the water. This lake was once a forest until the hydroelectric dam was built, flooding the forest and creating the lake. We weave through trees of the flooded forest until the lake gradually narrows into a river. The ride becomes rougher over the increasingly rocky rapids. We carry the boat over a small waterfall and push the boat up the river in shallow areas. The jungle is thick now and the sunny day has suddenly turned to a torrential downpour. All of us are laughing at how wet we are after travelling nearly 164 miles for eight hours from the nearby city of Kuching. We arrive at Nanga Sumpa village, meaning “mouth of the river”, a remote village belonging to the former headhunting tribe of Iban people, located in the Sarawak province of Borneo Island in Malaysia, amidst one of the few remaining virgin rainforests. Our first step off the boat is an entrance into an environment of different moods and smells. We walk to where the longhouse used to be.

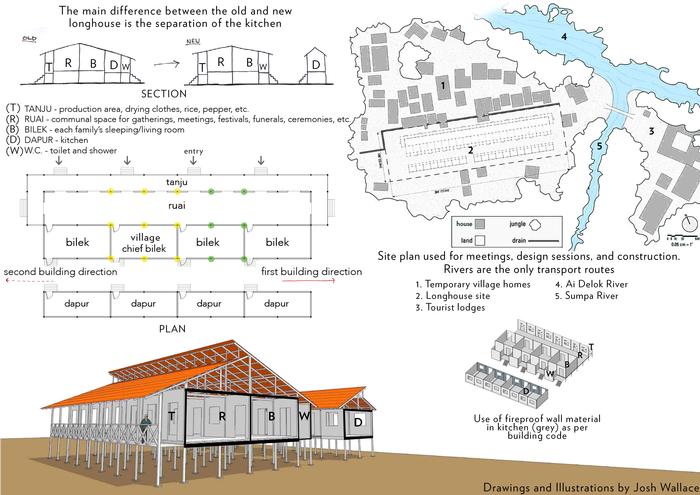

Known as a “village under one roof”, a longhouse is a type of elevated communal dwelling comprising a series of interconnected apartments arranged linearly. Each apartment is connected to a communal gallery space on the side. On the other side of the apartments are kitchens and bathrooms. Longhouses are traditionally constructed of wood with a thatch roof, but more recently many have tin roofs.

Finally, we arrive at the longhouse site. All that is left is a grid of black charred posts, most of them burnt down to the ground. Realizing that most village life had once occurred right where we are standing, sadness fills me. A gathering crowd of laughing young women and men about fifteen yards away interrupt this feeling. Although the longhouse is gone, the people’s vitality was not.

On May 13, 2014, just before the harvest festival of Gawai, a small fire started in the dapur (kitchen) at an unmonitored lit stove. In minutes, the fire began to roar. The flames travelled quickly through the longhouse, growing to a spiralling vortex the size of the communal gallery. Flames erupted out of the longhouse making it appear like a fluttering red bird. Most people managed to get out but two lives were lost and many, injured. The villagers lost almost all their possessions, money, and ancestral heirlooms. Once it was too late to save the longhouse, villagers stood outside in the scorching heat of the flames, watching in horror and amazement as the shelter for more than two-hundred people shrank down to nothing. The Ibans were rendered homeless.

After the fire settled, the smell of charred wood hung in the air. The longhouse was reduced to mangled metal roofing, broken pottery and melted glasswares. People were in grief as they stared at the scorched earth where the longhouse existed. The feeling of loss surrounded them. The body was not there, but the soul existed.

The eco-tourism company Borneo Adventure has been in partnership with the Iban people of Nanga Sumpa village for 28 years, bringing tourists to the village so they may learn about the Iban way of life. The longhouse is located in a very remote area without any cell phone service or internet. When the longhouse caught fire, a Borneo Adventure employee ran to the closest area with cell phone service, a mountain overlooking Indonesia ninety minutes away, to make an emergency call to company headquarters in Kuching. Villagers stayed in the adjacent tourist lodging and Borneo Adventure trips and operations ceased until the local people could recover. The next morning, donated food, clothing, flashlights and other items began to flow into the village.

In the wake of the fire, villagers salvaged what materials they could from the burnt longhouse and began building individual temporary homes. These homes were built around the longhouse site and would serve as places of residence until the new longhouse could be built. Over time however, many temporary homes increased in quality and durability of materials, using concrete, cement-board and timber. This difference in material varies greatly from house to house; some having concrete foundations and walls and others using burnt steel roofing from the old longhouse. Living in individual homes has resulted in a more visible and apparent difference of income between families, a factor which was less visible in the old longhouse.

The jungle air is often quite still and the interiors of the temporary homes can become very hot and stale. The facades of each building have been patterned by the harsh jungle climate, giving each home a distinct appearance against the backdrop of the lush jungle. The ground is very soft and the village can become dusty and muddy. New homes have been built informally, each having a sewage drain leading to the river and a petrol-powered electricity generator, if the family can afford and wants one. The open-to-air sewage drains zigzag under and around the homes to the river, creating an unhygienic environment that risks the spread of disease. The longhouse’s communal gallery (ruai) has been lost, resulting in a loss of communication. This weakens the community, hinders development, and gives no opportunity for greeting guests, an important part of Iban custom. It was decided that building a new longhouse would strengthen village society and community, and also generate income from tourist visits. Moreover, the longhouse is deeply rooted in Iban culture, encompassing many Iban traditions and values in its built form. Rebuilding the longhouse means rebuilding these traditions and values.

In February 2015, Josh Wallace (Josh meaning zest in Hindi), a 23 year old undergraduate of architecture from Canada and still a trainee, was introduced to Philip Yong, a Malaysian-born Chinese man who co-owns and operates Borneo Adventure. When Philip described the story of the longhouse and the need to rebuild, Josh offered to help. Philip asked, “Are you comfortable with staying in the jungle for weeks at a time?”. Desiring challenge and adventure, Josh eagerly replied, "absolutely”.

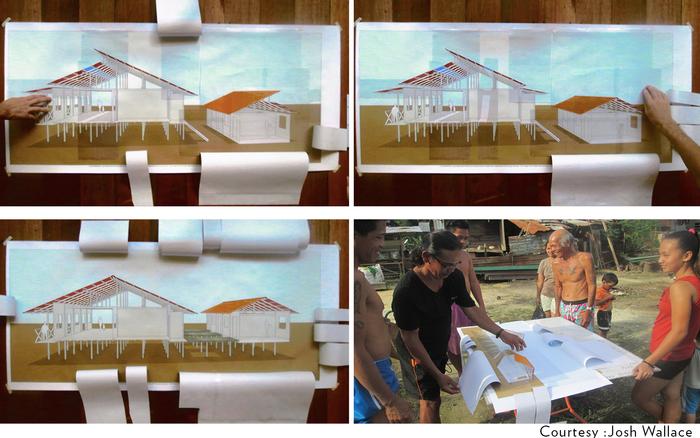

After meeting the Tuai Rumah (the village chief), Josh became aware of the issues the village was facing. The village was divided on which features of the new longhouse design were most important, with competing ideas in relation to fire prevention, ventilation, convenience and tradition. In Josh’s own words, “what is more important, an optimal design made by someone else or the villagers having a sense of ownership over their own design? I decided early that I would not impose any of my values, ideals, or beliefs on their design. My goals were to (1) make tools that generate community discussion, (2) help bring consensus to the longhouse design and (3) produce drawings that aid the construction process.”

In the interest of fire prevention, the village agreed to separate the kitchen from the longhouse. Through extensive discussion and observations, Josh came to learn what design features were not agreed upon. They were (a) a closed or ventilated split roof, (b) ventilated or unventilated walls, (c) skylights, (d) a closed or ventilated kitchen roof, and (e) a raised kitchen with cement bridge or ground-level kitchen.

Generally, longhouse planning involves a verbal design discussion between villagers. This often leads to multiple interpretations of the design due to lack of shared spatial understanding. These multiple interpretations become built form and the intended uniformity is often lost, resulting in lower building performance or rebuilding of certain areas. To better plan the longhouse, Josh makes drawings to help develop a shared spatial understanding between villagers. The village chief and the Longhouse Committee, a group of elderly men, understand architectural drawings (plan, section, elevation), but other villagers are less fluent in these representations. To make the design understandable to everyone in the village, perspective and axonometric drawings are produced allowing for a more inclusive design process. After several attempts, the most effective approach is a “flipbook” of drawings that encompasses all options for the longhouse design. The flipbook, along with other standard drawings, is used in numerous meetings and village-wide discussions. When drawing each option, Josh uses construction details and knowledge that are already in use by the villagers. For instance, the split roof he draws used a detail similar to a tourist building the villagers had built two years earlier, making the option’s execution easier if chosen.

The village chief, the chief carpenter and the Longhouse Committee are Josh’s primary working team and friends. Together they develop a building code to ensure safety and function. The code dictates that (a) the kitchen wall facing the longhouse is made of fireproof material, (b) nothing flammable can be between the kitchen and longhouse, (c) each kitchen’s split roof opens away from the longhouse to control smoke, and (d) all kitchens are connected via walkways for travel when raining.

Eighteen families participate in longhouse construction and inhabitation, each having its own kitchen and bathroom. The longhouse has a traditional closed roof, ventilated walls and skylights. An eighteen-foot gap separates the longhouse and the “long kitchen”. The long kitchen has a ventilated roof that opens away from the longhouse to control smoke. Toilets are connected to a sewage pipe that leads to a septic tank followed by a leach field, a network of perforated pipes that filter waste before it enters the soil.

After going through so much turmoil and uncertainty about the future of their village, construction finally begins in October 2015. The village awoke at 4 a.m. to bless the longhouse site before building. Women play gong music as the men begin raising the first posts in the middle of the building site, making the chief’s apartment. After every post is raised, cheering and clapping fill the air, while women walk through the crowd of builders, splashing water on them and laughing. Once the chief’s section is complete, the next family lay down their posts beside it and attach their section. Each family attaches on to the previous and the longhouse grows in both directions from the chief’s central location to the end of the building site. Each morning begins with a mix of animistic and Christian blessings before building the next family’s section of the frame. The entire village eats together when building the frame, always in a very good mood and in high spirits.

As of now, the frame of the entire longhouse and roof is complete. Each family builds its floor, walls, and ceiling at its own pace. The posts touching the ground are made of Belian wood as it is very resistant to water damage. The Belian posts were donated by Borneo Adventure and the steel roof was donated by a nearby church. Funding comes from the government, Borneo Adventure, and the families, the more prosperous ones donating more in order to create a better living environment for everyone. The longhouse is built formally and the individual homes informally.

Josh’s courage to work in a remote area with rare resources and stunted cooperation is an impelling story. Respecting others ideas, culture, and customs is often more important than designing using only one’s own ideas. When working with a large number of people, coordination is one of the most sought after goals. Using intelligent design tools to make the invisible visible can help people reach consensus. This limits the number of construction mistakes and revisions. Tourists have again, began to pour in. The longhouse now stands as a built symbol of community collaboration, economic revitalization and pride that has conquered homelessness. No longer do feelings of sadness about the village overtake a conversation. The Ibans have regained community, and the new longhouse, its soul.

A good first step in solving homelessness in both rural and urban settings is to take a tour of one’s village or city. This helps in understanding the local knowledge. In a rural setting, I would allow many people to contribute and explore how to create flexible spaces that would be configured by them later. Fundraising can be done by advertising rural culture to the nearby city to encourage tourists to visit the village. We will implement indigenous building methods to minimize cultural shock while exchanging new knowledge to learn new skills. In the beginning, volunteers will assist making these shelters.

In a city, I am very interested in how a place can act as a shelter and as a possible place of work. To save time and energy, uninhabited warehouses and factories can be converted into rentable shelters rather than making new ones. To encourage collaboration, different kinds of people will work under one roof, exchanging knowledge and skills while building a small-scale economy. As former homeless people move up in class and out of the shelter, others will take their place. This model is based on sustainable temporary ownership.

As an individual, I can start an NGO to initiate collaboration between the homeless and businesses that have a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). This creates an opportunity for the lower class to build skills and become employed. People who were once homeless can develop a sense of purpose and begin to contribute to society, curbing the amount of resources needed to support them.

This initiative aims to help create a sense of ownership and purpose in homeless people. Both "agreement" and "disagreement" can become built form, further crystallizing a society’s triumphs and failures. I do believe that participatory design techniques can provide a platform for discussion, negotiation, compromise and ultimately agreement on the issue of homelessness.

The author would like to acknowledge Josh Wallace for his assistance in making this submission.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |