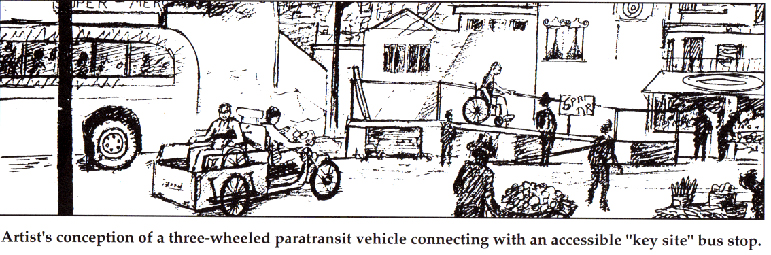

Eve EdelsteinFIRST SEMESTER REPORTEve Edelstein, M.Arch, PhD (Neurosci), EDAC, Assoc.AIA, F-AAA Expanding the Universe of Design: Applying a Neuro-Architectural Process to Create Accessible Cities‘Neuro-Universal’ Design An innovative curriculum, based upon iterative interaction among architecture students, educators and academics, combined specialist expertise and experience in enhancing design for individuals with a continuum of abilities. Based upon iterative interaction among architecture students and faculty, disability resource educators, and individuals with disabilities, a‘ Neuro-Architectural’ approach informed design pedagogy to address and expand Universal Design outcomes, embracing concepts about the influence of design on brain, body, and behavior. This approach integrated the emerging fields combining neuroscience, architecture and research-based design’, along with universal design objectives. In training design students in the scientific method, critical analysis and design research, students are challenged to expand their perspectives to include the design of spaces that serve both health and wellbeing, and to translate evidence from a broader range of disciplines, beyond a narrow ‘universe of design.’ Process A pragmatic approach for students and faculty addressed the clarion call by architects and their clients for rigorous and trustworthy data to support design decisions. A novel process, integrated neuro-architectural concepts with universal design principles, demonstrating how to ‘put the evidence’ in evidence-based design. A conceptual framework based upon the philosophy of science linked 1) the physical parameters of the built environment as ‘input’, 2) the brain, mind, body and behavior as ‘responses’, and 3) universal design objectives as measures of ‘outcome’. Each of these primary categories (input-response-outcome) was divided into sub-categories in a grid that prompted comparison of the interactions between each design option, competing objectives and predicted outcomes. Such interactions can be used to prioritize outcomes in terms of the many users, and the myriad of uses, that each built project must address. Finally, design solutions addressing these outcomes may be ranked relative to the client’s institutional, economic and ecological goals, and translated into design principles to inform design features for the individual, group, public, and social contexts. This ‘Input-Response-Output’ design priority grid, helped students to cross-check each physical attribute of design against its impact on the brain, mind, body, and behavior. Student Performance and Learning Objectives Student performance and learning objectives were developed in discussion amongst the design faculty and administration of the School of Architecture at the College of Architecture, Planning + Landscape Architecture at the University of Arizona, Tucson. For administrative reasons, the ‘Neuro-Universal’ team was asked to collaborate with an existing design studio sequence focused on Techtonics (Fall Semester) and Land Ethics (Spring Semester), starting with sixty-eight undergraduates as part of a 3rd year Bachelor of Architecture NAAB accredited degree program. This presented a challenge that required integration of student learning objectives and performance criteria at conceptual extremes, as human-centered issues are typically taught in a different year. In order to meet the student performance criteria (SPC) objectives already assigned for this cohort, neuro-universal learning objectives were added to syllabi, with no reduction or adjustment to tectonic or land ethics assignments. Collaboration with the Co-Director of the Interwork Institute, College of Education at San Diego State University incorporated approaches previously developed and taught at the NewSchool of Architecture & Design. This curriculum introduced universal design concepts to students enrolled in environmental architecture course, and focused on design projects including 1) an educational institution to serve students and faculty with a broad variety of cognitive and physical needs, and 2) accessible residential design for a real-world client with multiple sclerosis. The syllabus included several parallel processes, including critical analysis of clinical research, and translation of these findings into design principles. A follow-up student survey and the analysis of features incorporated in student designs revealed their appreciation for authentic learning experiences and an increased desire to enhance design outcomes for all abilities. The faculty team was further enriched by integration of a team of experts from the Disability Resource Center at the University of Arizona, along with faculty and students who offered personal and professional perspectives from individuals with disabilities who used a variety of assistive technologies for mobility, navigation, environmental controls, and cognitive performance. Value of engagement of diverse users and collaborators Experts and users collaborating with the UA BERKELEY PRIZE team offered a breadth of perspectives from faculties and professionals representing 1) design and architecture, 2) bio-psycho-social research-based design, and 3) environmental equity. Discussions centered on neuro-architectural concepts and processes around equity of use, asking students to think about their own sensory, cognitive, and physical experiences, and then to expand their thinking to consider the experiences of a range of ‘users and uses’. Discussion considered the continuum of human ‘users’ and the dynamically changing ‘uses’ that reflect an individual’s experiences throughout their daily lives. Consideration of each individual’s physical, mental and clinical and cultural status, as well as interaction in urban, built and natural settings provided a framework for students think about their own interactions, abilities, and experience of design. Lectures by the DRC and invited speakers also discussed the philosophy and impact of equitable design. The concept that architecture can and should ‘flex’ to meet the continuum of human needs, rather than require that people ‘bend’ to built settings, challenged students, faculty and specialists to think creatively about design priorities. Involvement by experts and users Students and faculty were honored by the opportunity to engage with faculty and students at the University California, Berkeley, and the Ed Roberts Center. Sixty-three students and 8 faculty from CAPLA participated in Christopher Downey’s course on accessible and universal design, Bill Leddy’s architectural tour of the Ed Roberts Center, and in conversations with Ray Lifchez and specialists at the Center for Independent Living. Literature and links to resources provided by the Berkeley Prize Committee, along with publications and presentations by the neuro-universal faculty were posted on the student course site for design faculty and students. Together, the UA design faculty, specialists in disability resources, and students toured sites selected for their design studio projects, discussing access and to and experience of a number of sites within the urban context of San Francisco. The disability resource faculty attended studios, mid-term and final juries, providing iterative feedback and insights to inspire equitable design, prompting students to consider the balance required of design for social equity. The interplay between design concepts, program priorities, accessible requirements and the imperative to consider all peoples was discussed. Achievements Impact on students’ design process Students completed two projects in the Fall 2012 semester. Project 1 considered design of a transportation hub in downtown Tucson. Project 2 required that students create a multi-story tower in downtown San Francisco in the Embarcadero district. Site visits with DRC and SDSU staff yielded valuable opportunity for individual and group discussions about the challenges posed in an urban context. Students were asked to generate design hypotheses, and use neuro-architectural grid analyses to drive their design thinking. ‘Neuro-universal’ learning objectives focused on interpretation and translation of information about sensory, perceptual, physical, and phenomenological responses to design. The students presented their conceptual framework, inquiry process, and design solutions to the faculty, students, and disability resource specialists in studio round-tables, conversations and juried reviews. Impact students’ mid-term and final projects Mid-term assignments requested that students articulate design hypotheses and neuro-architectural grid analyses, revealing sophisticated design thinking from several students. Several design visualizations and models demonstrated sophisticated consideration of equitable design. Examples include the choreography of equitable entry points, interaction places, and circulation paths that consider physical movement, auditory and visual responses to design of a downtown trolley station. Other examples demonstrated understanding of design for those with a variety of sensory, perceptual, and physical interactions with design. Changes in student attitudes In order to assess prevailing changes in attitudes as a result of interaction with universal design concepts, students participated in group discussions and formal surveys. Surveys of student attitudes and learning outcomes explored their appreciation for authentic learning experiences and interaction with faculty and peoples with disabilities. Analysis of these surveys will consolidate findings, and be developed to probe for further insights. The students expressed great appreciation and knowledge gained from meetings and site tours with Chris Downey and his students, Ray LIfchez, and Bill Liddy at the Ed Roberts Center. Students also found the neuro-architectural process and interactions with users and experts useful. The neuro-architectural process and visits to Berkeley helped me to .... ”think about what my design is going to offer in terms of what to see, what to smell, hear, and what to feel.” Changes in design faculty attitudes “Involving user/experts is invaluable.” “Increasing the number of sessions that were interactive in nature would be helpful.” “Having raised consciousness in this area, it will be passed on to future students.” However, being charged to focus on previously designated student performance criteria, the faculty did not make great changes to their studio approach, but did collaborate with disability resource experts in an attempt to bring them into an existing studio framework. This interaction with user/experts helped faculty to “understand the complexity of the situation beyond basic codes etc.” A valuable lesson was realizing that this content is not “just an add-on”. A greater “commitment upfront from the administration to waive other studio criteria – to make it is more of a focus” would be helpful. “This was acknowledged at the end of the semester, and there was consideration that some existing criteria should have been lessened in order to facilitate integration of this curriculum in an easier way for faculty and students.” “Even though it should be an inherent part of the design process, there needs to be a commitment beyond the superficial, … as it is not a simple issue for students to come to turns with as an additional check box item.”

Other faculty members offer: “There has been some shifting in my perception of the issues facing the visually impaired and I see that this population could be well served by a creative inquiry by architects into various methods of serving their unique needs. Also, having opened the doors last semester in a discussion or two to the behavioral and psychological challenges that exist between the those individuals who live with significant physical challenges and those of us who operate with far fewer challenges, I can say that I have begun to more fully understand the importance of UD from this human behavioral perspective and how critical it is to remove the barriers that create, not only physical difficulty but perhaps even more significantly, emotional difficulty as those who are challenged struggle to simply lives their lives WITHOUT the ubiquitous perception of those who perceive them to be challenged.”

Challenges Our challenge has been in part logistic. The integration of additional content in a densely packed syllabus that addresses specific student performance criteria imposed limitations. Upon reflection, it would be preferable to integrate neuro-universal content in studios focused on human factors criteria. However, every architectural project must consider human interaction in the functional program. Therefore, the neuro-architectural process and universal design concepts are appropriate for all projects and within every studio project. If architecture may be defined as the application of design in habitats for human interaction, then it can be argued that every studio and student project, must teach and take into account the continuum of human needs. Proposal for the Spring Semester The way architects address the needs of a diverse society will change most rapidly if we synchronously address the attitudes of the current generation of professionals, scholars, and teachers along with their students. In order to achieve greatest progress, knowledge building among the faculty, both designer and user/experts should engage in deeper understanding of the complexity of each other processes. While some resource experts in our group had a great deal of experience in studio pedagogy, several were unfamiliar to the design process. Similarly, some of the design faculty had limited experience teaching human-centered curriculum. Given these insights, we continue to discuss new options for the Spring Semester in order to achieve greatest success.

Additional Help and InformationAre you in need of assistance? Please email info@berkeleyprize.org. |

|