[ID:1347] The Art of Confronting Poverty: Architecture by the PeopleIndonesia The roaring sounds of heavy building equipment and the rowdy honking horn of cars and motorcycles are tangled, cranes are standing tall on every corner of the city, the development of the Yogyakarta city, Indonesia, are monstrous than ever this late years, turning the city into another concrete jungle, separating the upper class and below middle into a further level. In the other side, water are streaming slowly in three main rivers of this city, the infamous Code River on the center, Winongo River on the west side and Gadjah Wong River on the east side. As the Nile for the Egyptian and Gangga for the Indian, these rivers in Yogyakarta used to be the soul of the city where the life of the society begin.

As veins for a body, the river held a crucial function on earth, not only for the people that lives from it but also for the environment and the biodiversity of its flora and fauna. River as an ecological treasure for the city is needed to be guarded from all forms of excessive exploitation and pollution. At one time these understandings of a river were fully considered by the government followed by the publishing of a National Law mentioning a demarcation of a river, a requirement of distance from river and its closest building, an effort to protect the river function.

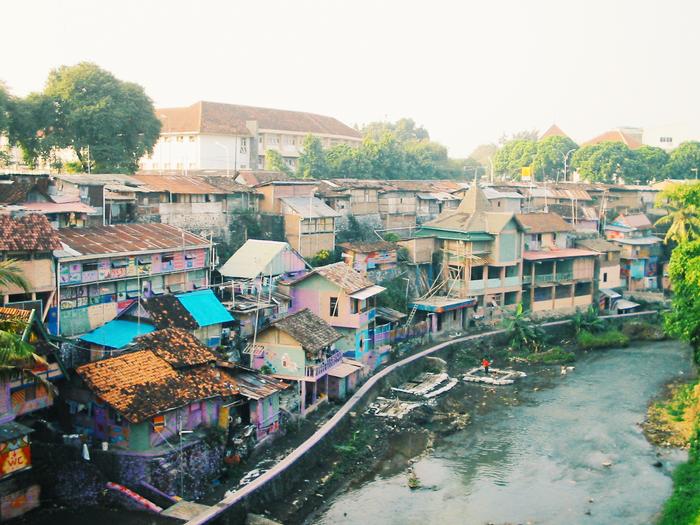

Year by year, decade by decade, the development of this city got faster and the growth of the city became uncontrollable, problems by problems were coming in turn and the commitment to protect the river was slowly vanished. As the city became denser, the illegal land became an alternative for the below middle class urban society. The limitation of access throughout a descent settlement forced these class of society to sneak upon the cheap and abandoned land in the skirt of the city including the illegal land such as the riverside. The status quo depicted how these rivers are forced to tolerate the sporadically growth of the illegal settlement, how it turns from a precious element into a slum, a symbol of marginality, seen as a latent problem, often left as an unfinished business.

As the river had seriously losing its main function, twenty years ago government were planning a massive eviction towards these river society, begin from the Code River and chaos happened as the society claimed that they had fulfilled their duty as a citizen by paying a continuous electricity bill and land taxes. The riverside society were demonstrating as the issue gets real, both of the government and the society are head to head claiming rights, one claim as the sake of the river’s function and the other tried to firm their feet on the riverside they called home. The condition were complex and tense until one man stands within the river society and changed the history.

That man was Romo YB Mangunwijaya, a pastor, a socialist, a writer, a practicing architect and a lecturer. He spent eight years from the late 80s to intensively mingle with the society of Code River settlement that once populated with the destitute such as scavengers and prostitutes or even criminals, who lives in the land illegally below secondhand plastics and cartons hut. As he believe that an environment is a reflection of the people, his vision was to humanize and uplift the degree of this society that singularly will uplift the condition of the river.

Romo Mangun was provoking a different idea that time, offering a new methodology of people approach and to understand the relationship between people and their habitat, to leave his knowledge and mastery of architecture behind and to put the need of the people as the priority. On his hand, Code River settlement was transformed into an organic neighborhood with a colorful semi vertical house with beautiful murals and a simple tectonic structure that is very practical and economic friendly. Together with the people Romo Mangun helped vanish the image of slum, rearrange the neighborhood and built descent houses with affordable materials which not only transforms the environment but also the life of the people, which won him an Aga Khan Award in 1992.

A decade after the Romo passed away, the story of him and Kampung Code continues to inspire many people yet ironically 80% of the poor still live along the riverside and retains as a complex matter for this city, leaving me with an open question on how could the success of the story stop to continue, how could with a success precedents the image of the riverside in this city has not changed dramatically, what happened along the decade and why the fight against poverty in the riverside was vanished. Upon these questions I’m finding myself walking along narrow pathway beside the Winongo River into a small neighborhood where a group of young architects are arranging a monthly meeting for the riverside society. On a humble space these architects were explaining a project like I haven’t seen before, to the grass root community, to the people who didn’t get used to a design project, patiently, with a very simple words and simple figures. Conversation happened, feedback are given both way, a learning process is happened.

Called themselves as Arsitek Komunitas or Arkom, these group of young architects had been working with the grass root society since 2009. Taking Romo Mangun as one of their inspiration, Arkom also have the same goal to raise the dignity of the marginal people through architecture. Slowly but sure they started some small projects to begin the movement of Kampung Restoration where they helped the neighborhood beside the river to arrange their own home and in the end to uplift their living condition and make the river a better neighborhood, a better environment for all.

On the other afternoon, Ms. Anna, one of the architect from Arkom accompanied me to visit one of their early project on Ledok Pakuncen, a small neighborhood resides along the Winongo River. As we walked down on a small alley into the Winongo River, people of Ledok Pakuncen greeted Ms. Anna as she is a no stranger to the neighborhood. Between narrow alleys and small parcels of humble houses, there were a lot of activities happened in this neighborhood of 54 families, people are friendly, children are playing badminton, women are gathering for a monthly meeting mothers are taking their child for an afternoon walk, some of them bath their child in front of the house, someone else sells traditional chicken satay while the others are cleaning their house.

In the middle of the neighborhood, a unique bamboo structure is standing still above the city sewage. Balai Warga – a resident’s hall – of Ledok Pakuncen are the center of every activity in the neighborhood, from a regular meeting of the residents until a wedding ceremony are often held in this space. Spanned over 2,5 x 7 meter, the Balai Warga was beautifully designed with a tectonic technic that shown all of its structure and made by a specially-treated bamboo. Television was latched in the wall of the hall along with several hanging plants placed in a recycle plastic bottle, but among all the furniture my eyes were most fascinated by some photographs hung in this modest hall, all of them shown happiness and smiles from the residents. Those are photos captured the process of making the resident hall, shares knowledge between building experts and the society, men were constructing the bamboo, women were mixing cements for the hall’s foundation and children helped to bring some of the bamboo to work on. One residents I asked was still remember those days, two years ago, night and day, weekdays and weekends, the residents were all together tried to make their dream of a place to gather together to be real by working hard on this project. Shifts were made due to the different time of work of the residents, some people worked at night and some people worked at the day and many of them ever skipped some days work to complete this project. She said everybody was taking a big part in making this project, but the most part she was appreciating the women and men behind the design, behind the start of this project, the architects, Arkom.

The road to these architects’s vision was nothing but up and down, every society have their different manner and characteristic which make it hard to estimate the time and methodology used. For Ledok Pakuncen their first approach was so simple, to come and try to get friendly with the society, continuously build trust with the people for four months. The next step was the mapping process. Through this process, Arkom assisted the society to gather the neighborhood information and form it into a complete package of map as well as to identify its problem. In the end, the results are numbers of necessity priorities, and in the case of Ledok Pakuncen, it is the resident hall.

In the other hand, every realization of architecture idea will need a funding. In a modern days, to build skyscrapers one will need to estimate costs for the architect to design, contractor to plan the system, workers to build the building and another for the materials. But these humble houses on Ledok Pakuncen were built firmly even if they live below the line of poverty. To work together is the answer. Arkom as the facilitator for this project arranged a system for savings, they gave a small stimulus amount of fund to start the project and the rest are collected by a 20 cents saving for every household every day. By the end of the time they managed to gather enough funding and use recycled material to build their dream hall.

At the end of the time as I leave Ledok Pakuncen, this unique bamboo structure looked so much more than a space for me, it is not just a small scale architecture project, not just a shelter made of a recycled materials, it is a prove of people power, that with working together we can break the limitation of poverty and have a better living. The process might be slow and hard but at the end the society is happy and they feel proud about what have they done. When they looked at the resident’s hall they will feel the sense of belonging to their neighborhood, to encourage them protect their own land, their river.

The story of Ledok Pakuncen might not be as legendary as Romo Mangun’s Code River but as I seek a silver lining between Romo Mangun and Arkom I found an interesting term: start small, start slow. Romo Mangun was not coming to the Code River in all sudden and build as well as Arkom, both of these architects invested on time used for socializing, on the society opinion, and the most important is they both believe the power of the people, that more hands means more. That as an educated architect we still need to listen, put our mastery behind and focus on the necessity.

By starting this small projects, Arkom had continued this method into another five neighborhood. As I tried to answer the previous question on the paused progress of Kali Code, there are a different in between the two project, Arkom fully understand that a grass root development is a continuous one, they form a community called Kalijawi to accommodate society in Gadjah Wong and Winongo River to continue the learning process. These projects had been noticed and appreciated by neighbors, societies, recognized by the local and international media and often used as a meeting points for a meeting or an international workshop. Yet in the other hand, some people disagree, arguing that this resident’s hall will justified these people to live in the land illegally which is against the law. Some others sees eviction as a way out and that the riverside society should be moved into vertical housing and free the land on riverside as a public facility for the citizen. In the other hand the river society itself has prejudiced the housing as a bad terror and that most of them refuse to live there. Among all the pros and the contras, these architects were placing themselves as a mediator to find the line between, slowly implement the value of hygiene, waste management and river protection to this people yet in the end Arkom considered that somehow the society need to be moved by giving them an understanding.

In the other side, government as an accommodator of communities tried to preserve the river as well but in a different way, they also formed a community called FKWA or Forum Kali Winongo Asri, similar with Arkom. FKWA is concerned about the preservation of the river itself while Arkom and its Kalijawi worked more on the settlement. The government has been highly appreciate every project done by Arkom but in the other hand they have not had any initiation, it is in the hand of the people whether they want to move forward or not.

Today there are still a lot of questions floated on the society on whether this small scale project is enough to solve the poverty problem in the neighborhood, and the answer is no. There are a lot more to do to solve and end the poverty problem yet the small resident’s hall could not solve it. It will need more time to solve it with more ideas and more hand to work with. In the end, anyone could write a thick book of problems of the riverside in Yogyakarta and listing problems from the waste management on the settlement up till the questionable health of people. It is truly naïve to say that a small resident’s hall such as this Balai Warga in Ledok Pakuncen will immediately solve the poverty problem. Obviously a small architecture project would not going to solve that. Both of the welfare rate or income of the people have not significantly arose. But what’s essential is the attitude and the view of the people that has been uplifted by the existence of this project. The society have felt more pride and care towards their neighborhood. The project is not about just to make the neighborhood to have an icon, not just that it looks nicer with the resident’s hall but it’s also that they finally feel that dream could be realized and if they worked together the dream is easier to achieve and that it is possible for them to make their life better by their own work.

In the end, the question of the ability of architecture as a way to reach a better life is not just a yes or no quest. It is a complex one. As an architect what we can possibly do is to be a trigger for a change. Spark a new ideas to inspire people. Creating an art to empower a movement of the people.

If you would like to contact this author, please send a request to info@berkeleyprize.org. |